[Image by Sasaki]

In the winter of 2017, BUILD sat down with Rebecca Barnes and Kristine Kenney at the University of Washington in Seattle to discuss the dynamic developments on UW’s campus, designing and planning universities now and in the future, and what Seattle can learn from Boston during this time of major growth. Part 2 of the interview can be read here.

Rebecca Barnes, FAIA, was the university architect and vice provost for Campus Planning at UW until 2018. Throughout her career, Barnes has worked in roles such as director of planning for the City of Seattle, director of strategic growth at Brown University, and chief planner in Boston during the “Big Dig,” a megaproject that rerouted Interstate 93 underground through the city and redirected interstate traffic through a new Boston Harbor tunnel.

Kristine Kenney, ASLA, is the university landscape architect and director of campus design and planning at UW. Equipped with vast experience in campus planning in the private sector on the East Coast as well as in Seattle, for the past 18 years Kenney has been shaping the campus environment at the university.

BUILD: There’s been a boom of UW-developed housing in the University District over the last several years. What sparked this growth?

Rebecca Barnes: A decade ago, UW Housing and Food Services (HFS, a university auxiliary service) developed a master plan for a student housing village that included a grocery store, restaurants, and fitness and conference centers strategically located to increase on-campus student housing. At the time, only 17-percent of students lived in university-managed properties. With the university’s student body growing and its housing stock aging, HFS re-envisioned housing with contemporary facilities and support services.

Initially, HFS planned to renovate and expand existing housing in West and North Campus, but analysis showed they could economically achieve a better product with new construction. The resulting buildings are more tuned to the times. The buildings in West Campus were designed in phases—the first four by Mahlum, followed by a five-building complex by Feildon Clegg Bradley with Ankrom Moisan, and a three-building collection by Mithun, with GGN Landscape Architects designing most of the landscape. North Campus development is underway now, with design work by Philadelphia-based architect Kieran Timberlake and landscape architect OLIN, a well-knit team working with the university to reshape the northeast corner of Central Campus.

Kristine Kenney: The first phase of the new housing—the four buildings designed by Mahlum with landscape design by GGN—was transformative. Primarily university-owned parking lots and single-family houses, that area previously felt very unsafe. The design team broadened the sidewalks, providing generous public space, and created a series of open areas, the most significant featuring the majestic elm tree, granting a sense of relief within the density. These changes introduced a crossroads at Brooklyn and Campus Parkway, which was a catalyst for change in the University District.

[Elm Hall by Mahlum]

Are these housing entities financially self-contained or do they help fund the university’s academic work?

RB: HFS is self-sufficient and manages its own internal pro forma using some construction funds loaned from the university, with approval by the Board of Regents, which is a serious commitment of resources to student housing by the school.

How do you design for the classroom of the future, especially thinking about online education?

RB: Everything used to happen in lecture halls; now classes may take place in halls, online, or in interactive classroom settings, all within the same course. We’ve formed an advisory committee, including faculty and staff, to look at future classroom development in West Campus. It’s headed by Vikram Jandhyala, vice president for Innovation at UW and the head of CoMotion, which brings together industry and academic research to generate ideas and products for the marketplace. Faculty and support staff will be talking with people in industry—whether it’s computer science, health science, or arts and science—about what kind of spaces they each need.

As planners, how do you stake out ground for the future?

