[All photos by BUILD LLC]

Sustainable design is a hot topic these days, and, for the most part, we are encouraged by the thoughtful effort many are putting forth. Along with the popularity of sustainability in the built environment (or “green design” as it’s so often referred to) comes an array of interpretations. Many of these interpretations are producing valuable applications in design and construction, creating solutions which significantly reduce energy consumption, limit waste and increase durability. These are the solutions that, when adopted by enough professionals, will increase the quality and lifespan of the built-environment while taking responsibility for the health of the natural environment.

Along with popularity though, come other, more dubious interpretations of sustainability. These interpretations routinely give sustainability an air of glamour and privilege. We notice this pattern at dinner parties (where people talk about sustainability with a certain panache), within design award ceremonies (where “green design” is commonly given its own submission category), or in the marketplace (where there’s no shortage of praise for that sexy new “eco” house gadget). There’s an unusual degree of polish and exclusivity around this paradigm. The real risk is that it becomes a smug art form if guided by these forces, or worse: a secondary green-washing movement.

Such interpretations strike us as a bit of a spectacle primarily because sustainability has always been a matter of practicality and modesty here at BUILD. Good sustainable design should be unassuming and down to earth. To us, the most sustainable solutions disappear within the home and do their job quietly and cost-effectively. Sustainability shouldn’t be about high-gloss marketing, narratives for entertainment affect, or gadgetry for gadget’s sake. It should be about real solutions to ensure a high quality of life for future generations.

Years ago we developed a sustainability statement to clarify our interpretation of sustainability into five simple tenets. We think this sustainability statement is as pertinent today as ever (maybe even more so given the prominence of suspicious interpretations that cloud the true objective). Far from glamorous, these tenets do not employ some cool, novel device to install on your roof and they aren’t exciting to drop into conversation at cocktail parties. Instead, they are five sensible and practical real-world methods of sustainable design and construction. They are fundamental and instinctual; some of them are basic to the point of being primal. We’ve been working on them for decades in the office and out in the field and, in our opinion, they are the real deal. We’ve translated them into a real-world application of sustainability, each of which has recently been implemented on one of our job-sites, in a simple, meaningful way.

Durability. Make sure stuff works and is built for future generations. Outsmart and outlast both designed and perceived obsolescence.

We live in odd times. Everything from our mobile phones to the clothing we wear is actually designed to be superseded at some point –in fact, consumerism now depends on it. As architects, we’d like to think that we have a higher calling to practice design methods that challenge and out-maneuver obsolescence. Durable design should not only imply resilient materials, but should address changing family dynamics and functional relevancy in the future.

