If you’re an architect, developer, or design consultant working in the Pacific Northwest, you’re well aware of the increasing difficulty of entitling and permitting multi-family projects with the City of Seattle. The process has become so time-consuming, complicated, and expensive, that an alarming threshold is about to be crossed. If this trajectory continues, small, local developers will no longer be able to mitigate the cost and timeline of entitling and permitting neighborhood-scale projects. Similarly, small architecture firms are being threatened by the bandwidth, time, and resources required of a robust entitlement and permitting process.

If you work for the Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections (SDCI), or an associated City agency, you’re well aware of a different, but related, set of challenges. A steadily increasing number of permit submittals over the past decade has led to an overwhelming queue of projects awaiting permit review.

In order for the City to maintain a fair and regulated review process, projects now wait months in the queue before the permit review process even begins. Additionally, the litigious climate of the building industry ensures that a permit reviewer’s evaluation must be guided by the constantly evolving land-use and building codes. More than ever, a permit reviewer’s responsibilities include fielding calls and emails from anxious design professionals, coordinating with frustrated property owners who are paying expensive mortgages while a project sits idle, dealing with communities conflicted about urban growth, and a land-use code that becomes more arcane by the day. On top of this, the SDCI recently implemented a new, City-mandated online submittal system and digital project portal that, while adequate for the most part, does not function effectively —they simply were not ready for prime time. As a result, a permit reviewer’s role now requires them to be part politician, part lawyer, part web-tech, and part complaint desk. Simultaneous to fielding all of these distractions, it is expected that City reviewers have the bandwidth and focus to fairly evaluate a permit submittal for construction. Needless to say, it’s expensive and time-consuming for a building department to succeed at this balancing act; in order to accomplish all of the tasks outlined above, plan reviewers at the City of Seattle currently bill $384 per hour.

This situation is having very real and tangible effects on Seattle; namely that new, small buildings and the firms that create them are now on the endangered species list. The challenges and cost impacts are blind to project scale—that is, small multi-family and mixed-used projects require nearly the same professional time and energy (and entitlement budget) as large-scale projects. At the same time, these smaller projects don’t have the value to cover the increasing costs of entry—they simply don’t contain enough housing units.

The bigger the project, the more housing units are included to absorb the cost impacts, and as a basic function of scale, the equation ends up fostering mega-projects. It’s only these huge-scale developments that can offset the disproportionate City fees and protracted permit schedules, while still creating a project that pencils out in the end. More than ever, these are multi-block projects generated by big development companies and designed by corporate architecture firms. Despite Seattle’s intention to create contextual, neighborhood-scale projects, the permitting process is actually disincentivizing them and imperiling the design firms who can do them well. In our experience, the smaller-scaled projects, highly desired by Seattleites, are generally locally-owned and -developed by working people committed to the long-term viability of the city. They are *not* the Real Estate Investment Trusts (REIT) that are required to maximize shareholder return. All too often these large-scale REIT-driven projects litter the city and appear to maximize investment return at the cost of civic and street experience.

To better understand the expense and time required to entitle and permit a multi-family project in Seattle, we’ve broken the process down step-by-step.

THE THRESHOLD

If a multi-family or mixed-use project in Seattle exceeds 15,000-square feet of gross area (or 8,000-square feet if the property sits adjacent to a single-family residential zone), the City requires a 6-step entitlement and permitting process (as a point of reference, a building in this category could be as small as 25 apartment units). Each step must be submitted, reviewed, and approved before the next step can begin, further protracting the entitlement and permitting timeline.

STEP 1 – PROJECT NUMBER, PAR & PRE-SUBMITTAL MEETING

In the City of Seattle, the permitting process officially begins with a preliminary application submitted to the SDCI to establish a project number and to request a Pre-Application Report (PAR)—this is the City’s quick fact-check of a property. Approximately six to eight weeks after the preliminary application is submitted, the City issues the PAR, which documents the property characteristics, critical areas, groups required to be involved with developing the property, and other considerations for permitting. Once the PAR has been received, a pre-submittal meeting should be scheduled to review issues pertaining to land-use codes and public utilities. These meetings are typically six to eight weeks out and are generally helpful to developers and architects, as they provide the undivided attention of a land-use planner who answers questions, clarifies code provisions, and is an accountable reviewer and contact moving forward. In addition, an Early Design Guidance (EDG) pre-submittal meeting is required, which demands that the design team record and submit meeting minutes to the SDCI for review, approval, and issuance. Unfortunately, this first step has already consumed three months of a project schedule.

