[Image by BUILD LLC]

Over the last several years, there’s been an abundance of media coverage on America’s growing urban populations, and data suggests that virtually all of the nation’s population growth is taking place in metropolitan areas. As one of most rapidly growing cities, Seattle is no exception to this trend, with city planners in 2006 predicting a population growth of 200,000 people by 2040. All of this urban population acceleration coupled with the severe limitations of geography creates a challenging situation for planners, developers, architects, and the community at large.

The good news is people want to live in the heart of the city. They want to be part of the urban culture, walk to their favorite local restaurants, meet friends at a neighborhood café, and commute by bike in Seattle’s shiny new bike lanes. You’ll find no complaints amongst us urbanites on this matter — it is precisely the population and diversity of different people from different places that makes a city come to life. The bad news is that Seattle is only just catching up with its projected housing requirements. In many cases the needed development is occurring ahead of the actual city planning. Specifically, we’re starting to notice key neighborhoods in Seattle that were designated long ago as a zoning type that does little to enhance its current social and community potential.

Today’s blog post looks into one of these neighborhoods which has outgrown its zoning. Seattle’s Central District has been the focus of our attention over the last several months as we’re currently involved in a significant project at 12th Avenue and East Spruce Street. While we’ll review several details specific to Seattle and this project, these examples also serve to forward the larger conversation of advancement of the urban built environment.

With the First Central Station project, the design team (B9 Architects, Weinstein A+U, and BUILD LLC) started with a research and gathering phase which, among other things, led to a series of diagrams. These diagrams unravel each layer of the neighborhood with a different lens: zoning, history, places of significance, people patterns, etc. A closer look at these studies can be found in a recent blog post, and we recommend an exercise like this for any urban mixed-use project. The diagrams offered the design team a deeper understanding of the site in its context, informing the proposed site plan, and will serve as a useful reference as the project progresses.

One of the most important discoveries with First Central Station was a schism between the urban environment and the existing zoning of the site. The existing zoning of Low-Rise 3 (LR3) on a portion of the site imposed a 40’ height limit and a relatively low density (a 2.0 FAR for you pros out there). In order to make a project like this pencil under these municipal codes, the entire site would be consumed by four-story apartment buildings and what would most likely be surface parking. Outdoor space would either be residual space of marginal public benefit or entirely internal and privatized. Additionally, the LR3 development isn’t required to provide any street activation or public open space.

The diagramming study brought us to the conclusion that, even without maximizing the density, going through a contract rezone process to change the overall zoning to NC2-65 (neighborhood commercial 2, with a 65’ height limit) would utilize additional density but less overall lot area, which would allow for the creation of meaningful, ground level, open space. The increased density would also support street activation by creating ground floor commercial spaces and provide a diversity of apartment types at different affordability levels. The change in zoning would lead to a site with sensible buildings and usable landscapes on par with the growing city around it. Going through the contract rezone process seemed like a no-brainer from urban planning, community-building, and architectural standpoints. This proposed zoning change, however, initiates a significantly more complicated, time-consuming, and costly permitting process. And while it adds nearly one full year to the design and permitting process, our developer client and team felt it was the right thing to do for our city.

Throughout the research and gathering phase, the design team has been meeting with community advocacy groups such as the 12th Avenue Stewards, Central Area Land Use Review Committee (CA LURC), Capitol Hill Housing, as well as Historic Seattle (the building owner of the adjacent Washington Hall), and a few others. Involvement with these groups has been instrumental to understanding the neighborhood and crafting the master plan for the site since they each have a vested interest in the project. The meetings have led to productive discussions and valuable feedback from the community groups. The comments, questions, and concerns informed a series of further explorations to the design process and aided in the development of a master site plan.

