[Images courtesy of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum]

Last winter, BUILD met up with Ruki Ravikumar, Director of Education at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York City. They talked about the Design Museum’s role in America, a designer’s professional responsibility, and getting the light bulbs to go on.

BUILD: Tell us a bit about your training and how it dovetails with the mission of Cooper Hewitt.

Ruki Ravikumar: I have essentially had on the job training at Cooper Hewitt; my role demands that I connect with a broad range of people and cultures, which has in turn provided me with a wonderful, real time, learning environment. All of my travels, and every job I’ve ever had, even the crazy ones, have culminated in the work I’m doing now. I feel as though I’ve been practicing for my entire life to be here.

What drew me to Cooper Hewitt is its clear mission to inspire, educate and empower people through design. This is significant. I could imagine myself contributing to this mission at each level, and although education is the middle pillar, you can’t educate someone without first inspiring them—and when they are educated, they are empowered. So, these three words guide everything I do.

Given that the Cooper Hewitt is the National Design Museum, what responsibility do you and your team shoulder?

Although we believe in the value of design and why we should talk about it early in our curricula, as we travel the country and visit schools, we notice a broad lack of discernment of the subject. Given that Cooper Hewitt is America’s design museum, part of our responsibility is to cultivate awareness. As a museum, we have embraced the mission to spread design literacy before going into deeper provocations on what the future of design could be. Once opportunities for exposure to design have been established, we can help people interpret the world they live in and develop a design mindset. Everyone has creative potential, and, in some sense, design is the most relatable of all fields.

You’ve mentioned that you like to use specific objects within Cooper Hewitt’s collection to engage with people. What’s an example of this?

There is a piece in the collection called Bioimplantable Device for Reconstructive Shoulder Surgery (England, 2004); the material feels like a lacey doily, and it looks similar to a snowflake. When most people look at it, they assume it’s a historic piece of embroidery; but, when we reveal that it’s a medical device, they immediately want to know more. We explain that it connects the traditions of textiles with modern medical research, and the result is a gorgeous piece of art that is used in joint reconstructive surgery. When educators start to see this connection, they can relate; they start to talk about collaborative work, and they want all of their students to be able to make relationships between biology and art. This is what STEM education can do.

Which aspects of design in the United States would you most like to address with your mission?

As a museum, we’ve homed in on designers thinking about their professional responsibilities from many different angles. Inclusive design is an excellent example; we’re having such robust conversations about it and are learning that on some levels design unintentionally exiled people. We want things to be better, faster, and leaner, and as part of this pursuit we’ve created things that don’t break down easily. If the current generation is more thoughtful about what we make, why we make it, and what will happen to it when its useful life has expired, the next generation of designers will not be in the same reactive place as we are. No matter what we’re exhibiting at Cooper Hewitt, whether it’s Access+Ability or The Road Ahead: Reimagining Mobility, the common thread is about designers’ professional responsibility. Are they asking all of the right questions before they create something new?

What about the museum or the facilities do you wish more people were aware of?

The collection is digitized, so you don’t have to be in New York to access it, and there are multiple ways to explore it, such as by color, time period, culture, or country. It reinforces the notion that research is about losing yourself in something and making discoveries, rather than having a predefined idea about what you will find. It’s a tool that people don’t use enough at Cooper Hewitt.

Tell me about the Immersion Room at Cooper Hewitt.

Museums have a reputation for don’t touch and look without experiencing, but that’s not our philosophy. We have entire exhibits that are meant to be touched and interacted with in order to understand what they’re doing. The point of the Immersion Room is for people to have a highly experimental learning moment, for example, on wallpaper: visitors make drawings on digital tables, which are then duplicated, and the patterns are projected onto the walls around them. Visitors start to get the sense that a simply created swatch can become self-designed wallpaper, and it teaches about pattern and repetition in design. The result is visitors who are inspired by basic principles of design. It’s just magic when you see the light bulb go on.

In today’s world of over-the-top sensationalism, where everyone is relentlessly promoting their own brand, how do you determine who is actually going to make significant contributions to the future of design?

