The constant growth and complexity of the building code has been a concern of ours for years. Simply put, the beastly size of the code is the bane of most architect’s existence, and while we love a good hyperbolic rant, we’ll be focusing on the no-nonsense, objective data here. A recent talk we gave for the Northwest Eco Building Guild allowed us the welcomed opportunity to perform a deep-dive into the actual metrics of the International Building Code (IBC), which proved extremely insightful. This article presents our findings related to the frequency of building code releases, and how the document has changed over the years—and we admit that there may be a tirade here and there just to keep our wits in check.

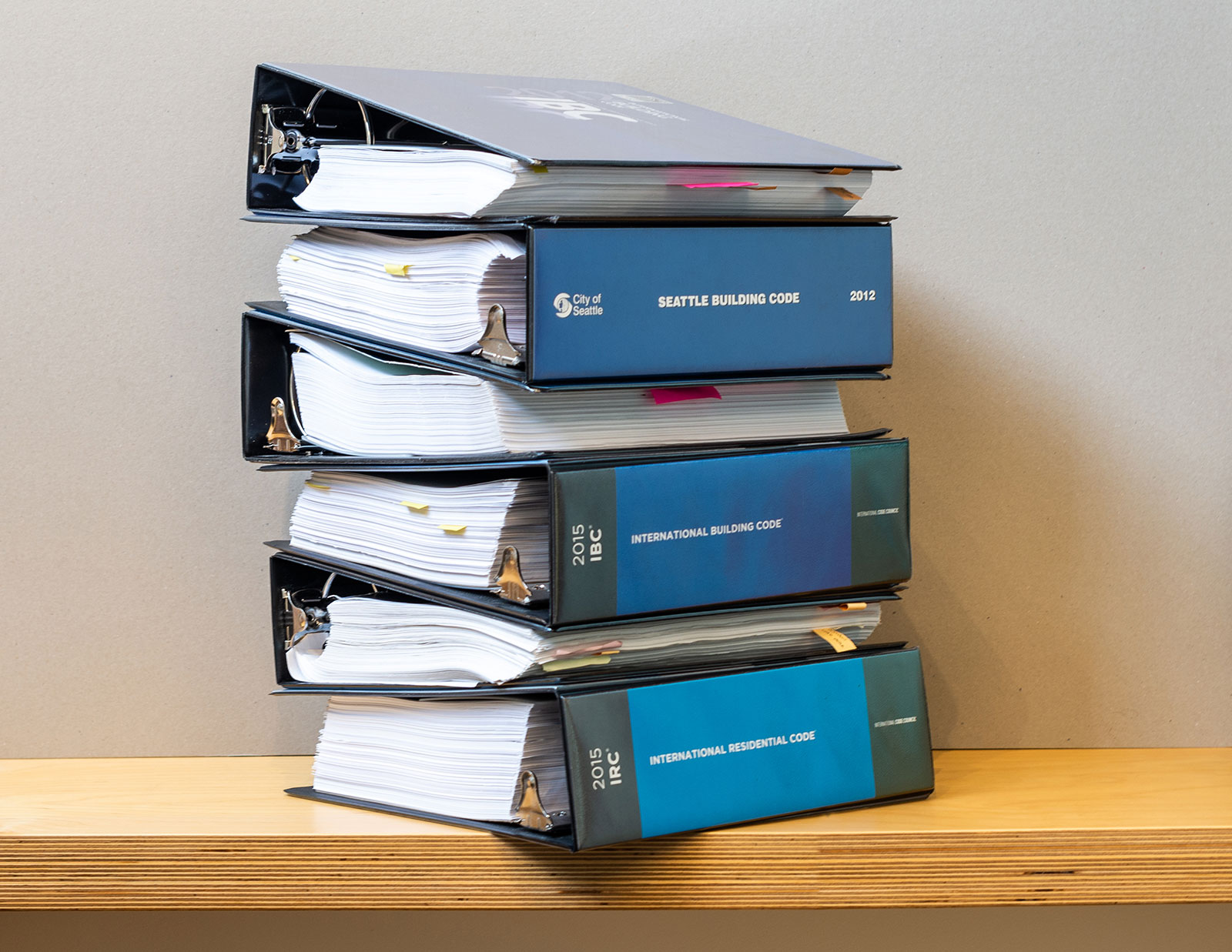

The photo shown above captures what might be the most significant evolutionary moment of the code over the last 100 years. Up until the mid-1990s, the code was a small book that you could throw in a bag on your way to the jobsite. This datapoint alone represents volumes about how architects used to work. Up until the 1990s, architects could reference the code on the jobsite and problem solve in the field. With its current size and weight, it now requires its own table in most offices. Because it can’t simply be transported in a bag, referencing the code and problem solving on the jobsite is much more difficult (hauling the current codes to the jobsite practically requires a trailer). So, the overwhelming size and complexity of these codes is partially responsible for turning architects into permit technicians rather than professionals who can roll up their sleeves and problem solve in the field. This photo begs the question of how this came to be.