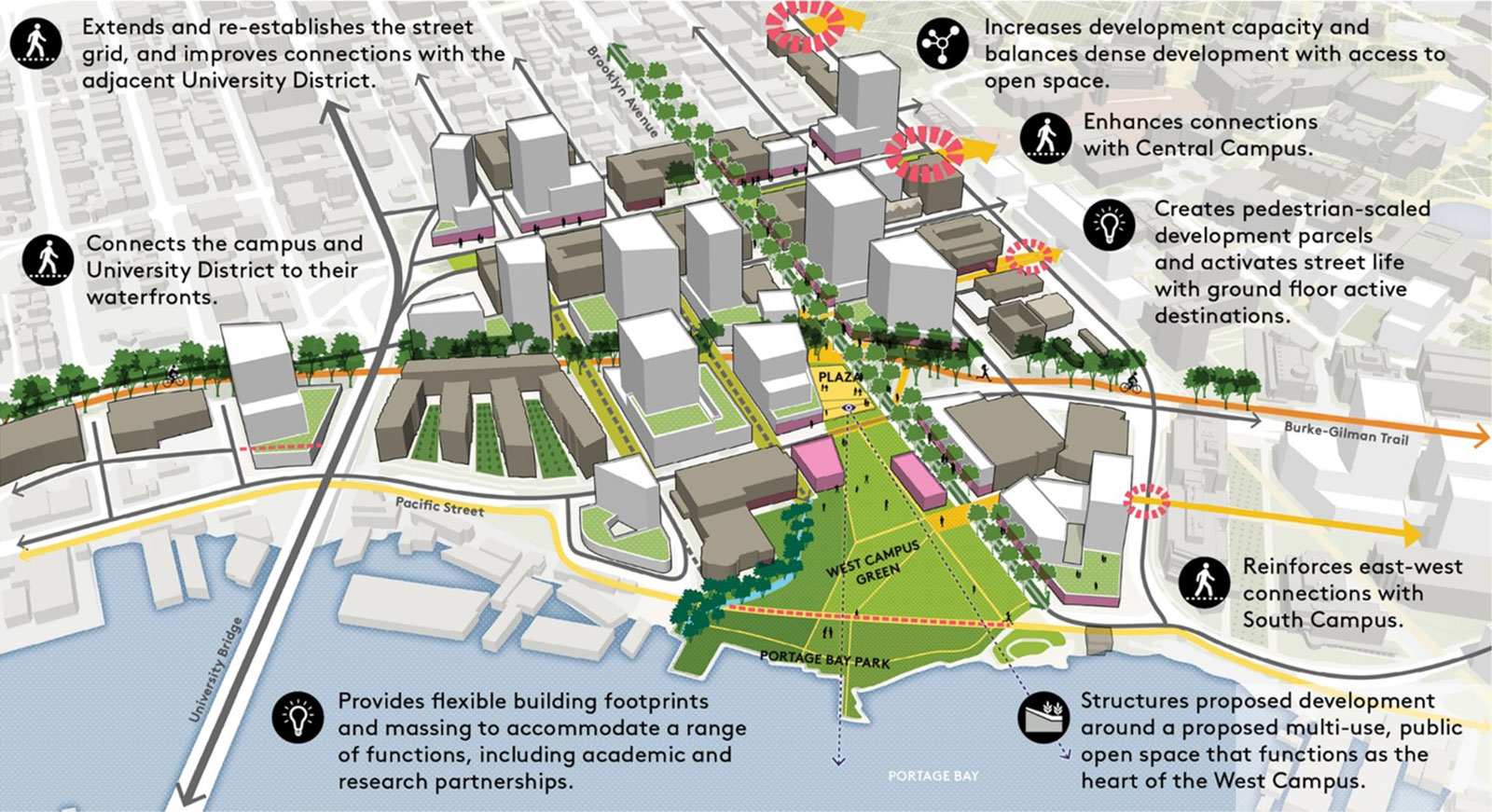

RB: The common wisdom is flexibility, which applies to everything from furnishings to technology to space. This flexibility takes its cues from the warehouses on Seattle’s waterfront, which were built as simple frame-structures with large windows to maximize daylight. These buildings can be reutilized in numerous ways over a long period of time. Things change, and we have the most to gain from the simplest structures. We’re thinking of everything from classroom design to building design to campus design in this way.

Half of our growth over the next 20 years will occur in West Campus, which is already urban and well served by infrastructure. Also, the light rail will continue to be transformative. Soon it will directly serve West Campus, connecting the area to Husky Stadium, SeaTac, Northgate, and Downtown. The U-District can now truly develop as one of Seattle’s urban centers.