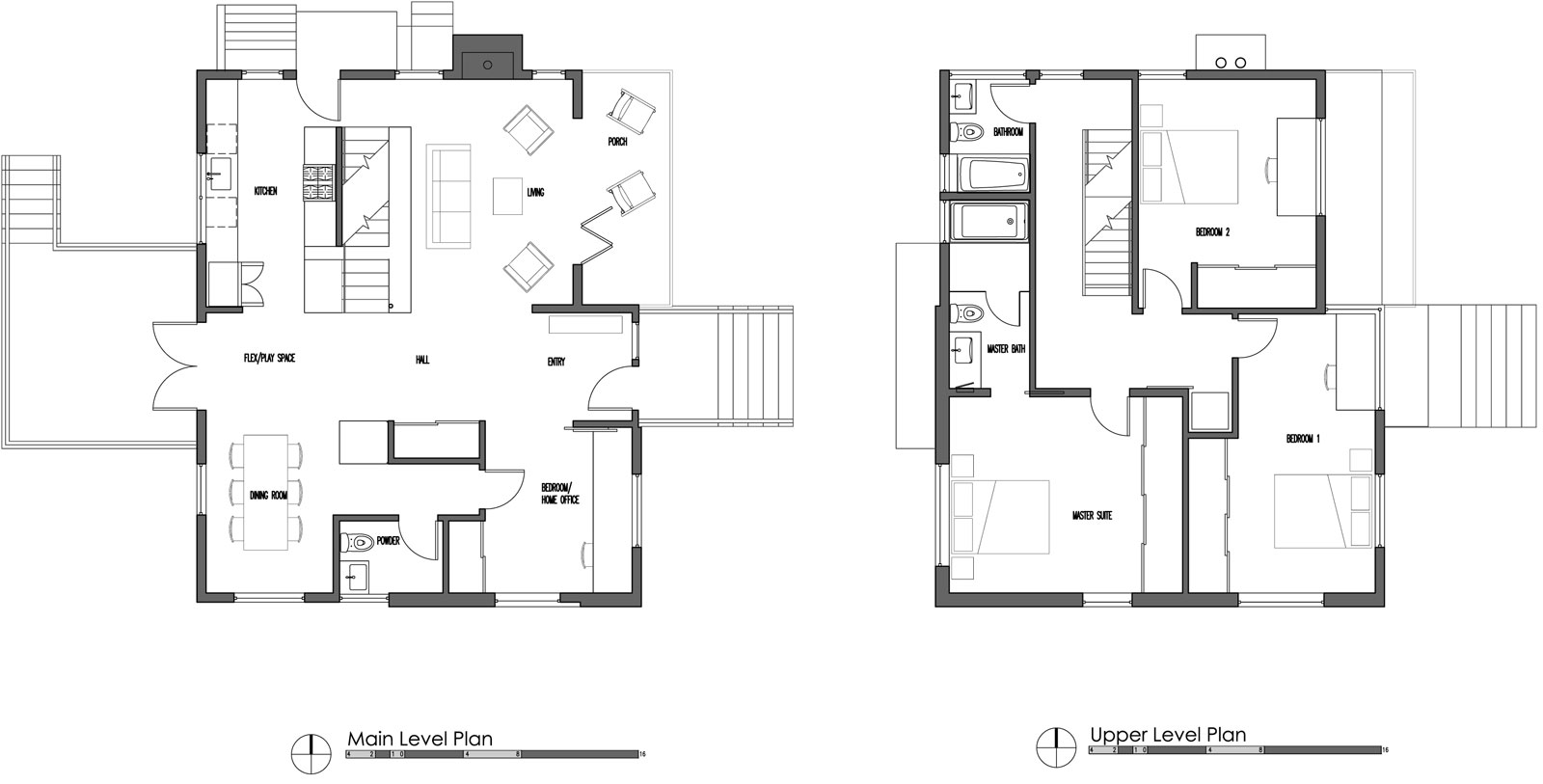

A recent project on Seattle’s Queen Anne Hill was designed to span the entire life cycle of a family, the owners intend on raising their family there and being part of the community for generations. The floor plans of the residence are basic with open common areas, light-filled bedrooms and a center circulation/stair corridor. The detailing is straight-forward with plenty of storage and Raumplus sliding walls that allow spaces to adjoin or remain private. The materials, like the maple flooring, are resilient (read: kid-proof) but also sophisticated and modern. Good, adaptable design should accommodate families for generations and subsequently eliminate the need to remodel every decade. One of the most sustainable practices typically goes unmentioned – not doing anything. The new design also uses 100% of the foundation from the previous home on the site (more on this below).

This home wasn’t designed to grace the pages of Architectural Record or to wave the banner of green design around, it was designed as a home for life.

Sensibility. Continually assert discipline in size, scale and program. Know when to subtract and streamline. Beauty and comfort result from intelligent solutions, not the reflexive addition of features.

Houses from the 1950s and onward usually have solid foundations that are 6 to 8 inches thick with a reasonable amount of steel reinforcing. Likewise, the wood framing holding these structures together is typically in good condition. Most of these components have performed well for the first 50 years of their life and we think they’ve easily got another 50 years in them (maybe even a hundred). We do everything we can to enroll clients in retaining these components and integrating them into “new” residences or substantial remodels.

Building on an existing foundation saves a tremendous amount of energy and fuel when you consider the excavation and trucking impacts. The raw material (concrete, formwork, steel reinforcing) required of new work also adds up in terms of the energy needed for manufacturing and shipping. Keeping as much framing as possible is a no-brainer, obviously retaining and reusing the existing lumber on site means less waste at the landfill and fewer trees at the mill.

