In summer 2015, BUILD sat down with Peter Bohlin and Ray Calabro of Bohlin Cywinski Jackson at their Seattle office to discuss their process of designing everything from art galleries to books, and the importance of understanding clients. We hope you enjoy this interview from our archives. Part 2 of the interview can be read here.

How did Bohlin Cywinski Jackson get its start in the Pacific Northwest?

How did Bohlin Cywinski Jackson get its start in the Pacific Northwest?

Peter Bohlin: Early projects, such as Forest House and the first house I designed for my parents, were both published in The New York Times. The Forest House was a cultural icon for architects and still is. I think it’s why we were selected to compete to design Bill Gates’s residence, which was a joint venture with Cutler Anderson Architects on Bainbridge Island. When he was at the University of Pennsylvania, Jim Cutler worked in our office and he and I became friends. If we were going to design the Gates residence, I felt we needed to be here in the Pacific Northwest. During the competition, the BCJ design team lived on a boat in Eagle Harbor on Bainbridge Island, and we shared an office space with Jim Cutler. We ended up winning the project. As the Gates project was nearing completion, we began to win additional work locally and saw the benefit of having an office in downtown Seattle.

BCJ has worked with Steve Jobs on many of the well-known Apple Stores around the world, and the Pixar headquarters in California where he was CEO. How did you find a working balance with Jobs, who was known for bringing a strong, often tenacious vision to the table about how things should look and function?

Ray Calabro: Steve appreciated our work and appreciated Peter because he worked hard to understand the nature of each client and their circumstances. Understanding Steve’s desire for symmetry, for instance, was really crucial to him. Other architects might not have been as perceptive or willing to listen; some would be more interested in imposing their own will.

What do you look for in clients in order to begin a project together?

PB: When we work with institutions, it’s important for us to identify people who believe in us and want to engage throughout the design process. This interplay allows us to arrive at a better place than if we simply designed a project on our own.

RC: Some of our more appreciative clients are those who’ve been most enthusiastic about the process; it’s more than designing a house—it’s about how it will make them feel, how the project will change their patterns and what they see. Perceptiveness is a quality we like in clients.

In Hawai’i, we designed a gallery space, the Waipolu Gallery and Studio, for a very private client. He’s a collector of mid-century modern art, and the gallery was just for him. The genius of the space is that it captures a view of Diamond Head crater and the ocean simultaneously, in one structure The client said it exceeded his expectations. He was very engaged but not dictatorial. In most cases, we gain the client’s trust; once that happens, they’re willing to take leaps with us. And then there are times when a client is set on working with us. Currently, we’re working with a developer on the Eastside who selected us for a large-scale project. Even though we turned it down a couple of times, he demonstrated a really great interest in design, and was persistent about producing something together.

PB: The ones you turn down a couple times often turn into better clients. You work with many clients who may assume perfection.

How do you properly set expectations?

RC: Some of the expectation-setting happens when we take them to see other buildings we’ve done. It can be a revelation for them. On one of these visits, a particular client expressed their appreciation of how beautiful materials related to each other and were detailed to a level of precision. They recognized that it was the collective result of a good architect and a good builder, and it changed the way they were thinking about their project. Seeing past work of ours demonstrated the level of detail we achieve with projects.

PB: I would say “care” rather than “detail.” There isn’t always money to create lavish details, and sometimes you don’t want to. Sometimes details can get in the way of the dream.

RC: Setting expectations around the issue of care can also transpire by visiting projects that the client likes that were designed by another firm. Other times we have clients who come in having seen a certain project and say, “We want to go well beyond that.” And you have to live up to it. In these situations, Peter reminds us that you can’t drop the ball, you have to own up to the opportunity you’ve been given.

PB: We’re always doing modest things, too, like working with the Girl Scouts, which involves a different level of expectation. We did one building a year for them, and they funded it with cookie money. We’re always working on a range of projects, and it’s good because it stretches us; we don’t get into one habit of thinking. It’s a little challenging because sometimes we get into a certain pattern of designing and try to apply that approach elsewhere. It doesn’t work very well.

Living up to those expectations through drawings is one thing, but how do you control the execution of the design in its built form?

