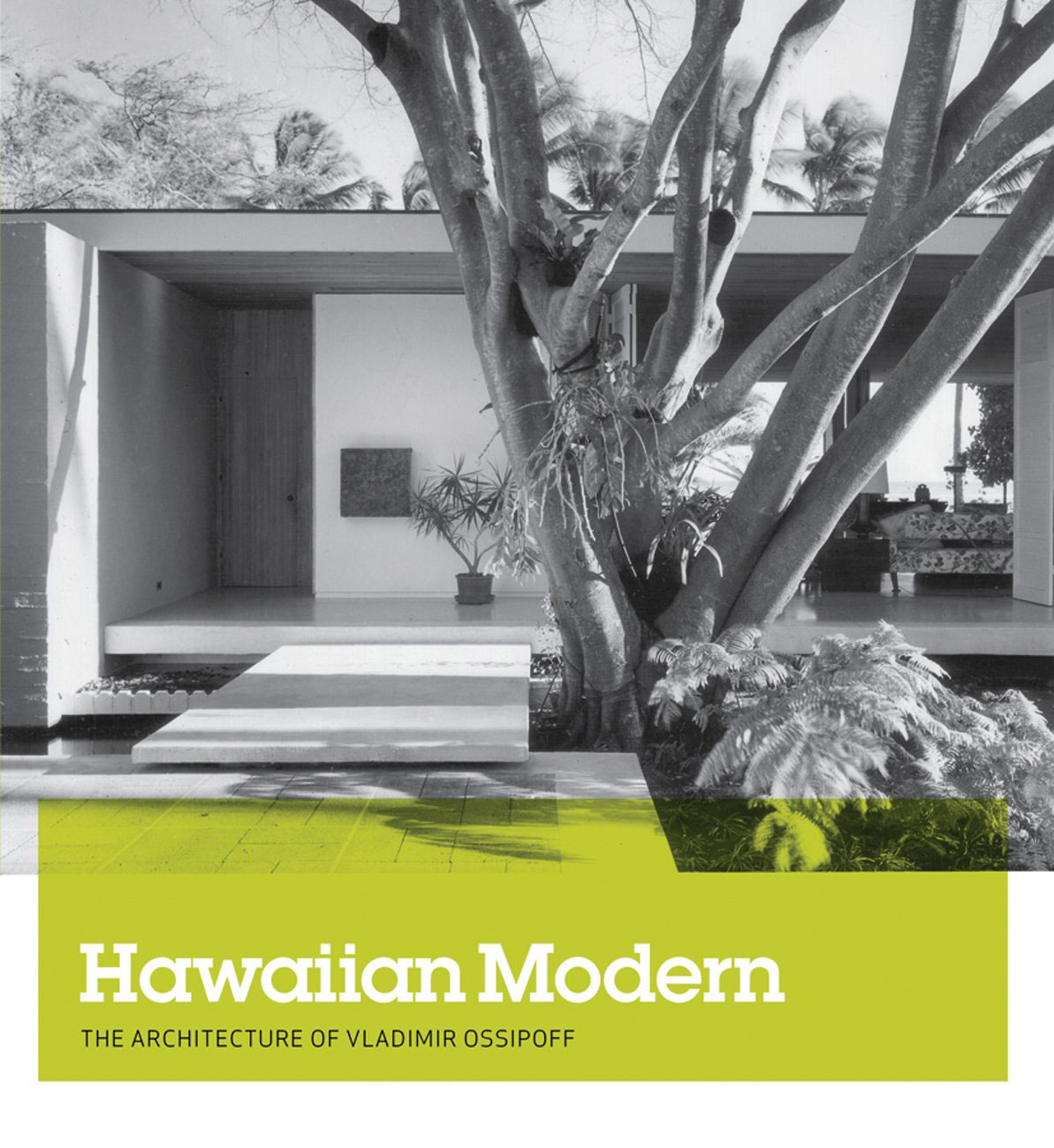

[Photo by Mariko Reed]

Over the holidays, we’ll be traveling to Oahu to meet up with Dean Sakamoto, lead researcher, exhibition curator and editor of Hawaiian Modern, the Architecture of Vladimir Ossipoff. It’s a rare opportunity to discuss the work of a seminal mid-century modern architect whose work continues to inspire designers throughout the world. Ossipoff’s work originally captured our attention for its primal sensibilities. Everything from the exposed framing of his residences to the relationship between building and landscape is mindful and relatable. At the same time, none of it is overly designed or precious. Regardless of scale, the works in Ossipoff’s portfolio are functionally graceful, rejecting sensationalism for honesty and refined practicality.

