[Photo: Elizabeth Gear]

Last spring, BUILD met with architect, author, and Harvard professor Farshid Moussavi at her office in London’s tidy Pimlico neighborhood. We discussed design competitions, the nature of analysis, and how a small firm can take on big work. We also touched on open-source architecture and the balance of a successful firm. Part 1 of the interview can be read here.

As head of Farshid Moussavi Architecture, you lead the firm in dozens of international projects of all scales and functions, you’ve authored several books, and you hold a professorship at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. What are the life management skills you’ve mastered in order to succeed at all of this?

I’ve learned to understand the virtue of this position. I teach one semester per year, and intentionally refrain from teaching the next semester. When I’m teaching I think about architecture through the lens of academia. When I’m not teaching, the balance shifts and I’m thinking about architecture through the lens of practice. When I’m teaching, I’m responding to work in the evenings, but I also find that I think with a fresher mind away from the office. Both roles run together but with different levels of intensity.

There is a sacrifice that comes with having two jobs. I socialize less and I have less time for myself. But it allows me to look at things from a broader perspective and taking time off from one is good for the other.

Your website lists over 25 design competitions that you’ve submitted entries for over the years. How do you balance the time and financial commitments of competition work with the obligations of your client based projects?

The commissioned projects have a dedicated team and they are not distracted by the competition work in the office. In our office, if you’re working on a competition that wins, you typically stay with that project. My time gets divided between projects and competitions.

We enjoy the competitions because they are a way to think more ambitiously to begin with, whereas with a commissioned project, the ambition is built over time. Ideally both types of projects should be equally as interesting in the end, but the processes to get there are very different.

In 1995, you and your now ex-husband and former business partner Alejandro Zaera-Polo won the design competition for the international port terminal in Yokohama, which was completed in 2002. How do you take a small design studio from winning its first large commission to designing something at the scale of a port?

When we won the competition, there were literally just the two of us, so there was a big learning curve. At the time I think the client was probably very nervous with a $200 million project and a design team that had never built a project and never worked in Japan. It took time for the project to move forward, but it afforded us the opportunity to get set up. Sometimes, out of sheer necessity, you just get your act together. Even when the project was in full production, our team was never more than eight people. Projects are more effective when they are done with teams as small as they need to be and no more. We worked in a Japanese style, which is a day and a half of work, and I must admit it was very long hours at the time. Maybe if it was a more conventional work regime, the process would require a larger design team. We had a small local firm to work with in Japan and we borrowed two people from that firm to help with the work.

[Photo: Satoru Mishima]

What has changed about building trust in clients and convincing them that you have what it takes to complete challenging projects?

Building trust in clients is an ongoing issue for architects. Curiously, having gone through the Port of Yokohama process and having completed the terminal successfully, we still have to convince clients that we can accomplish projects of this scale. The people building the future of housing and offices are incredibly young — they’re in their mid to late twenties and I’m hoping they’ll be more tuned in to what actually makes a smart practice. I think a leaner office is ultimately sharper in any organization.

The idea of ‘function’ merits an entire category on your website. Explain the importance of the FUNCTIONLAB.

We decided that it would be interesting to see what other people would do with this approach to function. So we set up this virtual think-tank where we invite other architects and non-architects to develop these pamphlets on a particular topic. Hopefully a conversation develops over time.

Given that many of your designs are heavily influenced by analysis, is there a danger that the process will generate architecture that is overly diagrammatic?

While architecture is embroiled in data like dimensions, weights, and material properties, we don’t look at it like abstract numbers. Rather than looking at data as numbers, we look at how things are mapped in space. There are many aspects of data that inform a design decision. This extends beyond metrics like dimensions and weights and may take into consideration how something will be delivered to the construction site. Ultimately, this mapping of information is about finding points of compromise or priority.