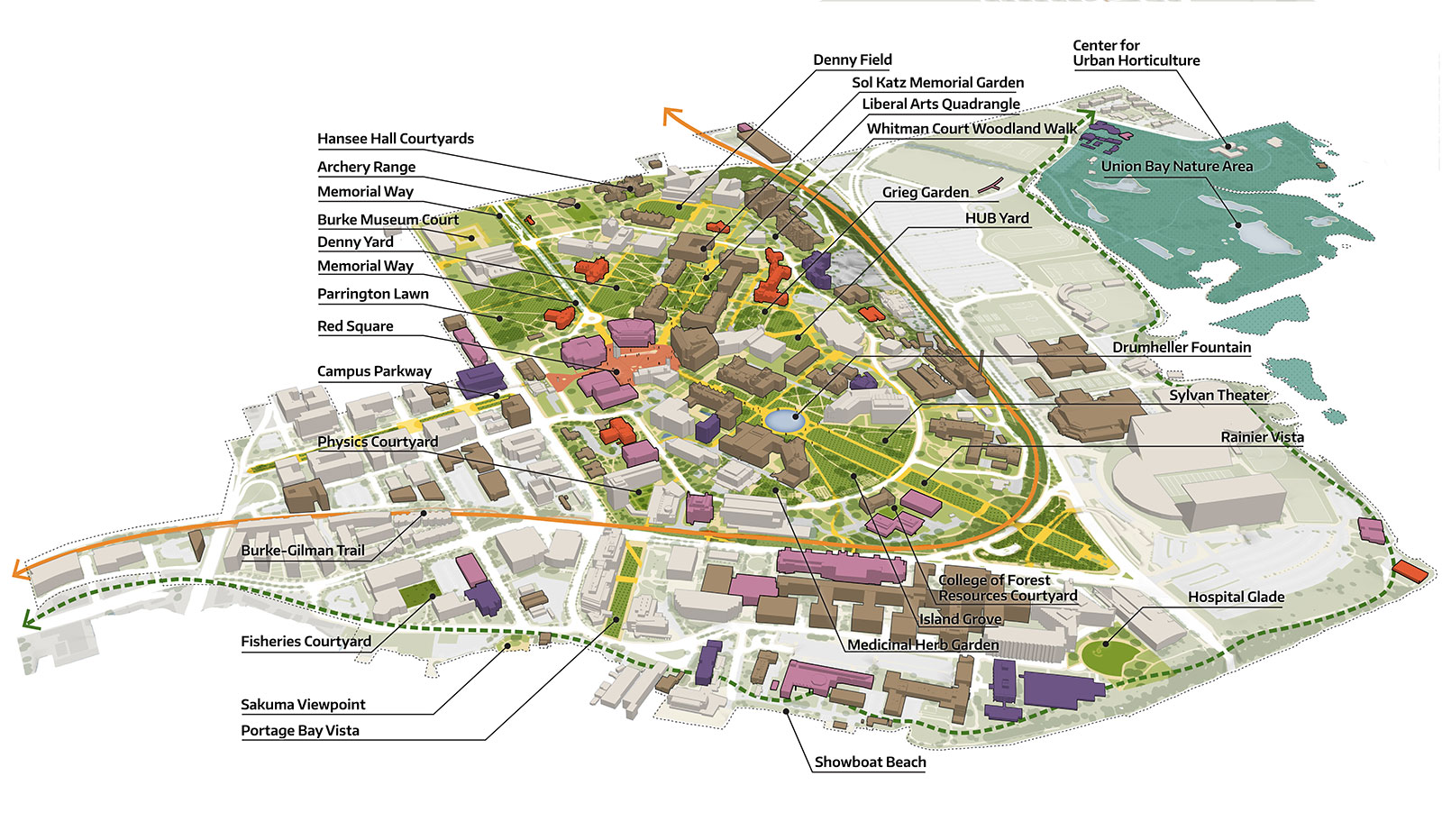

KK: The campus’s core is the traditional, historic environment most people imagine when they think of the university. Future development is proposed mostly outside of that, but for development within the core, we’re identifying ways to preserve and protect the campus’s history. When introducing new buildings into the core, we honor the existing buildings and experiences through scale, the relationship of structures to the surrounding landscapes, and by ensuring the landscape creates a seamless experience and environment throughout. We’re creating the history of tomorrow right now, which West Campus exemplifies. In 100 years, someone will look at these new spaces in the same way we’re looking at the historic core today.

