In most cities, developing multi-family buildings is expensive, time-consuming, and stressful; as such, development teams must be resilient, determined, and have abundant resources. One of the primary catalysts for this frustrating situation is that jurisdictions typically demand a design review process prior to allowing receipt of the master use and building permit submittals. It’s almost a sure bet that the bigger the city, the more complicated and involved the design review process will be. For instance, in a city like Seattle the design review process is an eight to ten month commitment, which begins with early community outreach, where the architect and development team reach out to the community to solicit feedback during the design phase. We’ve written extensively about the controversy of early community outreach and the perils of working through the design review process, and there continues to be ongoing debate in most cities as to whether these lengthy processes actually produce better built-environments. But more importantly, can investors, developers, architects, and builders survive the protracted permitting timelines, excessive fees, and overreaching design directives inflicted by the design review process? Today’s post isn’t a criticism of the system; instead it proffers a strategy, using the permitting process, which causes less damage and risk to investors, developers, and architects.

Small, resourceful firms like BUILD are always looking for better, more effective ways to get projects designed, permitted and built; it’s part survival instinct and part desire to be leaner, smarter, and scrappier. More, it’s a core belief of ours that providing affordable housing to the masses shouldn’t be so costly, and we refuse to accept that a multi-family project should take 18-24 months simply to permit (Seattle’s current timeline). In many ways, the multi-family equation is the perfect arena to craft and test strategies. Learning how best to navigate the land use and building codes, and find the optimal balance between time, cost, and value are also key to becoming a master architect. Over the years, we’ve also had the benefit of cross-pollinating with many like-minded CEOs, developers, architects, builders, and project reps who have each added an important contribution to solving the multi-family puzzle.

A current multi-family building on our desks here at BUILD is a crystal-clear example of the efficiencies that can be identified, utilized, and leveraged for small development projects. This project is effective to the extent that it avoids the entire design review and early community outreach processes altogether—and is entirely above board and code conforming. We’ll use this apartment building project, located in Seattle’s Ballard neighborhood, as an example to break down the process into ten critical pre-permit components.