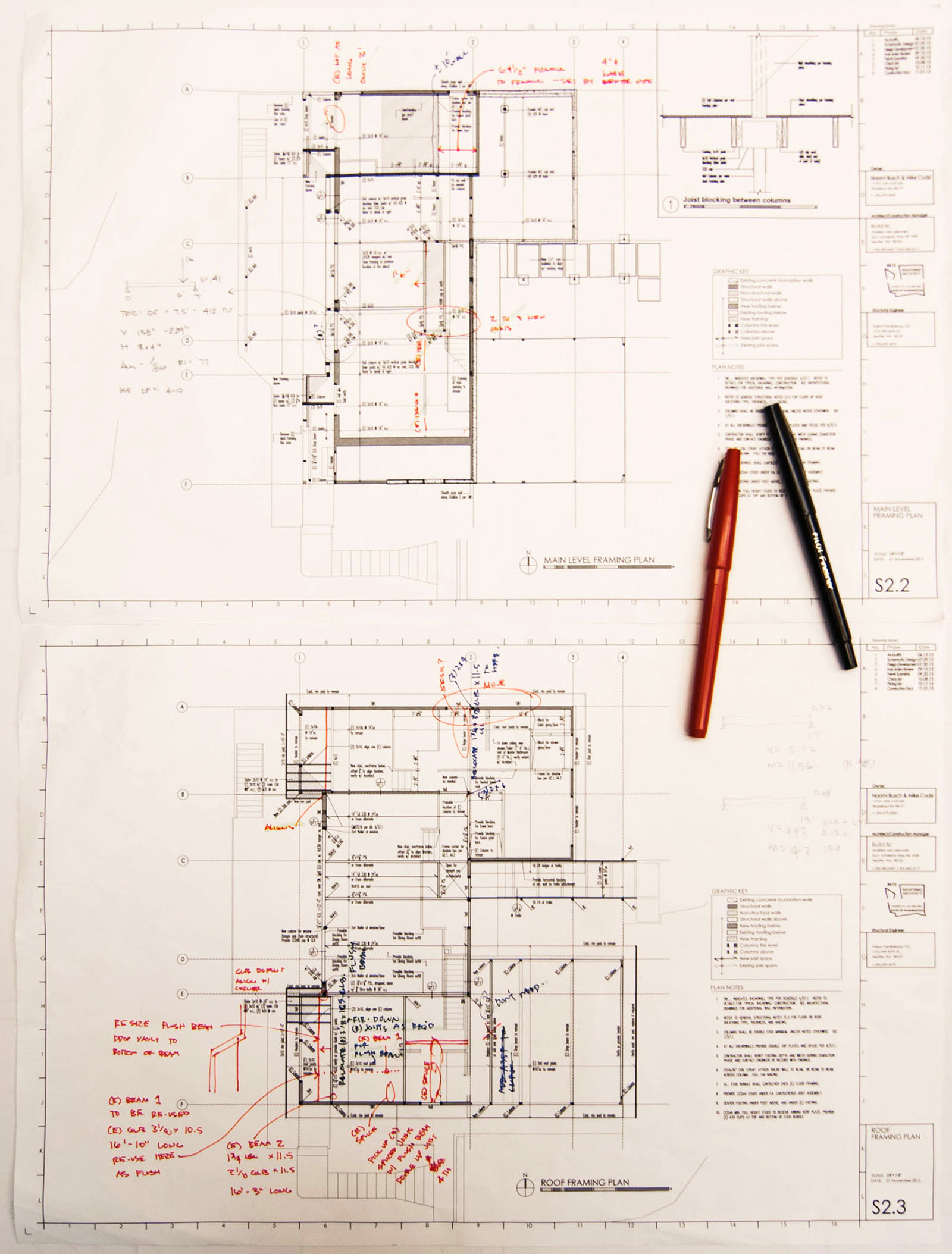

BUILD’s current Innis Arden project (just north of Seattle) preserves the foundation and saves a majority of the framing on an existing mid-century modern residence. During the design phase we brought the house up to 21st century standards in harmony with the existing envelope (removing only interior walls and 750 sf of roof). The project is now in construction and the demolition phase allowed us to verify the accuracy of our x-ray vision. If beams don’t exist where we thought they should, or if the structural members aren’t up to current code standards, we can usually figure out some resourceful ways to reuse beams and material removed from other areas of the structure. The drawings and notes below indicate our process from the site meeting; the notes indicate areas of concern at the existing structure, simple diagrams track where beams and framing might be moving to, and beam calculations resolve the shear, moment and deflection of existing beams at new locations.

