[All images by BUILD LLC]

If you follow BUILD on Twitter or Instagram, you’ve had a sneak peek at some fresh images of our latest project. We haven’t written much about it yet, and today’s post will take a deeper dive into our Case Study House 2016 design along with what we’re learning from the Case Study House series. We’ll also review some of the new challenges and opportunities of designing and building cost-effective modernism in the city.

As another BUILD family grows up, it’s time to move on from the Park Modern multi-family development, and into a single family home. The move also provides an opportunity for multi-generational living with an accessory dwelling unit, which we’ll cover in greater detail on a future post.

At the moment, finding land in Seattle is becoming a serious challenge. However, off-market opportunities still exist, despite the highly competitive real estate market, which is how we secured a small urban lot in the Tangletown neighborhood just south of Green Lake. The neighborhood has a sense of community and is walking distance to several urban amenities such as coffee shops, restaurants, and local bars, in addition to Green Lake Park. The mixture of houses from different eras and built in a variety of architectural styles helps the case for the introduction of a new modern house.

One of the most important aspects of our Case Study House series is the approach. We design these houses for ourselves just like we design for our clients. Taking our own medicine offers us insight on what it’s like to be in a client’s shoes while helping to refine our design process. It allows us the opportunity to test new methods and materials that are not ready to enlist clients in yet.

As with all of our projects, the initial phase takes a rather scientific approach of researching and gathering information. This information is then organized, translated, and diagrammed to communicate key circumstances and ideas. These circumstances and ideas start to inform the function of the architecture and form starts to take shape, which we refer to as what the building is doing. Once the architecture is functioning as it should and a preliminary massing has been established, the poetics of the design can be addressed.

The research and gathering process has been particularly insightful with the Case Study House series and we’re noticing important circumstances that apply to most urban singe family residences. We’ve organized our observations into 5 significant patterns along with our Case Study House strategies to deal with them:

