[Photo by Andrew van Leeuwen]

In spring 2013, BUILD met with architect Stanley Saitowitz at his San Francisco studio to discuss his projects, the challenges of Modernism, and bringing good design to the people.

You and your team are true generalists, designing everything from single-family residences to skyscrapers. How is your office organized to do so?

Our work is strategic, and is modeled on an idea of architecture that relates to Mies van der Rohe. Rather than reinventing everything every time, we’re in a process of evolution and refinement. Our small office operates efficiently, and the work is well directed. We don’t do alternatives, try things on for size, or have beauty contests. It’s a studio of focused thinking, and we’re a good machine.

[Image via Saitowitz | Natoma Architects]

What is your experience working with the stringent historic preservation codes in San Francisco?

It’s the reason that we’ve been driven to look for work elsewhere. As an example, our Octavia Gateway project in San Francisco was designed in 2006, but the site remains virtually unchanged because the approval process has been stalled by discussion of minutiae. In another seven years I’ll be 70, and I just don’t have the time for these absurd situations. You don’t have so much life that you can waste seven years trying to build a 50-unit structure.

San Francisco has a way of absorbing mediocrity. A nebulous design gets much less attention here, and subsequently, there’s less resistance to it. Unfortunately, our work seems to be a lightning rod for resistance, and it’s not easy for us to get projects through the approval process, and they don’t get any better as a result of it. Everything has become so complicated and tedious; there are so many checks and balances. These processes are making it more and more impossible to do good work. I’m surprised anything decent gets built.

Where do you like to work outside of San Francisco?

Miami Beach is a great place to work because it’s a city that embraces Modern architecture, unlike San Francisco where every building is meant to be Victorian. The area has this kind of exuberant tropical Modernism, and we’re trying to work with this language and reinvigorate the tradition in a contemporary way.

[Image by Kilograph]

You’re also doing a significant amount of work in Cleveland. Can you tell us a bit about what you’re doing there?

The project is a real piece of the city’s fabric. Old Cleveland has a lot of amazing buildings, but the city has lost a third of its population, so they are mostly empty. We’re currently converting eight floors of one of these old buildings into housing, and it’s the best housing we’ve ever done because of the quality of the space. The 12-foot ceilings and massive windows make for really beautiful units; you can’t build like that anymore. Also, the work we’re doing in Cleveland for $150 per square foot would cost about $250 per square foot in San Francisco.

How did you achieve the simple elegance of the mixed-use Uptown project in Cleveland?

We compressed all of the services — including mechanical, electrical and plumbing — into a service bar in a dropped ceiling adjacent to the hallway, which runs along the spine of the building. All of the service bars line up throughout the units; the geometry is then mirrored on the opposite side of the hallway to create a double-loaded corridor. Once you move past the service bar in each of the units, there’s nothing to get in the way of the windows and high ceilings. It’s cheaper to build this way because everything is so rationalized, and it’s a simple design process.

[Photos by Rien van Rijthoven]

You once likened good architecture to Levi jeans, meaning that the right approach should have an application to the masses. Do your larger developments with repetitive plans speak to this?

Yes, many of our projects of this scale use the same service bar strategy. Our work aims to be a blank slate; it tries to be deprogrammed and indeterminate. What we try and do is make a quantity of quality. This is why I have such a dislike of most of the housing in San Francisco. The houses are based on the Victorian model, and they’re unlivable. All the rooms are the same size, and they’re all too small. They don’t represent anything about the way people live today; they’re uninhabitable.