STEP 2 – ECO

The Early Community Outreach (ECO) program was recently introduced to the entitlement and permitting process by the Department of Neighborhoods (DoN), and, according to the DoN website, it aims to accomplish the following:

“The purpose of the community outreach plan is to identify the outreach methods an applicant will use to establish a dialogue with nearby communities early in the development process in order to share information about the project, better understand the local context, and hear community interests and concerns related to the project. The plan shall include printed, electronic/digital, and in-person outreach methods.”

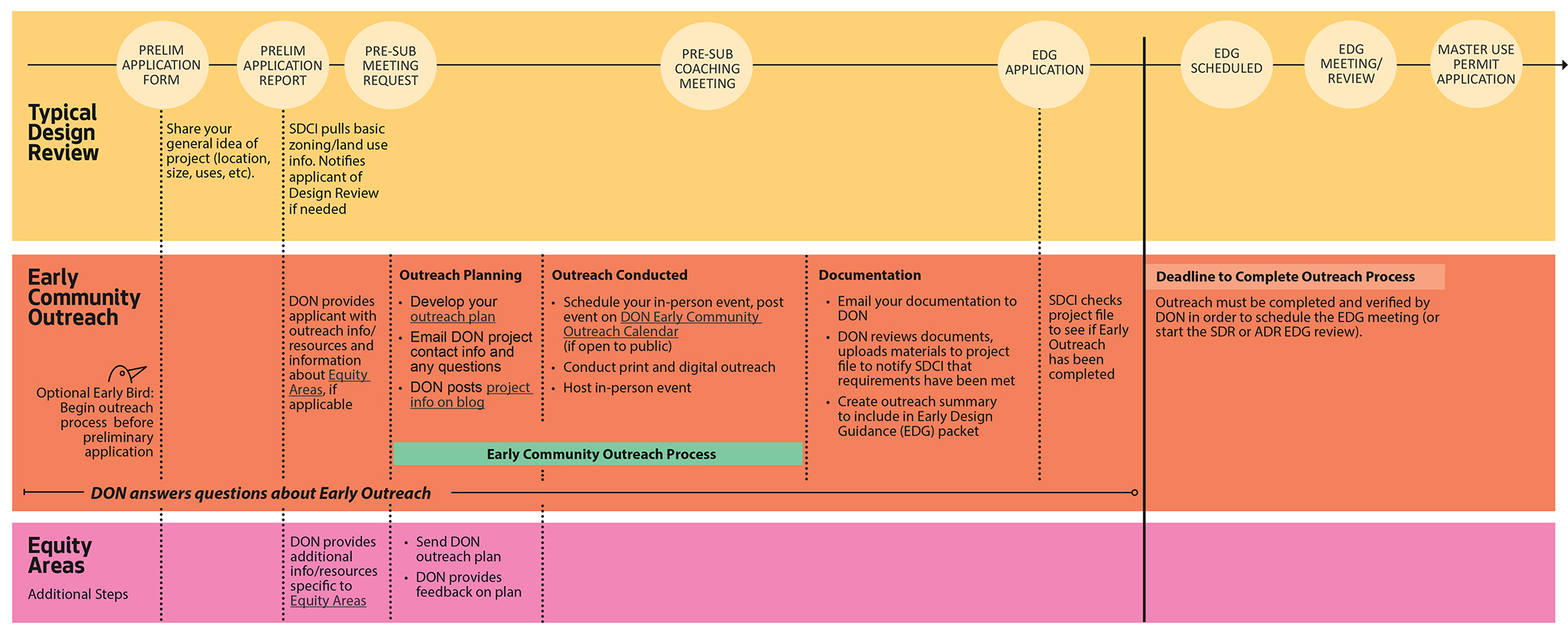

Further specifics about the three components of the ECO (print, digital, in person) may be found here, and this flowchart also helps understand the process.

While the intentions of the ECO are admirable, the guidelines are also controversial, as it’s the type of community outreach that thoughtful developers and architects have been doing all along. Formalizing this step into red-tape, checklists and approvals dehumanizes the effort and shifts the design team’s time away from outreach and design, to working through the bureaucracy. In truth, it feels like many architects are being punished because a handful of negligent developers and design teams have continually failed to meet a baseline diligence of community engagement. Whether the architect incorporates this package into their workflow or hires a community outreach consultant, the process adds a minimum of one month to the schedule.

In fairness to the primary City agencies tasked with implementing ECO — namely, SDCI and DoN — our firm has gone through ECO on three projects and each agency provided their support smoothly. ECO equates to approximately 40-60 hours of non-billable time for us, as there isn’t room in our client fee structure to compensate us for this, but at least the time spent wasn’t exacerbated by administrative issues.