Compact Allowable Building Areas

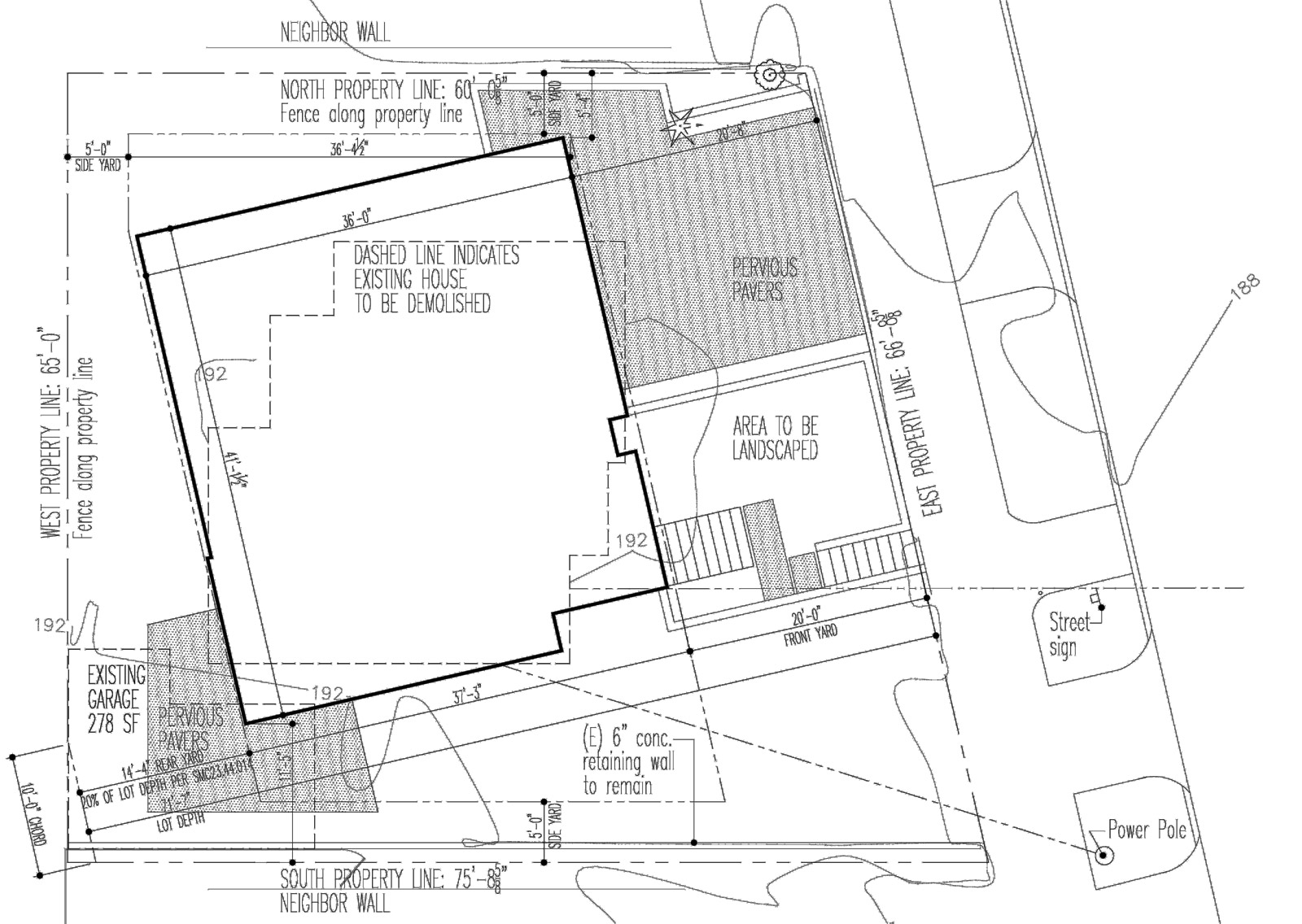

Most urban lots that are available in the current market are limited in area. By the time you account for setbacks, easements, and other limiting factors, the buildable area is quite restricted. We’ve found that 35 to 40 feet is the magic range for the minimum dimension of buildable area in both width and depth. This allows for a functional program within interior spaces, while fitting into the restrictions of many of the properties we’ve encountered. The CSH2016 is a snug 41’ wide x 36’ deep and fits just inside the setbacks.

Views Require Strategy

With the increasing density of most cities and the limited availability of lots, a nice view of the city, mountains, or water is becoming increasingly difficult to attain. At the same time, if view potential exists (no matter how small) it’s almost irresponsible to pass it up. The compact house footprint as described above allows the structure to go up rather than out. By placing the common areas on top and adding a roof deck, any possible view is optimized. We’re following this formula with the CSH 2016 and, in addition to maximizing natural light, the roof deck will grab a bit of Green Lake view.

Stormwater Management Thresholds

Jurisdictions in the Pacific Northwest have almost uniformly adopted building codes aimed at reducing storm water runoff or establishing requirements to temporarily keep storm water on site. Without an awareness of these thresholds, a design can easily trigger complicated and longer permit review timelines (in addition to expensive storm water retention systems on site). In the city of Seattle, that critical threshold is 1,500 square feet of impervious surface area. Exceeding this amount requires storm water mitigation and additional permit reviews by the building department. The CSH 2016 stays just under the threshold by keeping to a tidy footprint and specifying pervious pavers at areas like the driveway.

Navigating the Lengthy Review Process

With the design and construction industries operating at full throttle, building departments are swamped. Simply getting a permit intake date in Seattle is a reservation made 3 months in advance, after which the 3-4 month permit review begins. In order to condense the design and permitting timeline for the CSH 2016, we filed appropriate paperwork to establish the permit intake appointment the moment land was secured. Special permit reviews like the storm water management, mentioned above, further add time, complexity and cost to the permitting process. A primary focus of the Case Study House series is to decode the permitting process and develop methods to streamline it.

Allowing New and Old to Coexist

A common situation we’ve found is the older house nestled within a neighborhood that, while it has served its purpose well for the past century, now finds itself at the end of its functional life. The land is desirable, the structure is typically devalued (and too small for a family to comfortably reside), therefore making the property financially viable as a tear-down. The circumstances of this opportunity, however, involve neighborhoods populated with traditional homes that may have been renovated or remodeled, but still maintain a deep sense of nostalgia. It’s a delicate but common challenge for architects and homeowners with a modern design philosophy. The CSH 2016 is located in a cozy neighborhood surrounded by a handful of beautiful turn-of-the-century craftsman style homes as well as a few modern examples. To us, good modernism is simply the use of materials and methods of the current era. The authentic and old can coexist just fine with the authentic and new. Good modernism respects the traditional by neither copying it nor getting in the way of it.

That’s our quick look at the circumstances we’re designing for with the Case Study House 2016 and the continuing patterns that we’re seeing more often with urban residential design. A roster of CSH 2016 blog posts is currently being developed, and we look forward to sharing more on the behind-the-scenes design strategy. Stay tuned.

Cheers from Team BUILD