The method is hands-on, the work is usually dirty and dusty, it requires architects to have a working knowledge of structure, and it makes for pretty mundane small talk at your next dinner party. But it saves a lot of material for the small cost of a bit of additional design time and some intelligent consideration.

Density. Incorporate the most people and activities that can sensibly be sustained in a given volume. There is a healthy balance between lawn covered neighborhoods and asphalt encased towers.

The idea that cities can continue to push outward with tract-house developments is failing all of us. It’s environmentally irresponsible, requires massive amounts of consumption (cars, highways, utilities, beauty bark) and quite frankly, doesn’t create places that most of us want to spend our precious time in. At the same time, individuals and families are desperate for a sense of community in their living environments.

There is a healthy balance of density that we’ve observed in places all over the world. From the town-houses in Vancouver and small multi-family buildings in San Francisco to the row-houses of Brooklyn and co-housing of Scandinavia, they all have one thing in common: These living arrangements give people a responsible amount of space to enjoy their lives, but not so much that it devastates the environment.

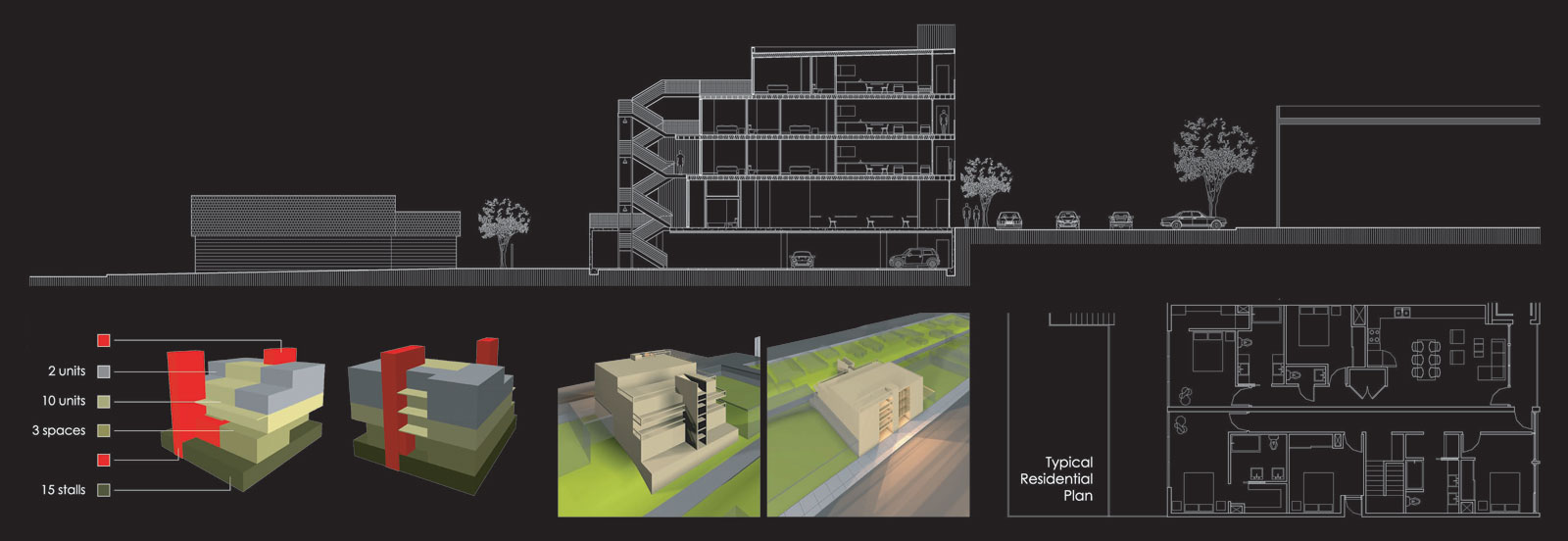

In 2007 we developed, designed and built the Park Modern building here in Seattle around precisely these ideas of adequate density, a sense of community, and group cooperation. Density also means shared land costs, and shared land costs means that most people can afford to live in the city, and when you live in the city you depend less on your car (and beauty bark). The Park Modern building includes 12 homes and 3 businesses, all of which sit neatly on a lot the size of 1.5 average single family parcels – a significant sharing of land costs.