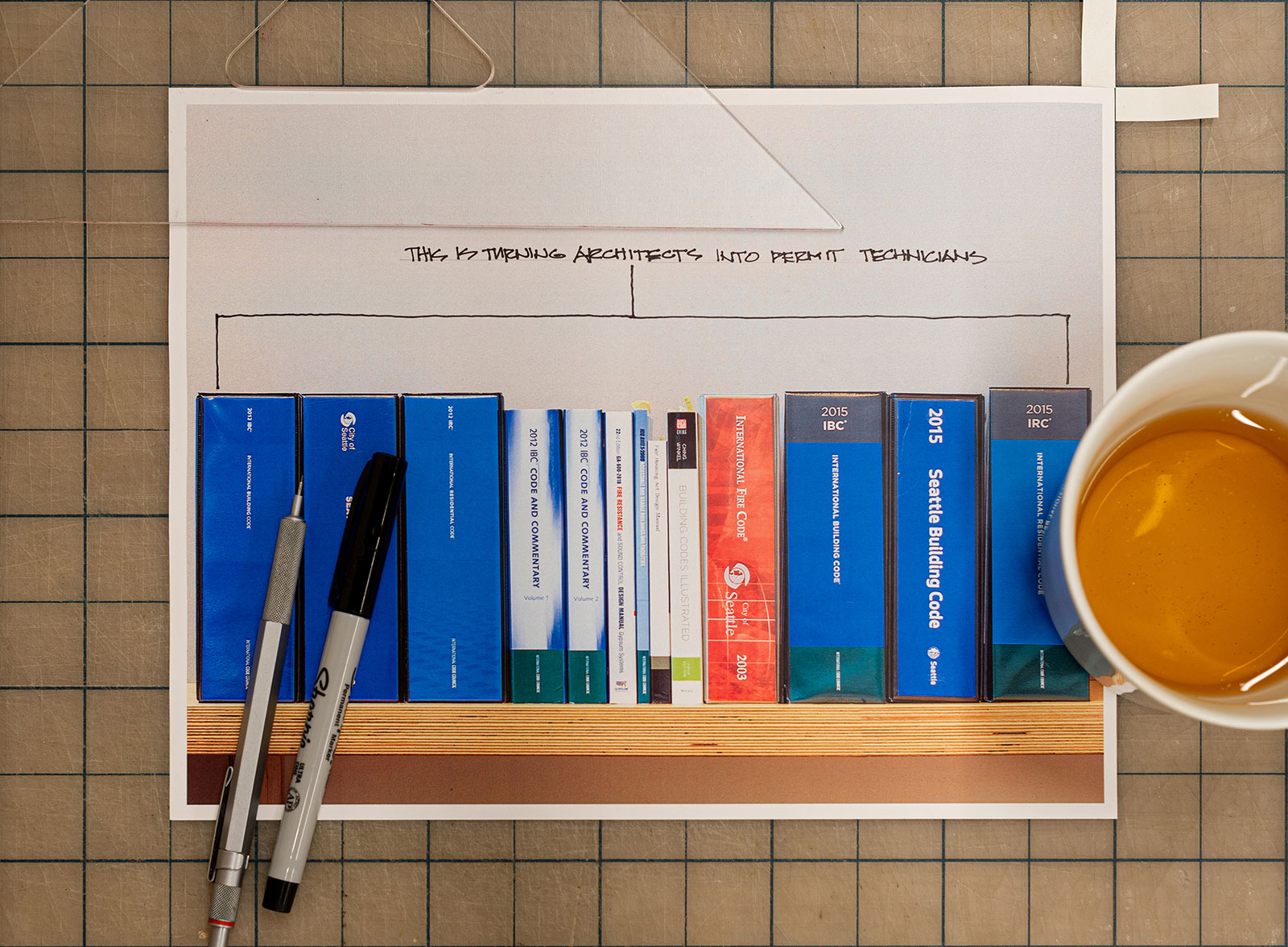

This photo shows the relevant codes that were used here in the BUILD office up through 2016; note that the subsequent 2015 and 2018 codes have grown in size and complexity. These codes include: the International Building Code (IBC); the International Residential Code (IRC); the Seattle Building Code (SBC); Building Codes Illustrated, for when you need a drawing or diagram for the commentaries (we wish we were making this stuff up); a Fire Resistance manual for assemblies; two versions of the Accessibility Code, which sometime conflict with one another; and commentaries on the codes (because they’re written in such arcane language, it takes a separate book to translate them).

The International Code Council (ICC) releases a new UBC/IBC every three years, and jurisdictions have the option to adopt these codes as they like (the code was called the Uniform Building Code until 2000, or UBC, and then the title changed to the International Building Code, or IBC, from that point forward). Here in Seattle, an every three-year cycle of adopting a new code started in the 1940s, and has since become an industry unto itself. Companies have been formed for the sole purpose to steward the cyclical publication of the code, and an army of employees depend on each new release to make a living. So, it’s safe to say that this three-year pace isn’t going to ease up—if anything it will only become more frequent. The concern is, of course, do we really need new building codes every three years?

Additionally, with the IBC changing and being reissued every three years, there’s a subsequent trickle-down effect with each of these supplementary documents. Changes to the UBC or IBC have a direct impact on State and City amendments and all of the ancillary codes mentioned above.