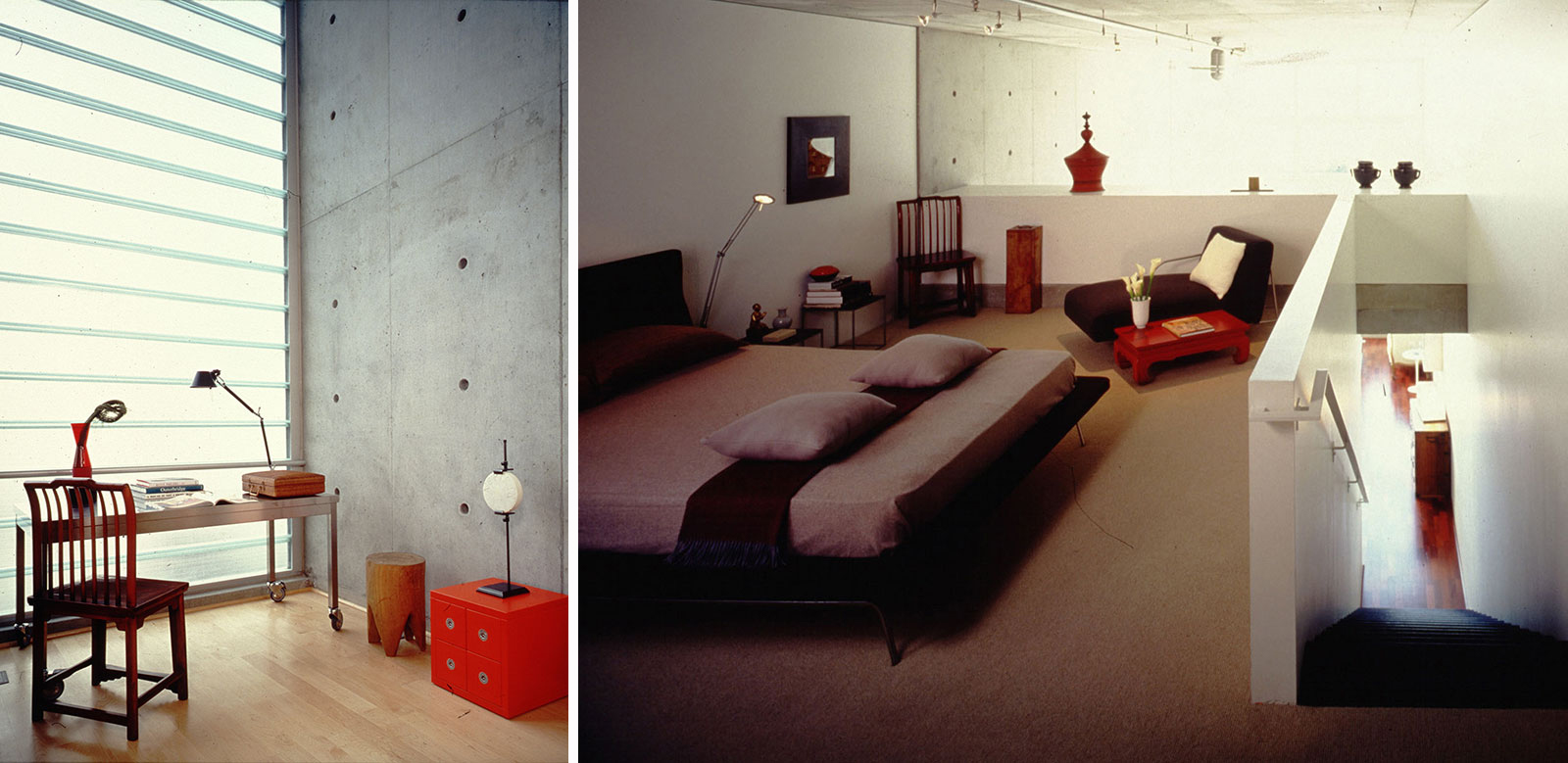

The images on your website suggest a spartan lifestyle for the inhabitants of your projects. To what degree is this simple lifestyle intended?

The German architect Ludwig Hilberseimer said that the ideal urban house should be so well designed that all you need to bring is your clothes, a chair, and table, and you could live there. In a way, that’s what we try and do with our urban housing.

[Image via Saitowitz | Natoma Architects]

Is there a point in design at which the more minimal something seems, the more complicated it actually is under the surface?

I think some architects do find that threshold, but we haven’t. I’m not a design fetishist, and I don’t care about having the best costume jewelry. I was recently at an architect’s office and they were designing door knobs. I couldn’t be bothered with that; why not use the door knobs that are already being manufactured? That’s where I think there’s a lot of waste. I have an appreciation for beautiful things, but I think machines are useful; I don’t think you have to make everything by hand. I’d rather have a bigger room than a custom-made door knob.

You believe that buildings that offer value and economy are a responsible way to build. How is the profession in general doing on this front?

I was recently in Germany and noticed the number of resources they put into the quality of architecture; they just spend more effort on their buildings. It’s a little embarrassing to see the way we build in the United States. I don’t want to make buildings cheaper; what I’m trying to figure out is how to best allocate the construction budget. I’m trying to figure out ways to optimize everything and get the most value. That is, to get the largest spaces, the best light, the most choice for the occupant. The method is pretty simple: compact all the expensive stuff, be rigorous about how it works, and have the most open-ended space for people to decide how to use it.

[Image via Saitowitz | Natoma Architects]

Is there a particular project of yours that has achieved value with little waste?

The big success for us in housing is the Yerba Buena lofts because that building was a magnate, and it was constructed for the same price as all those Dryvit buildings out there. It was built in such a way that there wasn’t any waste. With most buildings of this scale, you build a concrete structure, and then you hire people from seven or eight different trades to wrap it up. Some of these buildings use a hideous amount of materials on the façade. With Yerba Buena, we just had concrete and glass, which involved fewer trades to complete the building. This freed up more funds to put better materials into the building—we were able to use channel glass for instance. It was an exercise in figuring out how to manage resources more intelligently within the standards that exist.

[Image via Saitowitz | Natoma Architects]

Many of your projects span entire city blocks; at what point does the project require you to think like an urban planner?

As the architect, we often inherit the entire lot. The project may already be approved, the number of units and floor area ratio may be fixed, and the number of parking spots predetermined. We don’t necessarily have to be planners.

Do you consider your work to be regional?

I’m not regional in terms of wanting to be a Bay Area architect; I consider our work to be multi-regional. Our basic interest is in place, and the differences in places. In Berkeley I want to make Berkeley buildings, and in Toronto I want to make Toronto buildings.

What is your advice to architects about working with big developers?

If you can do what they want, which is to be efficient, they won’t micromanage the design (at least not the developers we work with). We have much more freedom working with developers than with single-family residential clients, and it’s much less tedious. While developers may not be directly interested in good design, they realize that the market is.

What is your advice to young architects starting their own practices?

Having built projects to show makes it easier for people to believe in your work. Having projects that people could see is what allowed me to get my start. I don’t know how a young architect would even start a practice today; it’s just so hard. I don’t see anyone going out on their own anymore.

What’s on your nightstand? What are you currently reading?

I recently finished Community and Privacy by Serge Chermayeff and Christopher Alexander, and I’m currently reading Metropolisarchitecture by Ludwig Hilberseimer. I read mostly to support my wars.

Stanley Saitowitz was born in Johannesburg, South Africa, and received his masters in architecture at the University of California, Berkeley. He has taught at numerous schools, including Berkeley, Harvard and Rice. His award-winning projects include residences, museums, libraries, wineries, synagogues and memorials. Three books have been published on his work, and he has given more than 200 public lectures.

Stanley Saitowitz was born in Johannesburg, South Africa, and received his masters in architecture at the University of California, Berkeley. He has taught at numerous schools, including Berkeley, Harvard and Rice. His award-winning projects include residences, museums, libraries, wineries, synagogues and memorials. Three books have been published on his work, and he has given more than 200 public lectures.