Every three years we assess the state of design through the Design Triennial exhibition series; we look at it through different lenses and consider where it is today and where it may be in the future. We’re currently examining the intersection between design and nature: how is design facilitating natural processes, how is design inspiring and protecting? As the curators explore the kind of work going on at this intersection, they uncover a seminal body of work. They learn about designers who are pushing the boundaries of technology and approaching problem solving in a more permanent way. Ultimately, they are thinking about how they can change an entire system.

Cooper Hewitt is known for collections and exhibits that explore nearly a quarter millennium of design and creativity. Given this depth of perspective, what observations about design might be less obvious to most of us?

Every day we rediscover something in our collection that we hadn’t thought about in a given context before. For example, as education becomes more tool-based, the separation widens between the haves and the have-nots because schools in lower income communities simply don’t have access. So, when teaching about prototyping, it was important to us to identify some very basic examples. We looked for examples of prototypes made without 3-D printers, and we’re thinking about how we could better tell this story to inspire people. We visited the work of Eva Zeisel, who developed beautiful prototypes simply by cutting paper, and her work led to the discovery of a variety of designers working on similar problems. Little of this work has been published, and now we get to incorporate this design thinking and resultant projects into the curriculum. Tools like this will allow us to get kids in lower-income communities to the same educational place as those with more advanced tools. I’m constantly looking for better ways to connect people to the breadth of the stories we have at the museum.

In our awards-saturated design world, what separates Cooper Hewitt’s National Design Awards?

What makes it different is that the jury is comprised of an interdisciplinary panel of designers, so candidates are truly being assessed by peers in a broad range of fields. These awards are the highest honor because the work grows out of a cross-disciplinary approach.

What is important to understand about helping architects and designers to craft their legacies in the design world?

I think what Cooper Hewitt does well is to collect a multi-layered story of designers and their work. As an educator, it’s important to understand that the two don’t have to go together; they’re not of a piece. When talking about the power of inclusive design, we don’t address the work of a single designer but instead reference every designer who has touched the problem. I think this is true of any good storyteller: they’re never just telling one story, but nested plots and various sub-stories. This is also true of Cooper Hewitt’s collection.

Which exhibit at the Cooper Hewitt are you most proud of and why?

I get excited about all of the exhibits because they each tell different stories, and they each will speak to a different demographic. We recently had an exhibit called Tablescapes: Designs for Dining, and in the beginning I was a little confused about how to bring in teenagers from underserved areas of the city and get them excited about an opulent French centerpiece. Would I actually be working against myself because they won’t relate to it? But, when we told them that at a certain point in time dining was theater, and then showed them the minimalism of Joe Doucet’s work and how he was inspired by a light bulb, we saw them connect to the exhibition and draw comparisons. It’s exciting for me to consider the range of stories an exhibition may tell and who they will speak to and to then lure those people into the museum.

Any favorite hidden gems in Manhattan?

The Big 9 sculpture at 9 West 57th Street by Ivan Chermayeff is one of my favorites. As a graphic design student, anything I first saw as a tiny picture in my textbooks I always wanted to see in person, and this was at the top of my list.

What does the design world need more of?

A sense of humanity.

What is the one book that all designers should have on their shelf?