[1915 revised general plan]

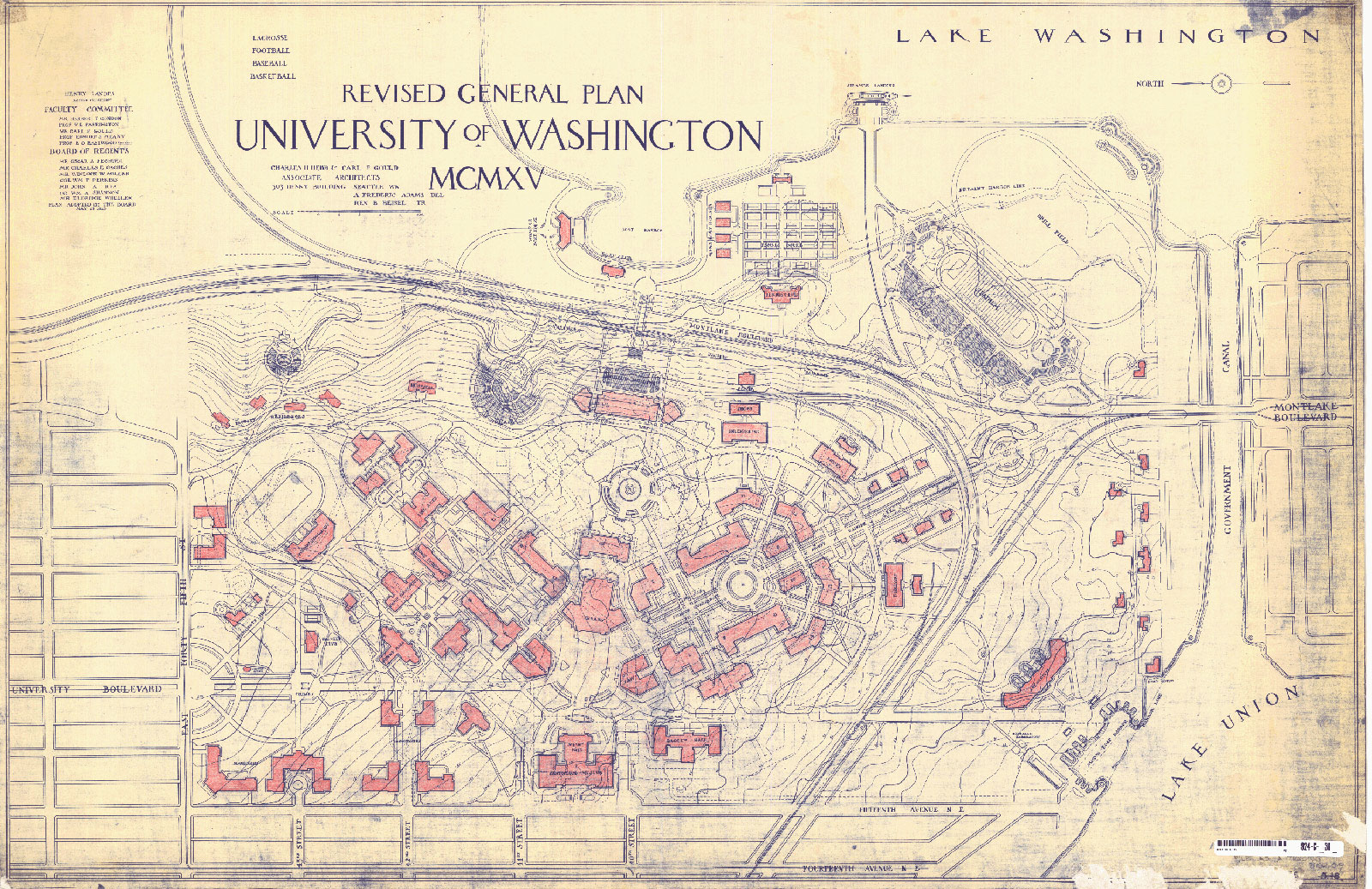

That raises an interesting point. Looking back at the original Olmsted Plan for the campus, is there anything in the plan’s DNA that provides a roadmap for future development?