STEP 3 – DESIGN REVIEW

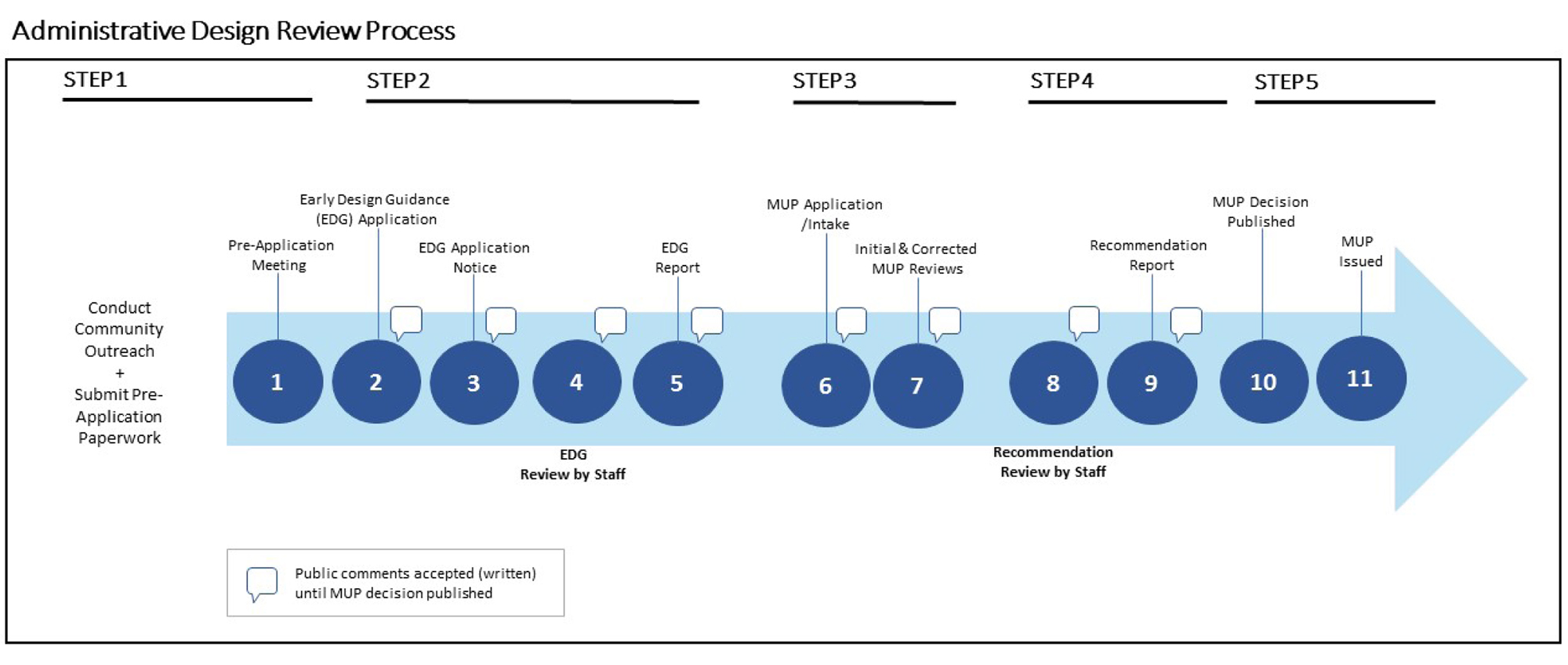

As a required component of a new development, Design Review is separated into three paths: Full Design Review (FDR), Administrative Design Review (ADR), and Streamlined Design Review (SDR). We’ll focus here on the ADR, as it most commonly applies to small, neighborhood buildings (per SMC 23.41.004, Table A, if you want to get nerdy). The City has three principal objectives for the design review process:

1. To encourage excellence in site planning and design of projects such that they enhance the character of the City.

2. To provide flexibility in the application of development standards.

3. To improve communication and participation among developers, neighbors, and the City early in the design and siting of new development.

The ADR process requires the creation of an EDG package, the primary component of which is a hefty graphic-design exercise resulting in a code-intensive book of approximately 70 pages, which provides an analysis of the site and context, and documentation of the site strategies of a proposed project. To demonstrate that the design team has considered multiple design options, the EDG package requires three designs, including one preferred and two alternatives, with each scheme developed to the point of siting, massing, and circulation.

