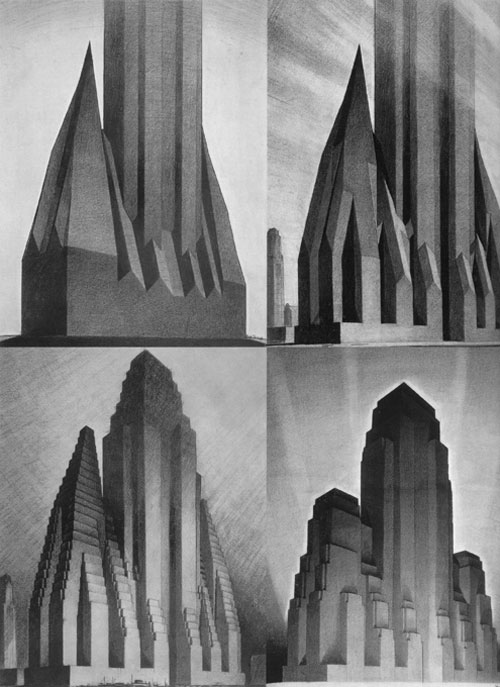

[Renderings by Hugh Ferriss]

Working on a substantial architecture project requires the gathering and analysis of a great deal of information. This information is found in documents like the International Building Code and city municipal codes; subsequently the process can lead to an overwhelming amount of data for any sizeable project. Such data involves everything from setbacks and height limits, all the way down to the required dimensions of a handrail. At face value, this information can seem awfully dull, but there is also a beauty in crunching through the raw data. Approached with the right mindset, there is poetry in the process.

Years ago, when we started taking on more complicated projects, we employed a philosophy that we’ve stuck to ever since; it makes the analysis more productive and appealing. We let the data drive the design.

It’s an idea that was popularized by two Manhattan architects who applied this type of thinking nearly a century ago. Wikipedia has a few things to say on the matter:

In 1916, New York City had passed landmark zoning laws that regulated and limited the mass of buildings according to a formula. The reason was to counteract the tendency for buildings to occupy the whole of their lot and go straight up as far as was possible. Since many architects were not sure exactly what these laws meant for their designs, in 1922 the skyscraper architect Harvey Wiley Corbett commissioned Hugh Ferriss to draw a series of four step-by-step perspectives demonstrating the architectural consequences of the zoning law. These four drawings would later be used in his 1929 book “The Metropolis of Tomorrow”.

In 1916, New York City had passed landmark zoning laws that regulated and limited the mass of buildings according to a formula. The reason was to counteract the tendency for buildings to occupy the whole of their lot and go straight up as far as was possible. Since many architects were not sure exactly what these laws meant for their designs, in 1922 the skyscraper architect Harvey Wiley Corbett commissioned Hugh Ferriss to draw a series of four step-by-step perspectives demonstrating the architectural consequences of the zoning law. These four drawings would later be used in his 1929 book “The Metropolis of Tomorrow”.

[Renderings by Hugh Ferriss]

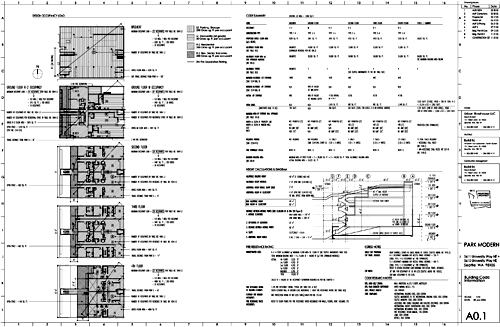

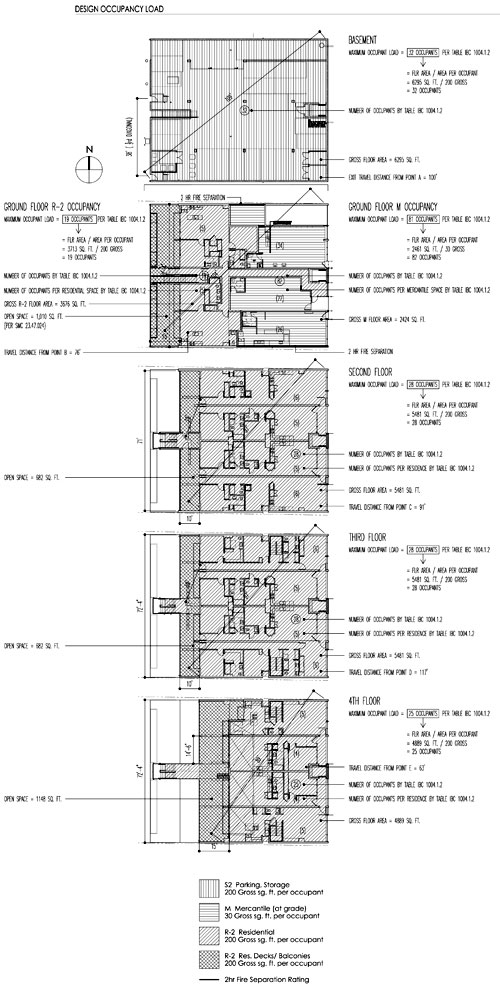

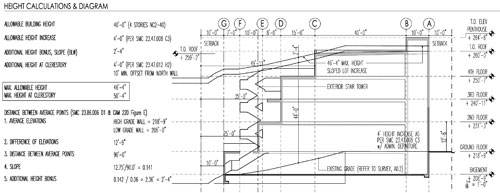

The work of Corbett and Ferriss has been infectious since we first eyed the renderings back in school. In the initial phase of a project, we sort through the codes less like architects and more like scientists. It is the codes themselves that block out the building mass and lay the groundwork for possibilities within the design. For a project as complicated as the Park Modern mixed use building we dedicated an entire page of the construction document set to interpreting the code (larger version here). It may very well be our favorite drawing that we’ve ever done.

The Park Modern drawings include series of diagrams documenting our code summary, interpreting design occupancy loads and calculating maximum heights, etc. Boring stuff, right? Wrong, at least not to us -these are the basic building blocks of the design. We took pleasure in putting these diagrams and analyses together because they became the DNA of the eventual design.

You might think that such a dry application of building codes would lead to the same answer over and over again -and therein lies the contradiction and the beauty. The more thoroughly an architect examines and interprets the code, the more clever the translation. The more clever the translation the more possibilities open up.

Clear and concise diagrams alone begin to communicate an architectural language. Our 2D diagram studies often evolve into 3D massing studies, which later become the architecture.

We take this philosophy as far as it will go. As the process continues into design development and construction documents, more and more of the design is informed by our architectural eye –but the basic translation is never lost.

This translation becomes an architecture of reason; there is a rationale for each move that is made. Looking at the built environment and being able to understand the design is one of the greatest pleasures of being architects and builders. Whether it’s the building code, physics or a client’s needs, the ability of an architect to translate words and ideas into physical form is at the root of good design.

[Photo by Chase Jarvis]