TARGET THE RIGHT ZONE AND FORGET ABOUT THE REST

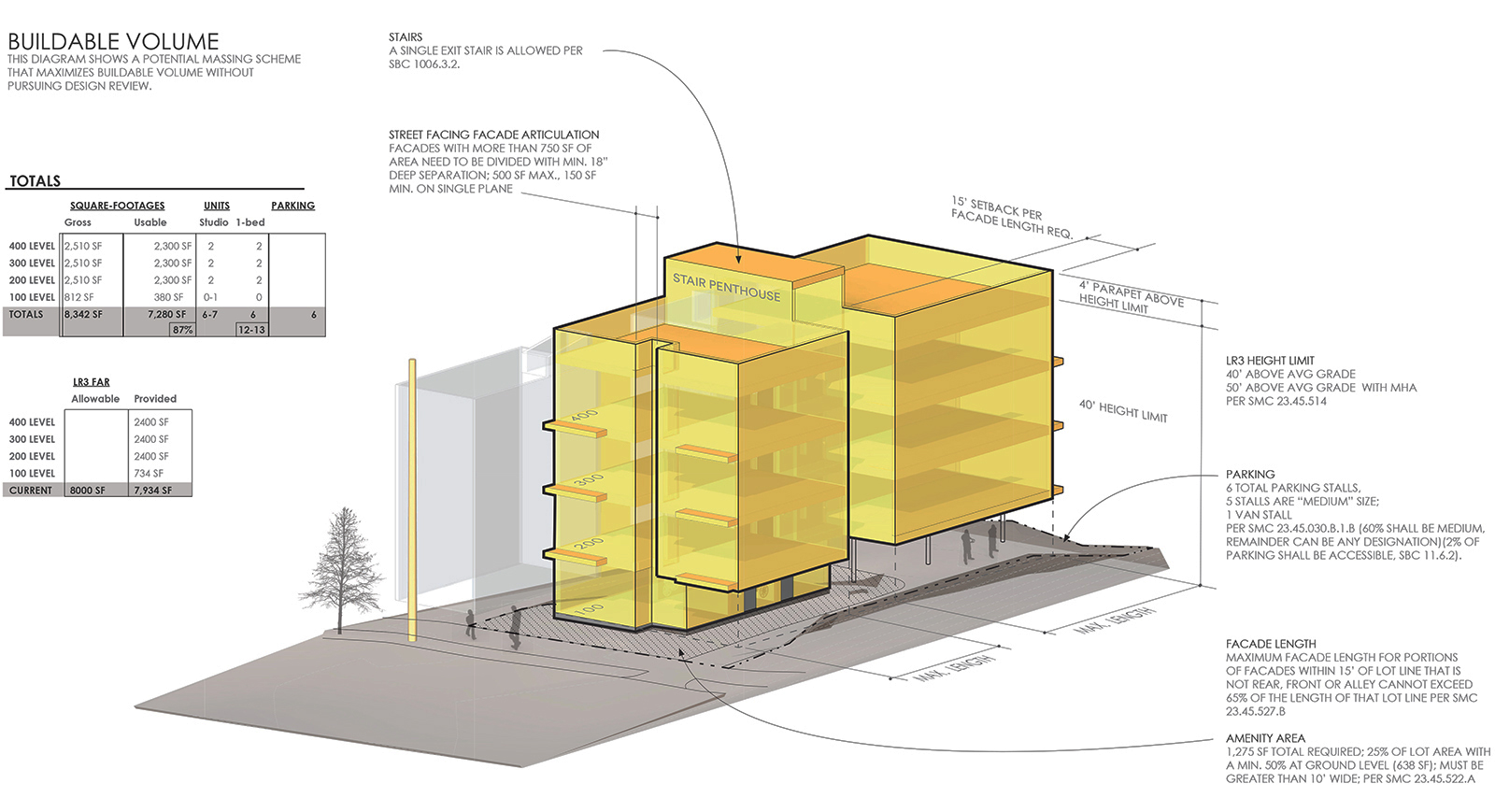

Identifying the zoning sweet spot is critical, and smaller lots that have been upzoned from a single-family residential (SFR) to a lowrise zone (LR) are generally the best candidates; better still, because they are small enough (typically around 5,000-sf), big developers aren’t competing for them, and the parcels allow more development potential than the typical homeowner knows what to do with. In Seattle, these zones are LR1, LR2, and LR3, which are commonly upzoned from the SFR zones. Once these LR parcels are identified, it’s worth taking a deep dive into the land use code to ascertain what’s possible Most jurisdictions include an area threshold that dictates the extent of the design review process, and Seattle is no exception. Multi-family projects in these zones are excluded from the entire early community outreach and design review processes if the proposed project is less than 8,000–sf (per table 23.41.004). Note that for the purposes of this article we’re not focusing on higher density zones, as they are mostly sought after by larger, well-funded developers and investors.

MIND THE FINE PRINT

The footnotes in any land use code are important to the extent that the wrong directive can annul an entire permit strategy if it’s not understood correctly. For instance, in Seattle’s thorny land use code, a footnote pertaining to the 8,000-sf area threshold (footnote #3 of 23.41.004) calls for design review if the parcel was rezoned from a single-family residential zone to an LR zone between 2017 and 2023. This is all based on an obscure Seattle City Council bill (#119057) that’s tucked away in the labyrinth of the City’s archives. There are dozens of these little land mines in any land use code.

COMBINING LOTS DEFEATS THE PURPOSE

Knowing that a Rubicon exists at a certain threshold (8,000-sf in this example) indicates that sometimes smaller is better. More often than not, land is thought to be more valuable if smaller parcels are combined to create larger projects. But the math outlined above may suggest otherwise. For example, when considering the added costs of an additional eight to ten months of a design team’s time, staggering permit fees, and a design review process that can dictate the terms of your project, two adjacent parcels, each with apartment buildings of 7,999-sf might actually be a more profitable proforma than combined parcels with one 18,000-sf apartment building.

UNDERSTAND BUILDING CODE THRESHOLDS

Keeping a building small can actually be challenging when it comes to the code. Required stairways, elevators, amenity areas, and bike parking all add square footage to a building. Here again, there are critical thresholds that must be understood to keep a multi-family building tidy, code-forming, and profitable. One key provision in the International Building Code (IBC) is the single exit stipulation documented in 1006.3.2(1), which states that a multi-family building can use a single stairway if there are no more than four units per floor. Understanding this subtle egress code plays a huge role in the design of a multi-family project, and can save tens of thousands of dollars in construction costs (stairs and elevators are expensive). It’s also something that should be planned for early in the design process.