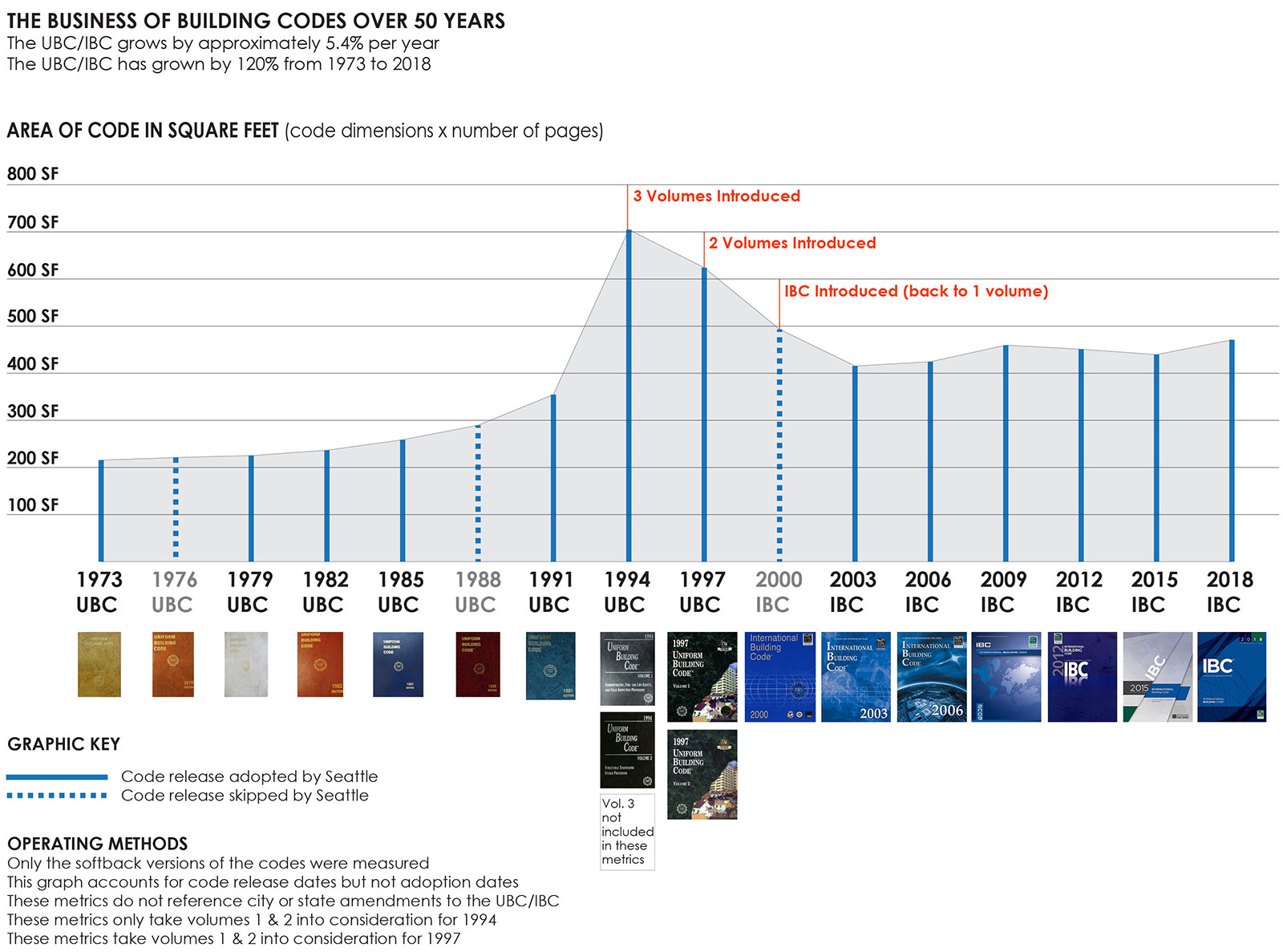

We began this study by working to understand the facts and knowing that a critical piece of the puzzle must include how much the code has grown over a period of time; we chose approximately 50 years because it’s relevant to our colleagues and we were able to collect and decipher the data in a few days rather than making a dissertation out of it. So, the graph below measures the size of the code from the 1973 edition to the present.

Evaluating these codes isn’t as straight-forward as we’d hoped, and we began to wonder if this was by design. The ICC is a slippery bunch, and they’ve changed some of the variables over the years. For instance, the physical dimensions of the code have occasionally changed; through the 1970s the code was a tidy 5.5” x 8”, and at a mere 700 pages it was small enough to fit in a bookbag as noted above. The dimensions increased slightly in 1991 and the page count exceeded 1,000. In 1994 the ICC threw a double-whammy at us with a 6.5” x 9” three volume set with an increased page count. In 1997 it shrank to two volumes, but the dimensions increased to 8.5” x 11”. Since then the the size has remained consistent, but the page count has continued to increase.

We needed a metric that took all of this into consideration without losing any data critical to this study. So, like any office full of frustrated architects, we relied on our old friend the square footage calc. The graph above illustrates each code release from 1973 as a simple calculation of its dimensions multiplied by its pages. For instance, the 1973 code is 5.5”-wide x 8”-tall, which results in an area of 44-square inches per page; multiply that by 700 pages and you get 30,800-square inches, or approximately 214-square feet of code pages (about enough to cover the floor of a bedroom). For comparative purposes, this metric was used on each code release from 1973 to 2018. We discussed a couple of different methods to analyze this data, like a count of code provisions in each issue or even a word count, which would be interesting measurements but would require camping out in a library archive for a month. What’s worth noting is that any single new code provision can have a significant effect on the built-environment, on permitting, and on construction costs.