PB: Sometimes you can’t. That’s when you have to decide what’s important and what’s not.

RC: We try to have good document sets to work from. And it’s important to have a strong relationship with the builder. You also have to want to be on site and to be part of the conversations that happen there. A lot of it is demonstrating that you care about the final outcome.

PB: It’s always about deciding. Things aren’t equally important nor equally achievable, whether it’s the ability of a builder, the size of the budget, the caliber of people involved, or the scale of the endeavor.

One of the challenges with high-end luxury homes is that the owners can enjoy the process of design to the extent that they don’t necessarily want it to end. How does your firm maintain discipline and resolution regarding a project’s timeline?

One of the challenges with high-end luxury homes is that the owners can enjoy the process of design to the extent that they don’t necessarily want it to end. How does your firm maintain discipline and resolution regarding a project’s timeline?

RC: I’m reminded of a past project, the Gosline Residence in Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood. Our clients were a couple who really enjoyed the process. It wasn’t that they didn’t want it to end, but after the project was completed, the owners would invite the entire office (which at the time was much smaller) over to the house about once a year. The process had a life beyond the built project, and they wanted us to participate in the dialogue. They loved that the house could accommodate and take on different uses that they could never have imagined.

What inspired the decision to design everything down to the furniture for Seattle’s Ballard Library and Neighborhood Service Center?

RC: We had a very modest budget on that project. It was initially designed with a furniture package that consisted of mass-market pieces, but that ended up being more costly than the available budget. It was the insight of Robert Miller, the principal-in-charge of the Ballard Library, that led us to design and build the furniture for less money than it would take to buy it commercially, particularly for the tables. We used Eames fiberglass shell chairs, but the lounge furniture, tables, and children’s furniture were all custom-designed. Robert had an interest in notch-and-tab furniture. The theory was that if we could build everything based on a 4’x8’ sheet of plywood, there would be little waste and the furniture could be shipped flat from the manufacturer. One night at the library, folks from the branch and our office assembled the pieces with rubber mallets. We didn’t use any adhesive or mechanical connections. It was a way of leveraging a modest budget.

You’ve also designed some very beautiful books. How does the process of designing a book differ from the process of architecture?