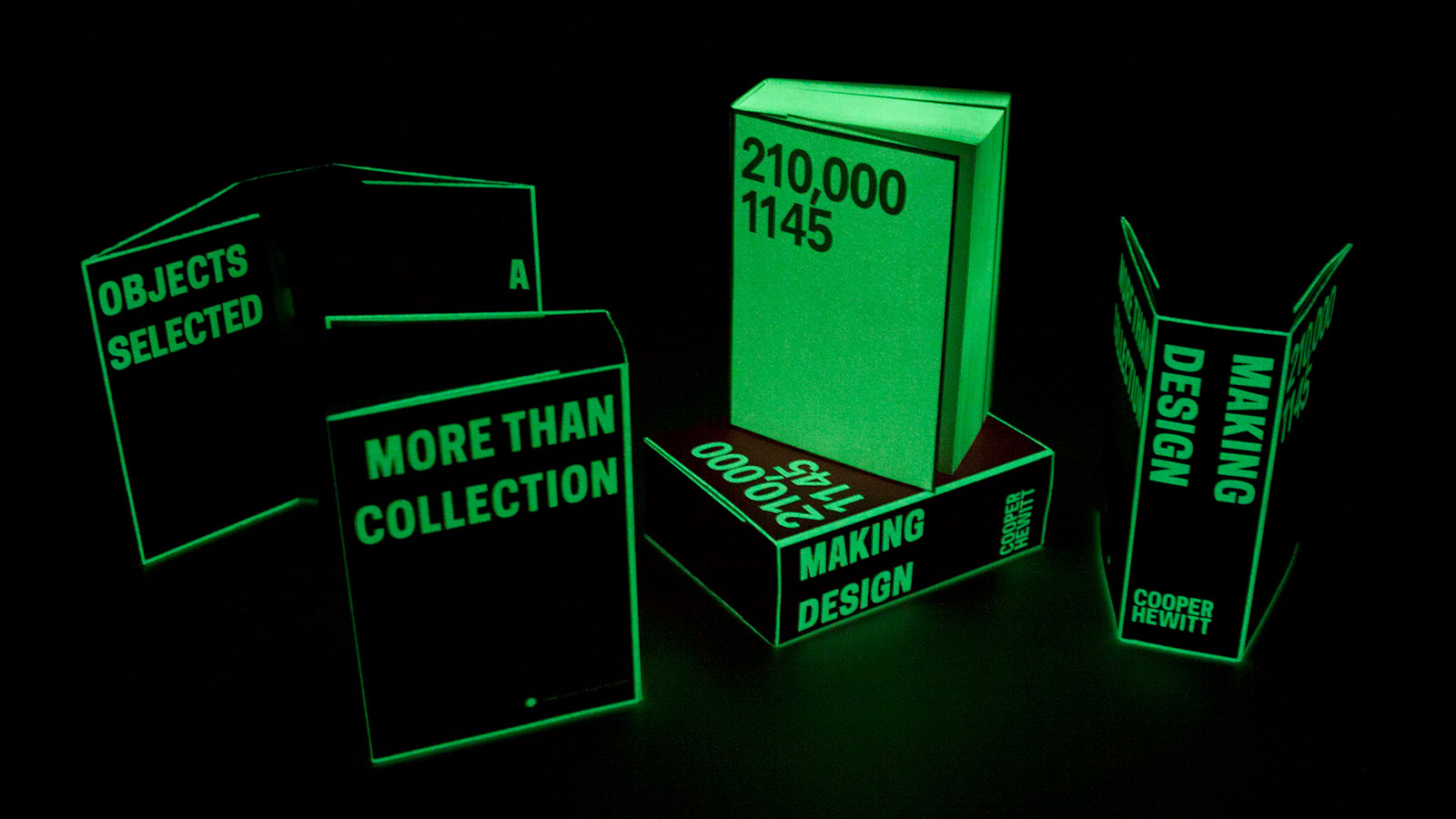

Making Design—which illustrates Cooper Hewitt’s more than 210,000 objects. It’s a fantastic collection, and when I find myself stuck trying to explain something to somebody, a quick flip through the manual makes me think about different designs over time. It’s a tremendous source of inspiration for designers, and it also glows in the dark.

Ruki Ravikumar is the director of education at Cooper Hewitt. Ruki serves as the principal leader responsible for expanding Cooper Hewitt’s educational outreach initiatives, including the National Design Awards, Design in the Classroom National, and the National High School Design Competition, both nationally and globally. Ruki holds a bachelor’s degree in the history of fine art and drawing and painting from the University of Madras and a Master of Fine Art in Graphic Design from Iowa State University.

Ruki Ravikumar is the director of education at Cooper Hewitt. Ruki serves as the principal leader responsible for expanding Cooper Hewitt’s educational outreach initiatives, including the National Design Awards, Design in the Classroom National, and the National High School Design Competition, both nationally and globally. Ruki holds a bachelor’s degree in the history of fine art and drawing and painting from the University of Madras and a Master of Fine Art in Graphic Design from Iowa State University.

BUILD llc is an industrious architecture firm in Seattle run by Kevin Eckert, Andrew van Leeuwen, Bart Gibson, and Carey Moran. The firm’s work focuses on effective, sustainable, and sensible design. BUILD llc operates an architectural office, contributes to ARCADE with an ongoing interview series, and is most known for their cultural leadership on the BUILD Blog.