[Images by BUILD LLC]

There’s an important shift happening right now in residential architecture and we’re encountering it not only with the residences we design for clients, but also in our explorations with the Case Study House series. It’s a psychological evolution as well as a physical lifestyle shift and it has the potential of significantly improving people’s lifestyles as well as making a profound impact on our built-environment. This shift is bringing the older generation, those 65 years and up, back into the family household. It’s a critical time for urban areas to consider this social shift as jurisdictions vacillate between supporting density or preserving small town nostalgia. It’s also an important shift globally, as worldwide anxieties continue to focus on sustainability, fuel consumption, and the blight of the automobile. The relevance works its way down to the level of the family unit, providing the possibility of deepened connectedness between grandparents, parents, and children. Everybody wins if we’re open to and mindful of making the shift. To break it down, here are five reasons we support multi-generational living, with some examples and a few floor plans:

Our psychologies are geared for multi-generational living.

It wasn’t until the 1930’s and 1940’s that families in the United States began to disseminate. Until then, it was common for several generations to share their lives as well as their living spaces. According to the Pew Research Center, by the 1980’s only 17% of those aged 65 and older in the U.S. lived in a multi-generational family household, down from 57% in 1900. It has only been in the last 75 years that our culture has moved from multi-generational living to a single family living. While the gap has spanned several generations now, we don’t need a study to recognize that our brains and social constructs are still deeply influenced by multi-generational lifestyles.

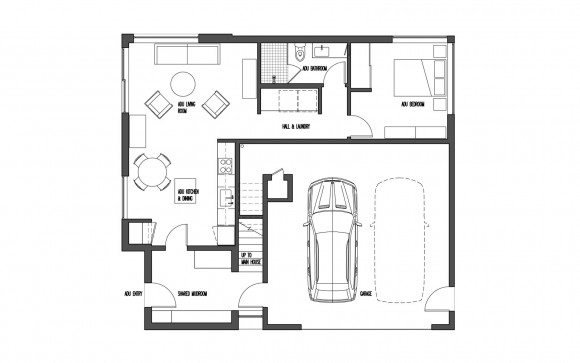

Seattle, despite its hesitation to embrace true density, allows single family residential lots of certain sizes to include an Accessory Dwelling Unit (ADU) within the home or a Detached Accessory Dwelling Unit (DADU) in the backyard. These provisions are key players in multigenerational living and we’re putting them to the test in our Case Study House 2016 (CSH2016). The 3-level residence includes a 700 sf ADU on the ground level, a true mother-in-law unit with all the amenities of a condominium. Establishing an independent living unit in the structure not only adds much needed density to one of Seattle’s north neighborhoods, but brings the lifestyle back to how families have functioned for the most of history.

It gives us all more quality family time.

Multi-generational living promotes stronger connections between families, allowing grandparents and grandchildren to establish relationships which have previously been limited by the all too common holiday travel schedule. Children have an extra set of adult role models, parents get a live-in baby sitter for a few extra date nights, and grandparents are reconnected with the full resources of a family unit.

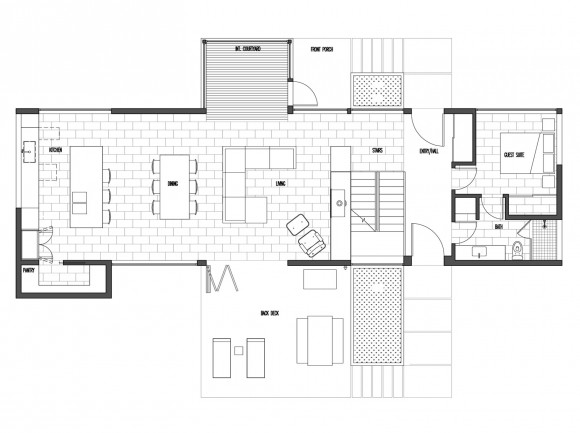

It’s important to understand some of the nuances of multi-generational living, namely that it doesn’t always involve older family members living full-time within the home. We’re regularly involved in the design of many homes for clients whose cultures place an importance on hosting visiting parents for extended periods (months at a time). In these situations, an area of the home should be dedicated to their stay by offering the privacy required of their lifestyle. This typically involves designed separation of the guest suite from the main house, an en suite bathroom and sometimes a kitchenette. The Harrison Street Residence, below, includes guest quarters specifically designed for visiting grandparents and uses the main entrance hallway to separate the guest suite from the common areas of the house. Grandparents can come and go as they please without disrupting the family, but at the same time, they are part of the family dynamics.

It builds and sustains community.

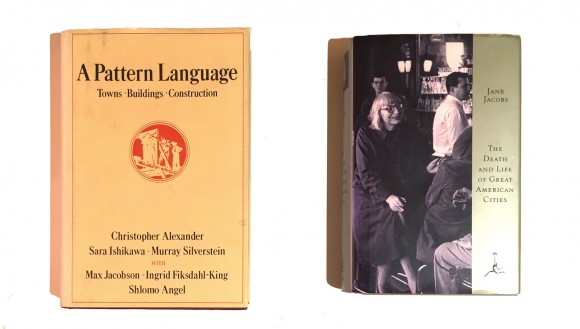

Urban planners and architects alike are well acquainted with Christopher Alexander’s 1977 book A Pattern Language which dedicates one of its 252 essential patterns to “old people everywhere.” Outlined in the text is the growing rift between the young and old simply due to the popularity of retirement communities, where older generations are essentially segregated from society. Likewise, younger generations are deprived of the wisdom and culture that make for a rich and layered life. Pattern #40 of the text states, “Clearly, old people cannot be integrated socially as in traditional cultures unless they are first integrated physically …”

Alexander’s beliefs on multi-generational living dovetail nicely with Jane Jacobs’ 1961 masterwork on city planning, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. She describes the importance of “eyes on the street” and cites older generations as having the time and patience throughout the day to act as the guardians of their neighborhoods.

The additional costs are nominal.

We like to say that the first square foot is the most expensive square foot on a project. Simply due to the economy of scale, each square foot after that is a little bit cheaper. The concept applies very well to adding a ADU to a single family residence. The excavator is already on site, the framers are already tilting up walls, and the siders are setting up their jigs whether an ADU is being added or not. Factor in that the land and utility costs have already been absorbed, and the costs of adding a living unit are nominal compared to the added value.

Concerns about vertical circulation with multi-generational living units are well-founded. Multi-generational residences that include multiple floors need to consider design strategies for individuals with varying degrees of mobility. Clients are often surprised at the practicality and cost-effectiveness of residential elevators which start around $30k installed. In addition to residential passenger elevators, we’ve also installed a few dumbwaiters which can assist with moving things around the house—a huge help in multi-generational living.

It contributes to sensible sustainability.

In many situations, there is an enormous amount of fuel (and dollars) saved by families traversing stairs rather than jet streams and highways en route to visit each other throughout the year. The footprint of residences combined with ADUs has a lesser impact when compared with separate living units on their own parcels of land. There are also efficiencies with the shared utilities as an ADU attached to a single family residence takes less energy to heat than if it were a stand alone DADU.

While multi-generational living may not be the perfect solution for every family, we’re seeing the ideas mentioned above become more prominent in residential design. Our Case Study House series tackles the issue head on and we’ll be covering the CSH2016 ADU throughout construction to completion. Stay tuned.

Cheers from Team BUILD (and the rest of the family)