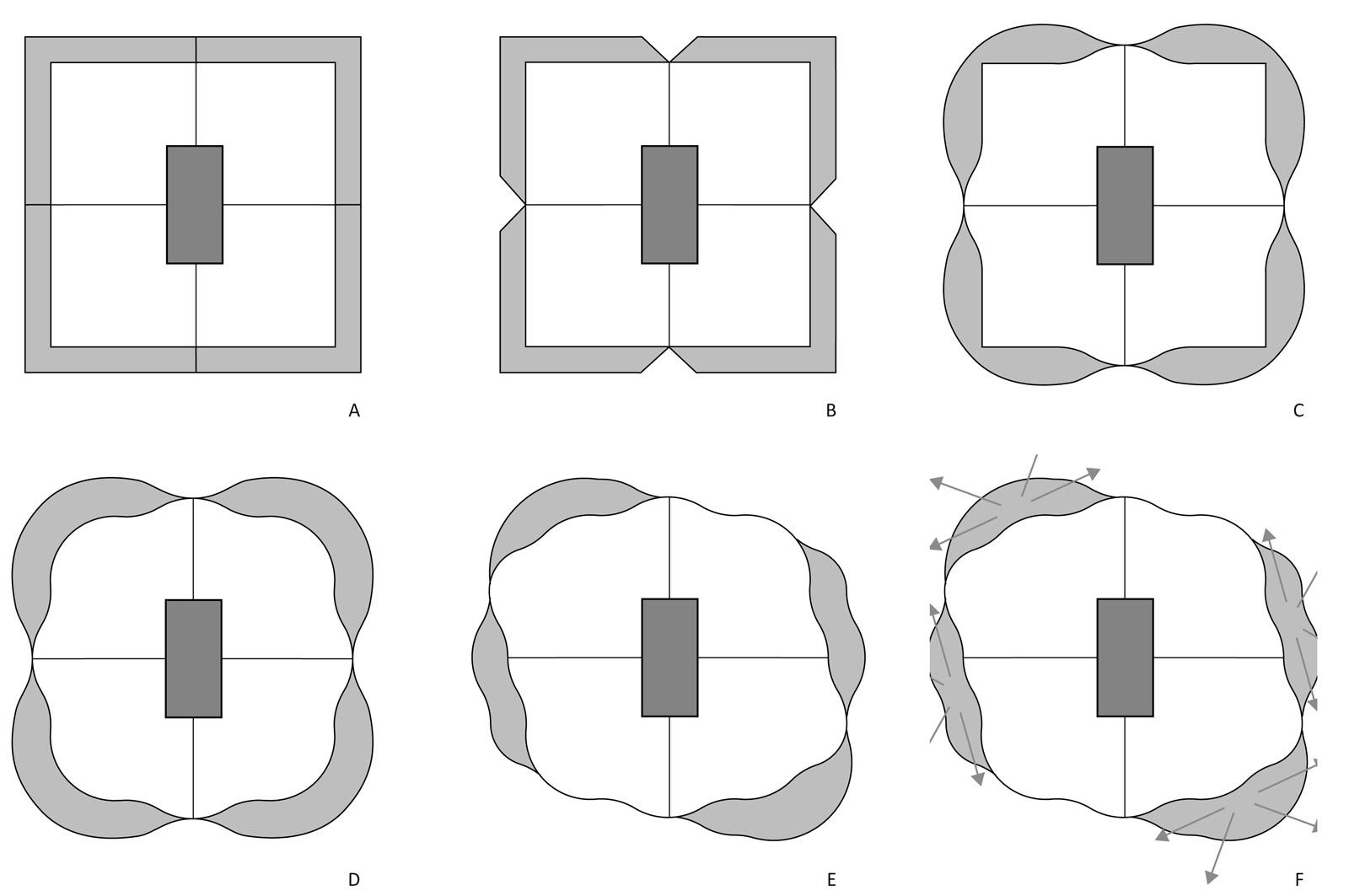

[Image: FMA]

With so much of your work based in competitions, how do you best communicate the research of your designs to a jury without drowning them in data?

I think it’s quite difficult to have that level of clarity and that amount of data in the beginning when you present your scheme on a competition project. You don’t have the time and you don’t have the other players on board yet to analyze a project to a high level of detail. You don’t know all of the drivers yet. The time working with consultants, manufacturers, and suppliers is absolutely necessary for a project to become rich in data. At the competition phase of a project, we typically just have some ideas that start to guide the project.

You’ve stated that style, which represents authorship or the overzealous protection of an architect’s ideas, inhibits the migration and circulation of ideas. Do you see architecture going in the direction of open-source design in the future?

I think it’s already open source. Anyone working in an architectural office today is constantly going to architecture websites for information and inspiration. Architects are being fed all day by work not of their own, but by others. We used to go and travel to see buildings and now we see them on the screen. We’ve become very aware of what is possible and who has done what.

What lessons have you brought forward from your experiences working in offices such as the Office for Metropolitan Architecture and the Renzo Piano Building Workshop?

Working for these firms, I learned just as much about office structure as architecture itself. When I went to work for Renzo Piano, it was very much like a workshop, almost like an extension of school with teams and pinups and crits. In addition to developing a project’s design, we would build a detail of a project at one to one scale. It was an extremely friendly office, almost like a family where twice a day the entire office would get coffee together at a café. Offices are a delicate dynamic and it only takes a couple of people who are not good team players to upset the balance. It’s good to be ambitious but not to be competitive.

When I got to OMA, it was a bigger office and Rem was often out traveling for projects. People would compete for his attention, which made it impossible for others to succeed. I learned to be more sensitive to the employees’ point of view through these experiences. It’s good to have worked for other people to see the office structure from different perspectives.

[Photo: FMA]

Farshid Moussavi is an architect, principal of Farshid Moussavi Architecture (FMA) and professor in practice of architecture at Harvard University Graduate School of Design. She was previously cofounder of the London-based Foreign Office Architects (FOA), recognized as one of the world’s most creative design firms. Educated at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, University College London and Dundee University, Moussavi has taught in academic institutions worldwide. She was a member of the Steering Committee of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture between 2004 and 2015 and has been a trustee of the London Architecture Foundation and the Whitechapel Gallery in London since 2009. She was elected a Royal Academician in 2015 and has published three books.