Looking back to the square footage graph, we think it’s pretty clear that the 1994 code was taking performance enhancing drugs, based on the growth spike where it went from 356-square feet in 1991, to a massive 703-square foot three volume set in 1994 (performance like this just isn’t natural). Volume one covered administration, fire, and life safety; volume two structural, and volume three material testing and installation standards. We only used the metrics from volumes one and two for this graph, as the other codes also include life-safety and structural. Subsequently, in the 1997 release, the code was reduced to two volumes; then in 2000 it was further reigned in to one volume. This history makes us wonder if another spike is in our future.

There’s some other important info about this graph. The solid vertical lines are code releases that Seattle adopted, and the dashed lines are codes released by the ICC but not adopted by the City of Seattle. It’s also interesting to note that until 2012, Seattle skipped a code adoption every fourth cycle (refer to 1976, 1988, and 2000).

Overall, each new code has grown by an average of 5.4-percent. This sounds diminutive compared to our frustrations with the current unwieldy code, but it’s helpful to keep the compounding size in mind. The overall change between the 1973 and 2018 codes is an increase of 120-percent in area—which is worth being frustrated about if you’re an architect, a builder, a developer, a homeowner, or someone concerned with the well-being of the built-environment.

So, this study, the metrics, and the diagramming led us to a couple of conclusions.

Since code writing is now an industry, the publisher, distributors, sales-people, and everyone it takes to produce a new code are all incentivized to continue generating new ones. In other words, it’s unrealistic to expect that codes will be adopted less frequently. With that said, the City of Seattle’s historic practice of skipping a code adoption every 4th cycle was admirable because it allowed manufactures and suppliers to catch up with code requirements. Specifically, we’re thinking about the constantly increasing glazing U-values, and the race most manufacturers find themselves in every time a new code is adopted; some of our preferred glass producers didn’t get there fast enough and we’ve simply had to stop specifying their products here in Seattle. It also gives the architects, GCs, and consultants a chance to catch up. Bear in mind that this four-cycle break only occurs once every 12 years. Over the course of an architects career, they might only get this break 3 or 4 times if they’re lucky.

There are other good reasons for a city or county to dismiss a code release: cultural shifts, national, state, and city emergencies, and, dunno, maybe a global pandemic that shuts society down might also be a good reason to skip a cycle. While the design and construction industries appreciated the delay by most jurisdictions to adopt the 2018 IBC, avoiding this code adoption truly seemed like a sensible decision no matter what. Unfortunately, as of March, the 2018 IBC is now in effect here in Seattle.

There is real concern that a robust and constantly changing building code isn’t helping society when more and more of that society is living in a tent under a bridge. A larger and more complicated building code benefits those with means…and access to land use attorneys.

Given all of this, we propose going back to a practice of making a revision every third or fourth cycle. And so the code industry isn’t threatened and people aren’t losing their paychecks, we propose that this cycle focus on minimizing the code; the goal should be to reduce the content (or the square-foot metrics we’re discussing here). We’d even go so far as to propose that for every new code provision added, two outdated or irrelevant provisions are removed. This code cycle would be an act of curating and trimming—it would bring things back in balance and the objective should be to ge back to a code that we can throw in a our bag on the way to a jobsite. Let’s be problem solvers again rather than code technicians.

The lack of housing in our cities is a national emergency. Here in Washington State, King County declared a homeless state of emergency in 2015, and the building code and permitting processes aren’t making things any better. It’s time for the industry to look back and realize that the trajectory of ever-increasing codes is going to harm the built-environment in the long term. It’s time to set a precedent of trimming and curating the building code every several cycles. It’s time to be smarter.

We want to underscore that the ever-growing building code isn’t just an inconvenience or a frustration, it’s a significant barrier standing in the way of a more equitable built environment and more just society. In our opinion, if we can’t re-evaluate and course-correct now, we’ll spend the next several decades playing catch-up, we’ll continue wasting valuable resources, and we’ll exacerbate social inequality. It’s really important to remind ourselves that everything discussed here is a mechanism contrived by humans. The size of the building code, the frequency with which it is adopted, and the content itself are all devices entirely made up by people. This isn’t to say that they don’t serve a purpose, but we’re simply proposing that we change what isn’t working.

Cheers from team BUILD