It should be no mystery that a good architectural team recognizes the most appropriate design and bolsters the preferred scheme by creating less desirable alternatives. While we applaud the philosophy of exploring multiple schemes throughout the design process, we have to admit that the requirement to fully document and present alternative schemes strikes us as wasteful. For architects with bachelor’s and master’s degrees, professional licenses, and other accreditation, it also feels like going back and taking a second-year undergraduate design studio. It’s mind-numbing work during a critical design phase of a project. It also costs months of time and tens of thousands of dollars. Though we understand that this exercise holds negligent developers and mediocre architects accountable to a sensible design process. Here’s the City’s flowchart:

STEP 4 – DESIGN RECOMMENDATION

Once step 3 is complete, the SDCI issues corrections and/or modifications to the design review package, which is then incorporated into an additional graphic design exercise focusing on one scheme (most likely the preferred scheme). As a response to the EDG decision, this design recommendation package includes rendered elevations with material callouts, landscape plans, signage drawings, and details as specific as exterior lighting design. All of this is assembled and submitted, and the clock continues to tick.

STEP 5 – MUP

The Master Use Permit (MUP) is a required land use review for substantial developments, and most architects would agree that this portion of the process is useful and necessary. The MUP set includes preliminary consultant drawings, survey and landscape plans, for example, and results in a thick set of full-size architectural drawings. Additional components, such as a review of the State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA), a historic analysis (if existing structures are on site), geotechnical reports, environmental critical area exemption forms, and arborist reports are also included with the submittal. Different from the exercises outlined in steps 3 and 4, the drawings generated for the MUP are useful for future development of the project. Two to three months are required to generate a MUP submittal, and depending on the complexity, the SDCI review process can take anywhere from three to six months, plus time for corrections and responses. Once the MUP has been submitted, reviewed and approved, the architect has cleared the land use portion of the entitlement process, and can now focus on the building permit documents and application.

STEP 6 – BUILDING PERMIT

The building permit application requires a host of documents, with the most important being the drawing set, which covers everything from code compliance and consultant drawings (structural, civil, HVAC, etc), to plans, elevations, sections, and assembly details. Additional drawing packages, like street improvement plans, are also typically requested. The submittal includes a small mountain of paperwork, including structural, energy and stormwater calculations, green-factor documentation, statements of financial responsibility, and checklists, lots of checklists. The City of Seattle’s building permit review of a multi-family project takes four to six months, with additional time for corrections and responses.

Oftentimes, the development team will choose to administer MUP and building permit processes concurrently, as running them sequentially adds ½ year to the process. The risk in doing this is that a design impact that may fall out of the MUP process could significantly influence the building form and building permit documents. This could then instigate a chain reaction, which requires significant rework of the building permit documents and review process. But, as you’re probably sensing, most development teams feel compelled to take the risk to avoid another half year of carrying project costs.

APPROVED BUILDING PERMIT

By this point, the process has consumed 15-18 months, and the approved permit-set may seem like a rippling mirage within the permitting desert, but the day will come when the construction adventure will begin. While the intake submittal and hourly review fees are staggering, developers and architects jump at the chance to pay the final issuance fee to put the permitting process largely behind them.

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS

Keep in mind, this six-step procedure pertains only to entitlement and permitting; while some of the steps overlap, the entire design process with the client, constructability and budgeting with the general contractor, and financing with the bank are each a separate package that require horsepower, time, and fee.

THE PERSPECTIVE

We have a great amount of respect for the plan reviewers at the City of Seattle, the individuals sitting on design review boards throughout the city, and the numerous neighborhood groups; they work hard, are well-intentioned, and desire a functional, aesthetically pleasing community that’s thoughtful, inclusive, diverse, and sustainable.

We get it. Entitlement and permitting measures like those outlined above have been put in place by the City because negligent developers and hack architects are turning cities into thoughtless and short-lived built environments. Unfortunately, they penalize everyone, especially the small developers and small architecture firms that can’t absorb the resultant escalating costs. The ultimate winners are the big developers and architecture firms with entire departments dedicated to chewing through the bureaucracy and red tape. It’s not just that many of these requirements are a poor use of time, it’s that small developers and small architecture firms simply can’t afford the financial obligation and bandwidth they demand. Modest buildings don’t pencil out anymore. Neighborhood-scale projects and small firms are in serious jeopardy.

We’ll get into some possible solutions with another post, but we wanted to map out the entitlement and permitting process for multi-family projects as a departure point for this important discussion in Seattle (and likely many other cities across the U.S.).

Cheers from team BUILD