KK: Rainier Vista was created by the Olmsted Brothers in 1909. It linked the campus to Mt. Rainier 60 miles away. To reach outward and connect the university’s landscape to its regional context when most campuses were focused inward is an incredible, memorable vision.

While the university’s layout is often attributed to Olmsted, credit should really be given to Bebb and Gould, who established the framework for subsequent growth through the Regents Plan of 1915. They integrated Rainier Vista’s legacy and reinforced additional axes, including the Quad and Memorial Way, which all radiate from the space in front of Suzzallo Library, now known as Red Square, which our data has revealed is the true heart of the campus. The Bebb and Gould plan also expanded upon the concept of Rainier Vista, extending the virtual boundaries of the campus outward, while offering semi-enclosed arrangements that terminate within the university’s boundaries, creating strong connections within the campus.

We continue to reinforce these connections today. For example, the North Campus Housing development at the east end of the Quad axis will sustain a student village in the woods at the edge of Denny Field.

[North Campus Housing by Kieran Timberlake, photo by Bruce Damonte]

Rebecca, as the former chief planner for the City of Boston, what would you say Seattle should learn from Boston’s Big Dig?

RB: There have been numerous delegations from Seattle to Boston over the years to learn from the Big Dig. Cities learn from each other and the seeds of that are evident here. Seattle has been thinking large-scale, which matters, along with tending effectively to local impacts, the quality of design thinking and expression, and a commitment to actively programming the new public realm. The public realm needs a management plan for its maintenance, operations, and to develop a wide range of partnerships.

Looking forward, I hope Seattle will aim high on inclusive housing goals under the Mandatory Housing Affordability program. In Boston, the mayor mandated 15% affordable housing be included in all residential projects, and that’s what happened. Seattle should aim this high or higher in our extremely hot market.

[Image by Sasaki]

Any other lessons to be learned from Boston?

RB: Keep investing in regional public transit! Boston’s transit system is in terrible condition, financially and physically, and their economy depends on it to transport people to and from work and school. We’re finally stepping up to the plate in Seattle, voting for ST3 to create a world-class regional transit system here over the next couple decades. It’s a hard lesson: the upfront money is easy, but upkeep, maintenance, and reinvestment require a whole different way of thinking. Hopefully we’ll be up for that.

KK: The livability elements I see in Boston that Seattle could borrow are public access to the waterfront and a network of public walkways through the city that provide a sense of porosity with the ability to safely walk down streets and alleys as well as through parks and even atriums of major buildings. Safe and inviting back routes allow people to interact with buildings as they pass through. There are examples of these pathways in some of Seattle’s neighborhoods, but Downtown would benefit from them as well.

Rebecca Barnes, FAIA, is the University of Washington’s university architect and vice provost for campus planning. She received a Loeb Fellowship in Advanced Environmental Design from Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, a Master of Architecture from the University of Oregon, a degree in American Civilization from Brown University, and pursued architectural studies at Boston Architectural College. She has been a board member of AIA chapters in both Seattle and Boston and has been working in urban planning and architecture for four decades.

Rebecca Barnes, FAIA, is the University of Washington’s university architect and vice provost for campus planning. She received a Loeb Fellowship in Advanced Environmental Design from Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, a Master of Architecture from the University of Oregon, a degree in American Civilization from Brown University, and pursued architectural studies at Boston Architectural College. She has been a board member of AIA chapters in both Seattle and Boston and has been working in urban planning and architecture for four decades.

Kristine Kenney, ASLA, is the University of Washington’s university landscape architect and director of campus design and planning. She received a Bachelor of Landscape Architecture from the University of Rhode Island and a Bachelor of Architecture from Roger Williams University. She was a senior associate at Mithun, an associate at Carol R. Johnson Associates, and a landscape architect with the Warwick Planning Department.

Kristine Kenney, ASLA, is the University of Washington’s university landscape architect and director of campus design and planning. She received a Bachelor of Landscape Architecture from the University of Rhode Island and a Bachelor of Architecture from Roger Williams University. She was a senior associate at Mithun, an associate at Carol R. Johnson Associates, and a landscape architect with the Warwick Planning Department.