For us it’s been a social study for the last 6 years and we’ve been thrilled with the results. It’s always difficult to convey the extraordinary quality of life we share in an environment like this. The kinship, the dinner parties, the cycling clubs, having our kids grow up together, and just the overall sense of community don’t fit neatly into a LEED rating system – but it’s one of the most sustainable projects we’ve ever done.

Regionalism. Use local resources: architects, contractors and materials.

The architecture world is as odds with itself on the issue of regionalism. Architects know that sustainable design depends heavily on localized design methods, and most architects (ourselves included) love to describe themselves as regionalists of a certain place and design philosophy. But many architects just can’t help themselves from the glamour and excitement of un-regionalism. As starchitects fly all over the world to complete with each other on dazzling design competitions, they set a terrible example that in order to be successful (or at least famous) you have to spend a disproportionate amount of time in the air. Rather, cities should foster and support their indigenous design talent. Similarly, it’s far too common for a project to tout itself on exotic materials from far-off lands when locally sourced materials actually give a project more character and genius loci.

The Pacific Northwest is gifted with exceptional natural resources and local talent. With an abundance of native wood varieties, and expert tradespeople everywhere you turn, it’s a shame to import much of anything from outside the region. The photos below highlight some of the carpenters, framers, electricians, tile setters, siders, steel workers, and painters that we work with on our projects. All of them are local, and we’ve worked with most of them for years (some even decades). Having a track record with these individuals builds trust, improves the finished product and keeps things local. Not to mention that we have plenty of great resources within the Northwest and West Coast for nearly all building components.

As regionalists we don’t have a portfolio of colorful work from around the world, or tales of that design competition in Dubai that we’re working on, but keeping our focus on the Pacific Northwest is a small contribution to sustainability –we also find that we’re happier when we get to see our kids everyday and maintain some basic fitness program.

Timelessness. Understand what forms and innovations will last. Reject fashion, pretension, and conscious efforts to attract attention.

Perhaps the most important, yet least discussed, key to sustainability is simply creating timeless design that will be appreciated for generations. Meaningful, cherished design doesn’t get torn down when a new design movement sweeps through; it’s taken care of over time by multiple generations. As the green design movement goes mainstream, it is just as subject to becoming a fashion as bad wallpaper. All the graywater tanks and solar panels in the world are useless in terms of sustainability if the home gets torn down within 50 years.

In our work we aim to craft a finished product that will withstand here-and-gone fads and the shifting tides of style. It’s a design philosophy rooted in pragmatism, function, technology and reason. Over the years we’ve discovered some floor plans to be more optimal than others, certain construction assemblies that outlast the alternatives, and specific elevation compositions that provide timeless visual harmony. In each case, the refinements rely on a practical, sensible design process.

A recently completed residence in the Beaux Arts Village community near Seattle was a scientific study of the environment, the program and an existing structure on the site. The design solution we arrived at was a pragmatic exercise involving constant design studies and advancing the schemes that performed best. Notions of style or creating something to draw attention were ignored as the exercise became one of translation and interpretation. The finished result reaches a balance between function and aesthetic. The house looks like what it’s doing, which to us is quite timeless. Not to mention that we were able to accommodate a larger multi-generational program on a footprint where an old cabin previously resided, all while removing just one tree.

People often misunderstand the role of an architect to mean that we paste onto a building some sort of style or flair. It’s actually quite the opposite – timeless, sustainable design is a process of discipline. Editing and subtracting are some of the most important tools in our toolbox. It may disappoint the preconceived projections of what architects do, but it serves the larger purpose of making the built environment healthier and more sustainable.