GIVE AND TAKE

It’s important to understand that most cities encourage density, but they have to incentivize it in ways that don’t defy their own land use code. One way could be by allowing an extra floor of units by granting a building height bonus for structures of only four feet. This allowance is contingent on a partially below-grade ground floor (per SMC 23.45.514.F), which retains a more uniform building mass. Such codes have requirements and dependencies, but if used correctly, an extra floor of rentable units can be a game-changer.

LESS IS MORE

When working with the land use and building codes, it’s critical to understand features that trigger expensive, space-consuming requirements. One such item is the tempting shared roof deck on an apartment building. A roof deck is a nice feature, and it satisfies some of the code required amenity area of a project, but for accessibility reasons it automatically triggers an elevator. The expense of an elevator alone can kill the proforma of a project, and the space it requires can easily reduce a one-bedroom unit on each floor to a studio. Having run the numbers dozens of times, a roof deck is rarely worth the expense and requisite space for an elevator.

GET AHEAD OF THE PARKING

While determining the transit service area of a parcel seems like a minor detail, it actually has a significant impact on the design of a multi-family project. For example, if the adjacent street is considered a Frequent Transit Service Area, the parking requirements can change drastically—they may be cut by half. When one medium parking stall consumes 128-sf, the spatial requirements can take a sizable chunk out of the buildable ground floor area. Many other factors can have a similar effect on the parking requirements of a project, such as whether the site is located in an Urban Village or Center. The key takeaway is that a thorough study of the zoning map is not sufficient to identify the sweet spot of a project—the overlays and transit maps should also be studied.

ESTABLISH A VALUE MODEL

The criteria outlined above define the design boundaries of a project; added to this are required setbacks, regulated site proportions, and dozens of other code provisions that all multi-family projects are subject to. Knowing the total square footage, the number of units per floor, and the likelihood of a single stairway allows the design team to reverse engineer the blueprint, and establish a basic floor plan and building mass.

SOLVE THE EQUATION FIRST, THEN ADD THE POETICS

The design process described above may diminish the romantic idea of architect as a creative genius, water-coloring grand designs based purely on imagination and artistry. Those days are long gone. Architecture is a profession of research, code analysis, math, and creative problem solving. The land use code, building code, energy code, accessibility code, fire code, mechanical code, project logistics and environmentally critical areas need to be resolved first, and then the poetics of design may come into play. In addition to having a working knowledge of how all of these codes work independently and together, an architect should also have a basic understanding of a proforma.

TAKE ON COMMUNITY OUTREACH AS A GOOD NEIGHBOR, NOT AS A CODE REQUIREMENT

The strategies above aim to eliminate costly and time-consuming aspects of project permitting, and while they don’t require checking the Early Community Outreach box, we’re huge proponents of this activity. The gesture of reaching out to neighbors and community members to communicate project goals, listen to concerns, and incorporate feedback is an important step of any project, and we have every intention of always engaging this process. But when it’s just another form to complete and submit to the City, it feels inauthentic and hasty. Good design and development teams simply do this anyway, just not on a city’s clock and billing rate.

SUMMARY

Of course, these methods aren’t for every building or every city. They are strategies for small projects that need to be extremely efficient because they are being permitted in highly bureaucratic jurisdictions. These strategies are intended for cities like Seattle and San Francisco, where the permit requirements are now so expensive, time-consuming, and nerve-racking that they jeopardize the very housing these cities so desperately need.

It should also be clear that these strategies rely on a new breed of architect—ones who thrive on research and gathering, creative problem solving, and good old-fashioned math. Architects today need to have periphery vision that considers much more than just the project itself. While items like environmentally critical areas, exceptional trees, or street improvements don’t necessarily kill projects, if they’re not planned for they can add unnecessary time and cost to the permitting process.

In this new era of design, producing a better ratio of value to cost (of time and money) depends heavily on pushing back against excessive permitting requirements, and finding new ways through the maze. Our built environment depends on it.

Cheers from team BUILD