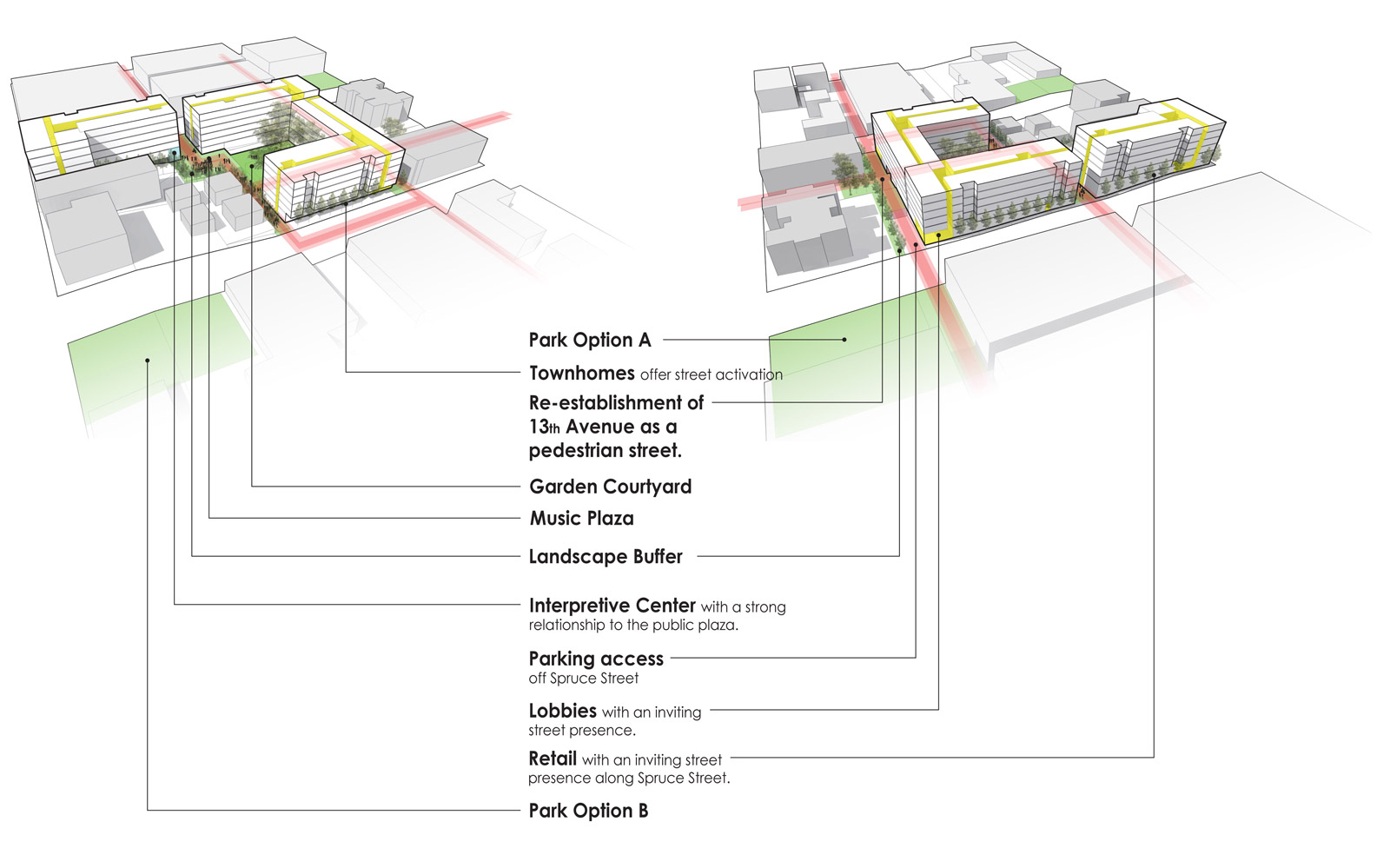

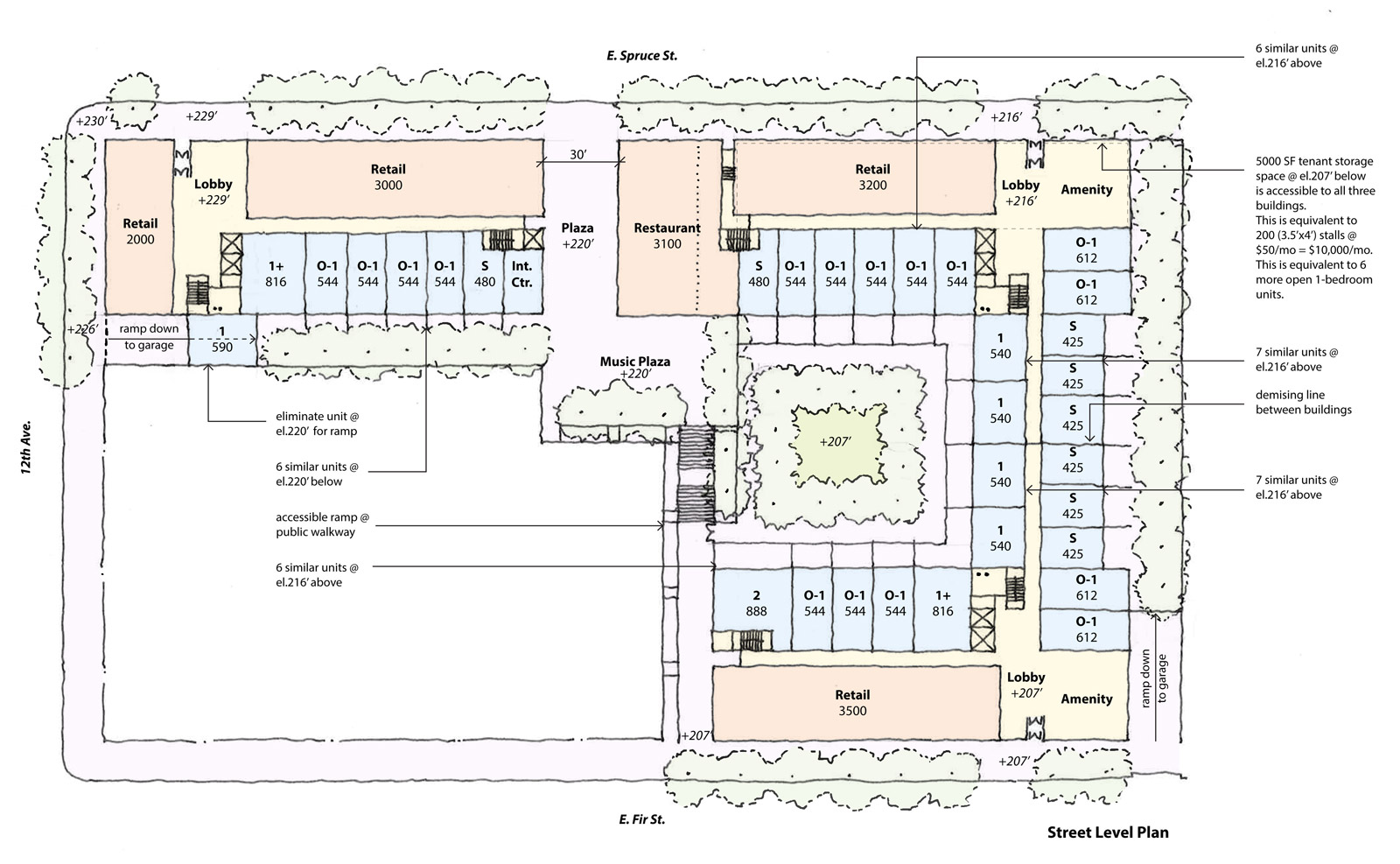

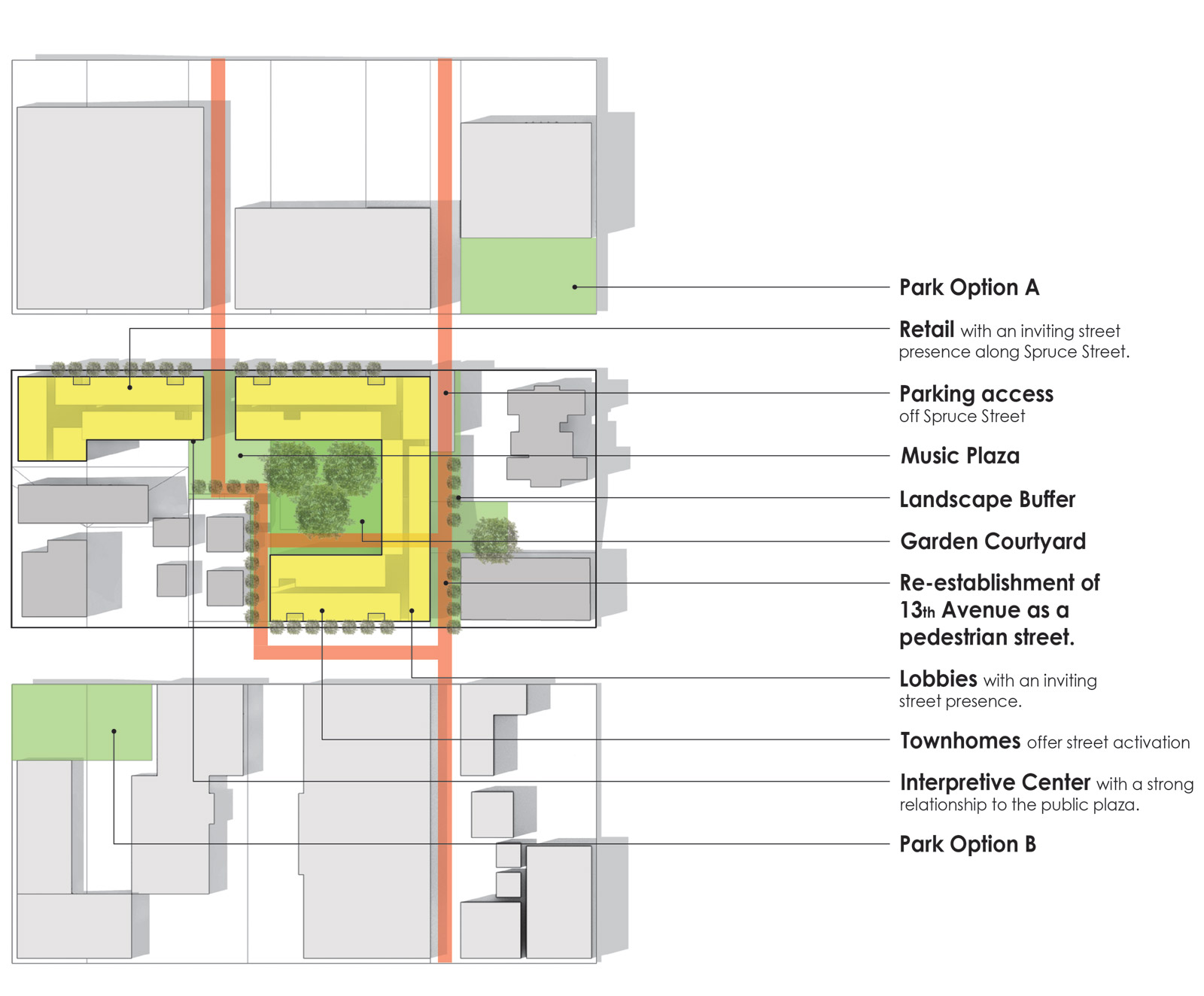

The initial master plan, beyond proposing the zoning change to NC2-65, incorporated several important design moves including a large privately-maintained, publicly-accessible open space in the center, an adjacent music plaza and interpretive center, the continuation of 13th Avenue (a portion of which was abandoned as some point) to connect East Fir and East Spruce Streets, along with the ground floor retail to engage the street, adding tree buffer zones, and providing underground parking accessed from a ramp along East Fir Street. The master plan also breaks up the overall massing into 3 distinct buildings, each designed by a separate architecture firm. While we are working in close coordination with B9 Architects and Weinstein A+U, this approach automatically builds in a diversity with the architecture for the project.

[Image by Weinstein A+U]