In preparation for our visit, we’ve been brushing up on Ossipoff’s projects and ideas. Admittedly, we’re astonished at the relevancy of this Russian-born, Japanese-raised, Berkeley-educated, Hawaiian-practicing architect, whose primary works are now a lifetime removed. In fact, the more layers of his work we uncover, the more applicable his thoughts and endeavors seem to our current design environment. A quote from Ossipoff illustrates his comprehensive understanding of the architecture profession:

“An architect has to be a bit of a sociologist, lawyer, and psychologist. He has to know human nature.”

In addition to covering some of his seminal projects, today’s post discusses five characteristics of Ossipoff’s work that are more important than ever to the success of contemporary architecture.

Environmental Responsiveness

Long before the sustainability movement became a household conversation and the unfortunate greenwashing industry that has followed, Ossipoff was designing houses and structures with an intelligent response to environmental factors. Free from all the green gadgetry so popular with sustainability today, Ossipoff’s designs incorporated timeless methods such as deep overhangs to cool the interiors, wood louvers to allow natural ventilation, and post and beam lanais to draw the breeze. The Goodsill house incorporates many of these features and there’s a very nice portfolio of images of the house at Modernist Architecture by Architectural Photographer Darren Bradley.

[Photo by Darren Bradley]

Simple, Rational Structures

In an age of sensationalism and overly complicated designs, it’s refreshing to see great works of architecture executed without pretense. Ossipoff’s designs look exactly like what they’re doing. The necessary structure of a building is often celebrated as the primary driver of the architectural forms while repetitive elements develop a harmony within the design. Because of its expressed grid of columns and slabs, the University of Hawai’i Administration Building is one of the clearest examples of these qualities as captured by photographer and author Robert Wenkam whose images appear throughout Hawaiian Modern.

[Photo by Robert Wenkam]

Lack of Pretense

There is a raw, almost naked quality about how a column meets a beam and how a beam meets the roof in Ossipoff’s work. While some may find this design aesthetic to lack sophistication, we find it unpretentious and honest. Such an authentic expression of shelter is both fundamental to the nature of architecture and graceful to the inhabitant. Nowhere is this more apparent than the William H. Hill House in Kona.

[Photo by Robert Wenkam]

Accepting the Nature of Nature

There is a certain elegance with which Ossipoff’s work has weathered over time and it would seem as though the weathering process was a consideration of the design all along. The projects appear all the more complete once the materials have patinaed and the vegetation has fully grown in. His forethought and patience brings the architecture and landscape into one harmonious design concept. Even within the construction process, Ossipoff allowed space for the imperfections of nature as indicated in the Laupahoehoe School, where rounded boulders gathered along the nearby shoreline replaced much of the aggregate in the concrete. The aesthetic result of this process must have involved significant variables up until the formwork was removed. The completed project would suggest that this leap of faith paid off as the school embraces the form factor of the indigenous materials and creates a work that belongs to the place.

[Photo by Darren Bradley]

Knowing When to Break the Rules

Like any great master architect, Ossipoff spent his career crafting a set of rules that aligned with his values, worked with his palette of materials, and flourished in the tropical environment. Also like any master, he knew when and how to break out of his own rules. The simple gable roofs of so many of his residences set up the perfect architectural boundaries from which to then depart, as seen in the Liljestrand House with its clever nod to asymmetry.

[Photo via Honolulu Magazine]

There is much to learn from Ossipoff’s work and while his projects apply to a distinct philosophy in a specific place, his lessons ought to carry more gravity in the design world than ever. Ossipoff noted in the early 1960s that he carried on a “War on Ugliness,” a struggle to counter what he felt was poor architectural design and unrestricted development. We’d go as far to say that the work of Ossipoff is a mindful oasis in a built environment growing more prone to thoughtless design. We’re looking forward to experiencing the work in person and continuing the battle.

Cheers from Team BUILD