[Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles, photo via A.Zahner Co.]

The technological advancements available to architects in today’s design and construction industries are truly awesome. Advanced modeling software now allows for the design of highly complex and irregular geometries while digital fabrication processes enable metals to be produced and assembled at large scales in nearly seamless forms. In parallel with these developments, digital prototyping is establishing a direct relationship between design exploration and physical production. All of this is allowing designers to take a quantum leap in how they work and the architectural end results that they produce.

With significant advancements and possibilities, however, come misuses and exploitation, and the architectural world is no exception. Perhaps as a consequence of the technologies mentioned above, we’re seeing some disturbing trends in the design world and it’s precisely the type of situation that may haunt architecture for generations to come.

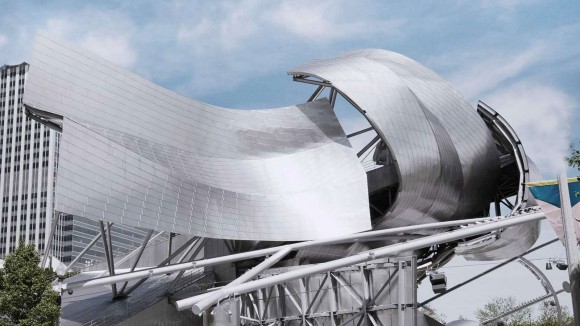

[J. Pritzker Pavilion in Chicago, Photo via Wikipedia]

The worst offenders share an alarming amount of similarities. There’s usually a plain but perfectly functional building designed to keep the rain out and accommodate the architectural function within. The envelope of the building is then punctured dozens (sometimes hundreds) of times with armatures that extend out to support an additional structural framework which then supports a second, highly decorative skin. While functionally redundant, these ornamental, outermost skins rarely have anything to do with the inner building. More often than not, these outer skins tend to be extremely stylized, albeit permanent, masks.

What’s important to point out is the distinction between an authentic building envelope and the ornamental embellishments of an architectural mask. The former is practical, cost-effective, and uses resources sensibly. While the latter can be highly fashionable, completely impractical, and a hog of resources. Authentic building envelopes require the design team to work with discipline and efficiency while ornamental masks encourage spectacle at the cost of sensibility and proficiency.

[J. Pritzker Pavilion in Chicago, Photo via Architizer]

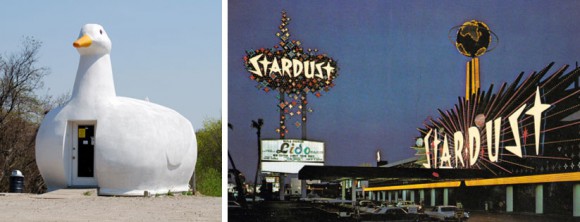

Architects Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown may have laid the foundation for this conversation better than anyone in their enduring text Learning from Las Vegas. Though the book predates the technologies mentioned above, most architects would be quick to point out that back in the 1970s Venturi and Scott Brown made a very relevant distinction between the duck, a building that itself is the symbol of its purpose, and the decorated shed, a generic structure with applied ornamental flourishes and/or signage to communicate its purpose. Their examples focus on two primary building types: The duck-shaped structures that housed egg vendors in Eastern Long Island are the textbook example of a building that looks like what it’s doing (hence the term). In contrast to this are decorated sheds — the generic Las Vegas shed-like casinos popular in the 1960s and 70s, whose purpose could only be identified by the addition of ornamental signage.

[Left image via nowpraepailin, Right image via Tumblr]

The duck vs. decorated shed study is a significant departure point for this conversation because so many prominent buildings in the built environment borrow the worst from each category. Name brand architecture seems to be trending toward an unfortunate application of exterior decoration in order to disguise generic sheds as faux ducks.

These architectures introduce a level of complexity that is simply mind-boggling. The amount of secondary framework alone is often a building’s worth of steel. The armature penetrations within the inner envelope guarantee a lifetime of maintenance chasing down leaks. Just looking at these structural systems with an excessive number of connections is head-spinning. And, adding insult to injury, the design team often boasts that every panel on the skin is uniquely different, as if that were the ultimate accomplishment as architects. These same architects regale the press with all of the design challenges they had to overcome on the project, but what they fail to mention is that the majority of these challenges were self-inflicted. After overcoming all of these challenges, the finished products still rarely achieve a simple message of the building’s actual purpose (to say nothing of the cost escalations).

[Biomuseo in Panama under construction, photo via bcipanama]

The original examples cited by Venturi and Scott Brown are timid compared to the current architectural predicament. The architectures concerning us most aren’t cute roadside vendors or ornamental casino signs isolated to the Las Vegas strip, but massive civic works spread throughout the world costing tens and hundreds of millions of dollars to construct. Each is a permanent fixture of our built-environment, and together they set the bar in the architecture world, and proceed to shape the public perception of “modern architecture.”

Despite the advances in design and construction, the architecture profession has created a complicated mess. There is a very real chance that this predicament will hurt architecture moving forward, and we doubt that the disciplined architects and the general public alike are interested in being penalized for the poor decisions of those who prioritize complicated art projects over effective buildings.

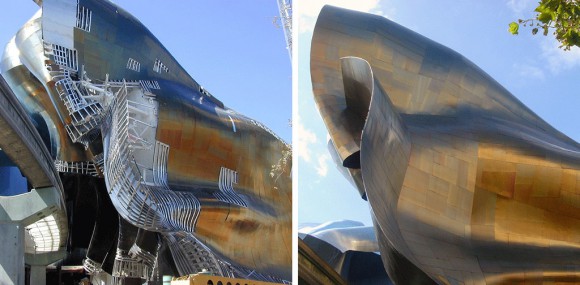

[EMP in Seattle, photo via A. Zahner Co.]

We see two ways to get the ship back on course. In spirit of technological advances and design freedoms, the architecture profession needs to bring the rigor and discipline back into the daily practice of design. If the building itself is so mediocre and uninspiring that it needs an elaborate mask to veil it, maybe the building (or architect) should be reconsidered. Architects need to regain their focus on the craft of designing and making buildings. Buildings should be smart and effective, and architects should be accountable to design sensibly and cost-effectively. Alternatively, we can stay on the current path of highly embellished decorated faux duck-sheds but we need to establish a new distinction, if for no other reason than to protect the rational design out there. The faux duck-sheds aren’t really architecture and they shouldn’t be designated as such. Instead, they are artistic sculptures built around and on top of architecture. If the artistic sculpture can’t be untangled from the architecture physically, they should at least be untangled intellectually.

[Biomuseo in Panama, photo via inparkmagazine]

How we talk about these projects shifts the perception of these projects accordingly. The general public needs to understand the implications of creating a sculpture in addition to a building, and professionals need to understand why a project like the J. Pritzker Pavilion came in 558% over the proposed cost. The technological advances that are allowing architects to explore ideas and implement new construction methods are extraordinary, but architects need to understand that just because you can do something, doesn’t mean you should. It’s rarely the most effective solution.

Cheers from Team BUILD