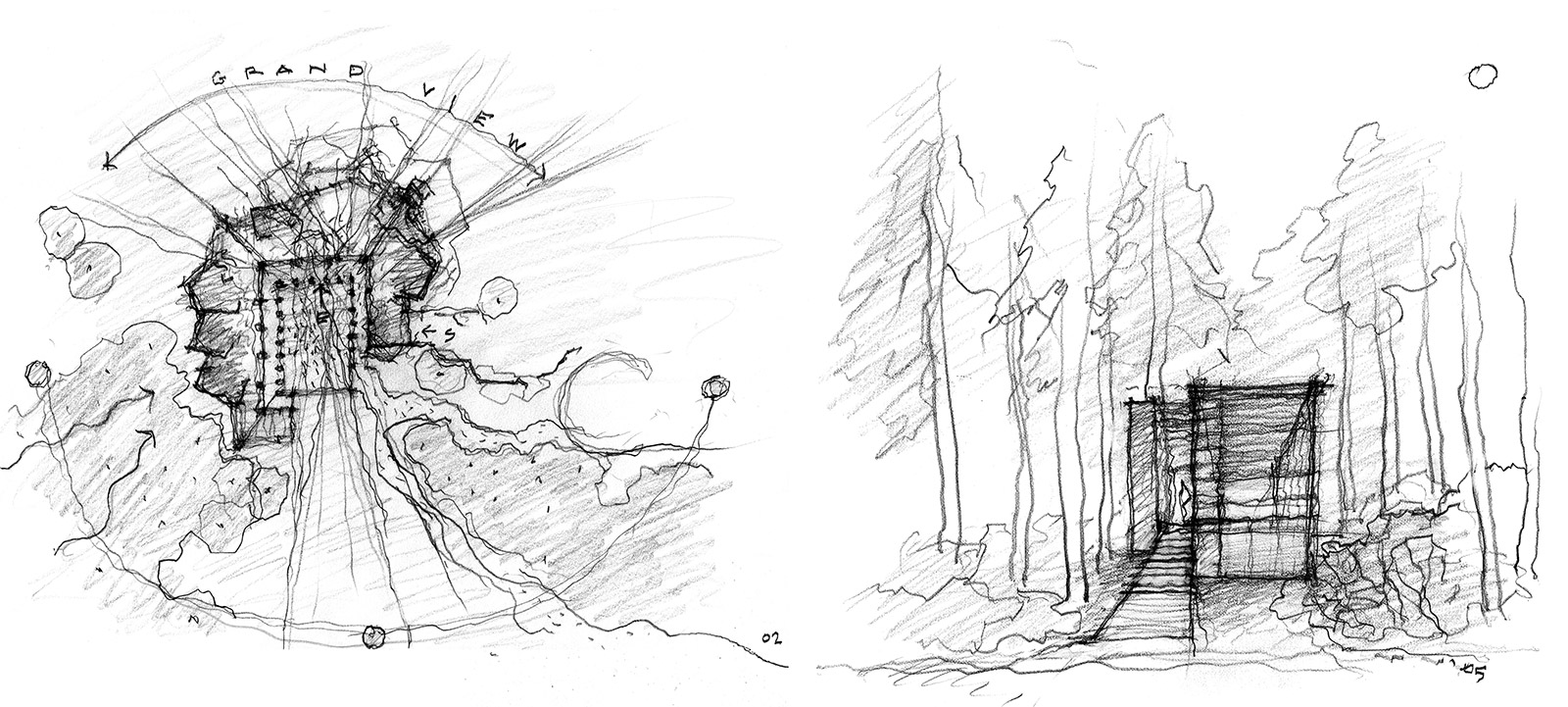

RC: Peter and I are very involved in making the books. We believe in presenting our work in a way that speaks to the spirit of the building. The combination of images, drawings and sketches provide insight into the way we work. There’s a new book coming out in October called Listening, which presents 12 houses from the last six years of our practice. Within it is an essay called “Stitching a House” by Alexandra Lang, who we met when she first wrote about us a few years ago.

Peter has always been interested in getting great photography of our projects, even in the early days of the practice. Back then we worked with Joe Molitor and some of the other talented architectural photographers of the time. There’s tremendous value in images of your work since these days there are so many ways of reaching people beyond just printed photos; they play into social media and websites, and that’s a great thing. We have a history of having beautiful images of our projects and showing that work to others in a strong way.

BIOS:

Peter Bohlin, FAIA, is a founding principal of Bohlin Cywinski Jackson and one of America’s leading architects in practice today. Founded in 1965 in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, with Richard Powell, the firm has expanded to five offices in Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Seattle and San Francisco. In 1994, the firm received the AIA Architecture Firm Award. In 2010, the AIA awarded Peter their Gold Medal, the highest honor they bestow upon an individual in the profession. bcj.com

Peter Bohlin, FAIA, is a founding principal of Bohlin Cywinski Jackson and one of America’s leading architects in practice today. Founded in 1965 in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, with Richard Powell, the firm has expanded to five offices in Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Seattle and San Francisco. In 1994, the firm received the AIA Architecture Firm Award. In 2010, the AIA awarded Peter their Gold Medal, the highest honor they bestow upon an individual in the profession. bcj.com

Ray Calabro, FAIA, holds a Bachelor of Architecture degree from Virginia Tech and is a principal at Bohlin Cywinski Jackson. A member of the firm since 1995, Ray’s experience includes visitor centers, corporate headquarters, academic buildings for science and research, and private residences across the western United States and Canada. His leadership and vision are most clearly demonstrated by the award-winning Grand Teton Discovery and Visitor Center in Jackson, Wyoming. He also leads Bohlin Cywinski Jackson’s publication efforts.

Ray Calabro, FAIA, holds a Bachelor of Architecture degree from Virginia Tech and is a principal at Bohlin Cywinski Jackson. A member of the firm since 1995, Ray’s experience includes visitor centers, corporate headquarters, academic buildings for science and research, and private residences across the western United States and Canada. His leadership and vision are most clearly demonstrated by the award-winning Grand Teton Discovery and Visitor Center in Jackson, Wyoming. He also leads Bohlin Cywinski Jackson’s publication efforts.