Using feedback from the community, the master plan evolved into a scheme that involved relocating the garage access to East Spruce Street to maintain East Fir Street as a pedestrian zone (and a pathway for children going to a nearby school), widening the passage through the site and to the publicly accessible open space, and moving the building lobbies to the corners for an increased buffer between new retail and existing adjacent buildings. Additional entry points from the east were established in what we like to call a “highly permeable site,” and open space at the east was enlarged to embrace a series of potential building upgrades to Washington Hall (independent of this project).

[Image by Weinstein A+U]

As the public meetings to address the master plan have moved toward completion, so has the site diagram. Our preferred scheme (which will be submitted to initiate the formal City review process) indicates the three building volumes, the permeability of the site via five access points, the string of open spaces for different purposes, tree buffer zones, retail activation along East Spruce Street, and one additional park component. In coordinating with the community groups and working with the Seattle Parks Department, the developer, Robert Hardy, elected to help finance an additional park adjacent to the site. The City had been looking to establish a public park in the neighborhood for some time and the stars aligned with the timing of this project. Currently, there are two proposed sites for a park of 10,000 square feet: the primary location at East Spruce Street and 14th Avenue or a second option at East Fir Street and 12th Avenue. If there were ever concerns about a development team’s responsiveness to a neighborhood, we were committed to fully addressing them — through the creation of buildings and open spaces that embrace the neighborhood as well as helping to finance an adjacent park that the neighborhood has been striving to achieve for about a decade.

[Image by BUILD LLC]

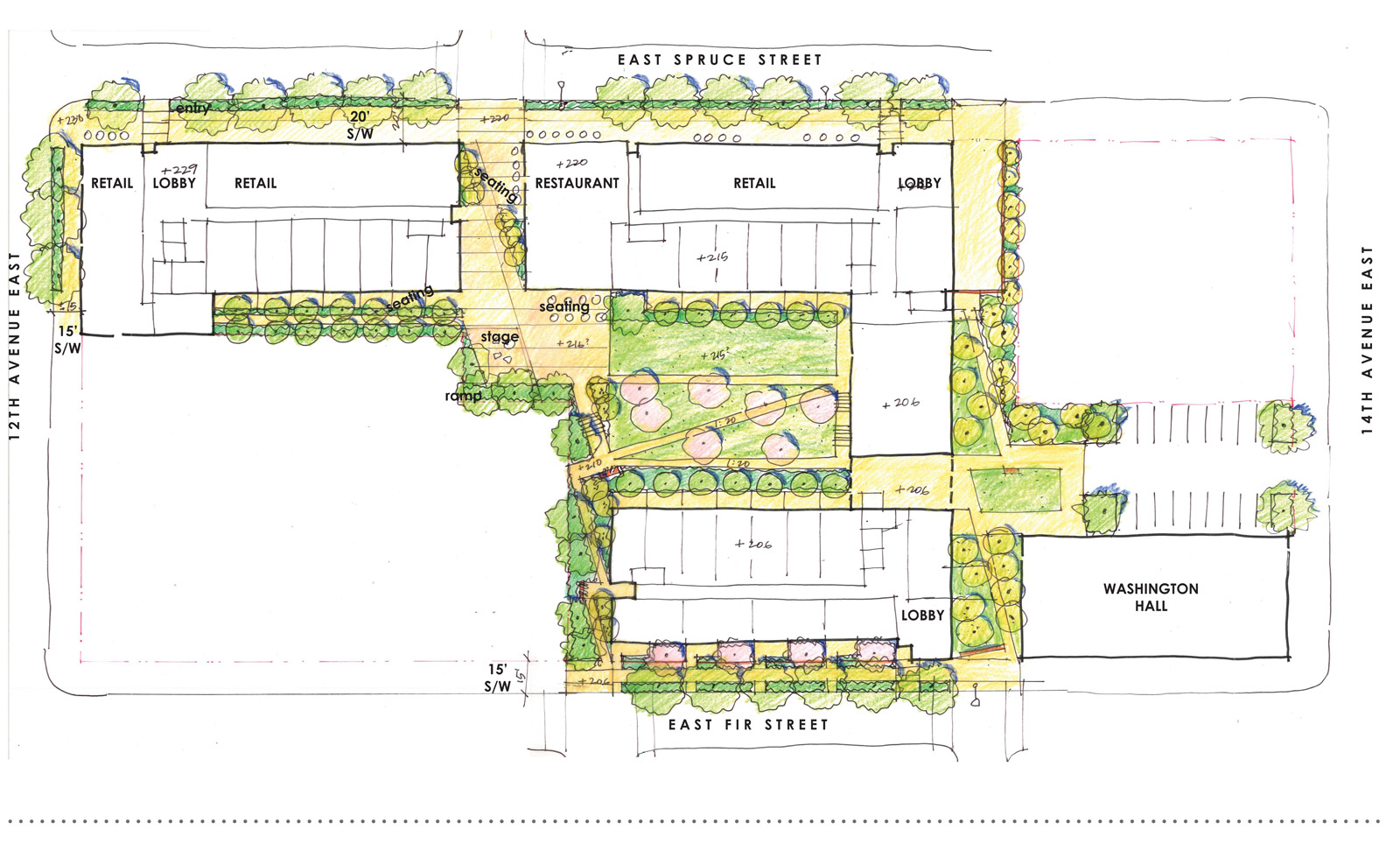

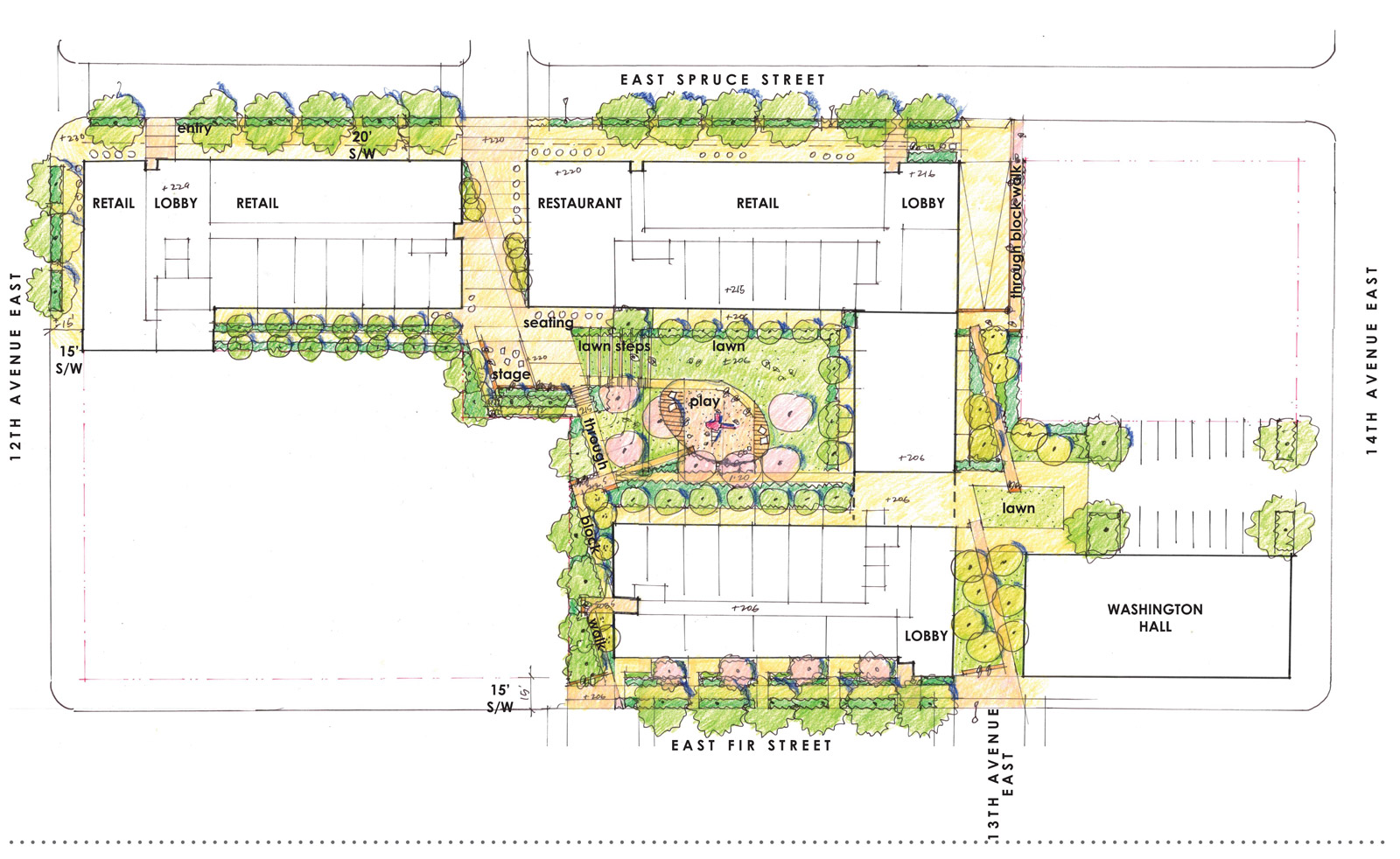

Landscape architect Karen Kiest was recently brought on board to develop the open spaces of the site, which has produced the plan below. The design established a more dynamic experience of the exterior spaces, with better focus on activating the outdoor areas.

[Image by Karen Kiest Landscape Architects]

Further enhancements to the landscaping plan have developed terraced seating, a kids play area, a sequence of experiences through the site, and thoughtful connection points between the landscape functions.

[Image by Karen Kiest Landscape Architects]

Imagining this development confined to a lesser LR3 zoning designation produces a list of missed opportunities and a dissonance to the city around it. In some situations, cities are looking into their crystal ball and rezoning underutilized urban areas prior to development proposals. In other cases, like the 12th Avenue and East Spruce site, it’s up to the architectural team to sort out the data, come to an intelligent conclusion and, if it’s the appropriate answer, propose a rezone to the community and the city. This design process has reinforced the rezone to NC2-65 and we’re excited about the prospects for this block of Seattle.

As urban planners, architects, landscape architects, designers, and people who simply enjoy living in the city and thinking about good design, it doesn’t get much better than this. Projects of this complexity and potential community benefit are what most of us on the design team were trained to do in school, and it’s exactly what we love getting our heads around in the profession. Figuring out new solutions that activate neighborhoods, honor communities, and provide value to the city is what gets us up in the morning ready to put pen to paper. It’s been a privilege to be a design team member on this project, and we’re looking forward to covering more of First Central Station as it evolves.

Cheers from Team BUILD