[Goodsill House, photo by Victoria Sambunaris]

In the winter of 2017, BUILD met with architect Dean Sakamoto on Oahu to talk about the late Hawaiian modernist architect Vladimir Ossipoff (1907-1998). Sakamoto operates an architecture practice in Honolulu and guest curated the 2007–2008 exhibit Hawaiian Modern: The Architecture of Vladimir Ossipoff at the Honolulu Museum of Art. Sakamoto is widely recognized as the world’s leading expert on Ossipoff, known as the master of Hawaiian architecture within the postwar phenomenon of tropical modernism. We talked about the challenges of getting to know Ossipoff’s work, the architect’s life, and his design response to the Hawaiian environment. Part 2 of the interview can be read here.

What first sparked your interest in Vladimir Ossipoff’s work?

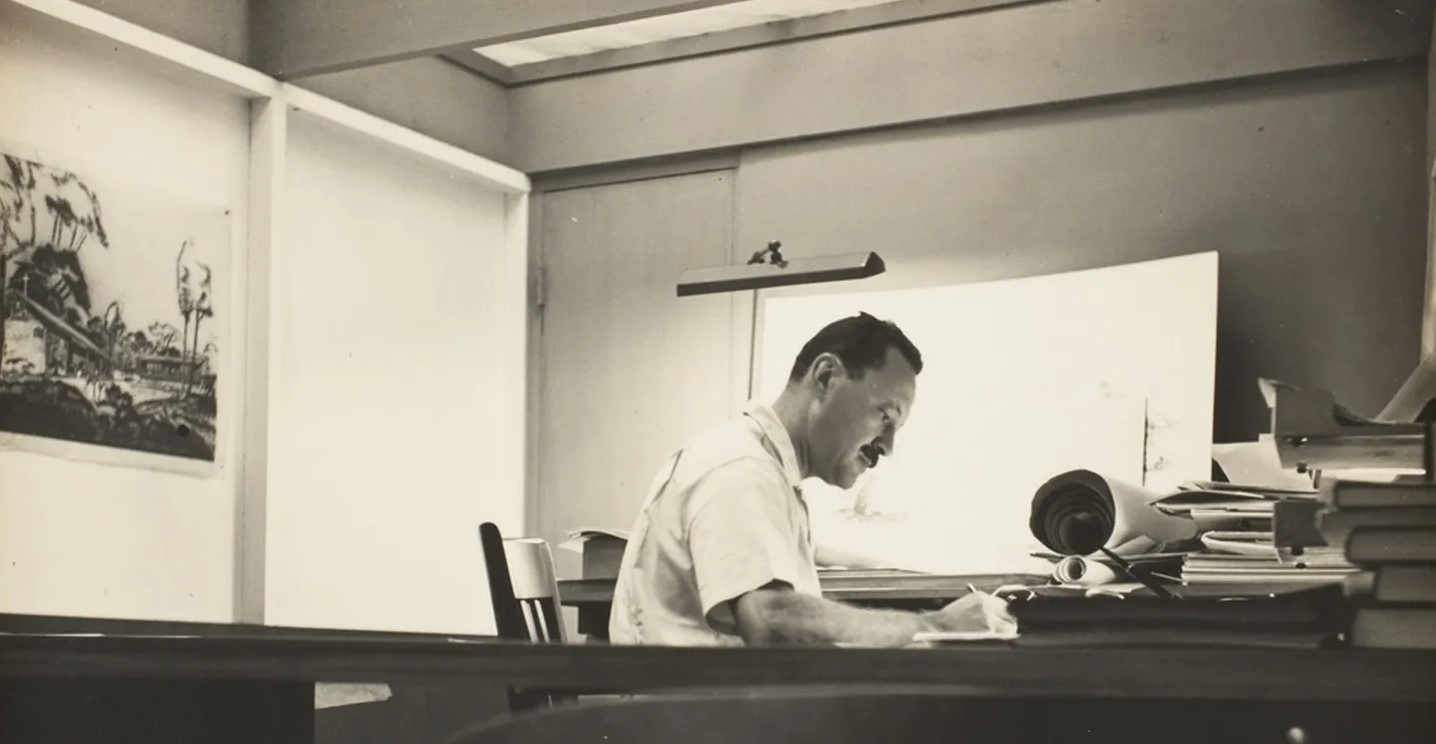

If you lived in Hawaii and were interested in architecture, you would hear his name, but if you didn’t know Ossipoff personally, he was a myth, a living legend. My work on Ossipoff started when I was on Yale’s faculty in the late ‘90s. I was designing houses in Hawaii from my New Haven office and looking for a precedent for good residential architecture in the area. Naturally, Ossipoff’s name came up, but since there were no books on his work, I had difficultly finding information on his projects. It wasn’t until I began researching older periodicals that the breadth of his portfolio became clear. He was all over magazines during the ’50s and ’60s.

The next time I visited Hawaii in 2001, I met with his business partner, Sidney Snyder Jr., who mentioned that since Ossipoff’s passing in 1998, people had been asking him how to best honor his life and work. At the time, I was the director of the architecture gallery at Yale, and Sid introduced me to the director of the Honolulu Museum of Art. I put together a proposal for an exhibit on Ossipoff. Until then, no one had formally researched his work, as tropical architecture had been marginal in academia when Ossipoff was completing many of his notable projects in the ‘50s and ‘60s.

Given Ossipoff’s background—born in Russia, raised in Japan, and educated at Berkeley—what were his primary influences?

Global events shaped his life and career. He was born in 1907 in Vladivostok, Russia, near Korea and Japan. After the Russo-Japanese War, the Japanese emperor invited Tsar Nicholas to open an embassy in Tokyo, and Ossipoff’s father, a Russian diplomat, was assigned to this assembly. This became Ossipoff’s ticket to Tokyo and Yokohama from 1909 up through his early teens. His family left after the Kanto earthquake in 1923, but because of the Bolshevik revolution in 1917, they couldn’t go back to Russia. Instead, they migrated to California. He saw Hawaii for the first time on a one-night stopover while traveling there by way of steam ship.

He finished high school in California, and in 1931 he graduated from UC Berkeley with his architecture degree, trained in the Beaux-Arts style. It was the Great Depression, and a friend wrote to him that there was work in Hawaii because the sugar industry was strong. He hopped on a ship and arrived in Honolulu that same year to build his life and career.

During his first six months in Hawaii, he was employed by local architect Charles Dickey, and he eventually found a job in the design and construction department of C. Brewer, a major sugar cane planation corporation. The architecture at the time was eclectic, and the predominant design approach was most similar to the Mediterranean style.

In Ossipoff’s own words, he came to Hawaii knowing nothing and learned from the Japanese-American draftsmen he worked with, who were very knowledgeable about how buildings go together. When Ossipoff opened his own office in 1936, he took one capable draftsman, Harry Onomoto (a second generation Japanese American), with him and continued to recruit talented architects with an eye for modernism.

At first, his work was more cottage-like. His understanding of the organization of a typical Japanese-style house was always present in his design sensibility though, and after some time, his work became radically modern.

[Liljestrand House, photo by Bob Liljestrand]

Despite weathering and the general wear and tear on the built environment, Ossipoff’s work is holding up well. What do you attribute this to?

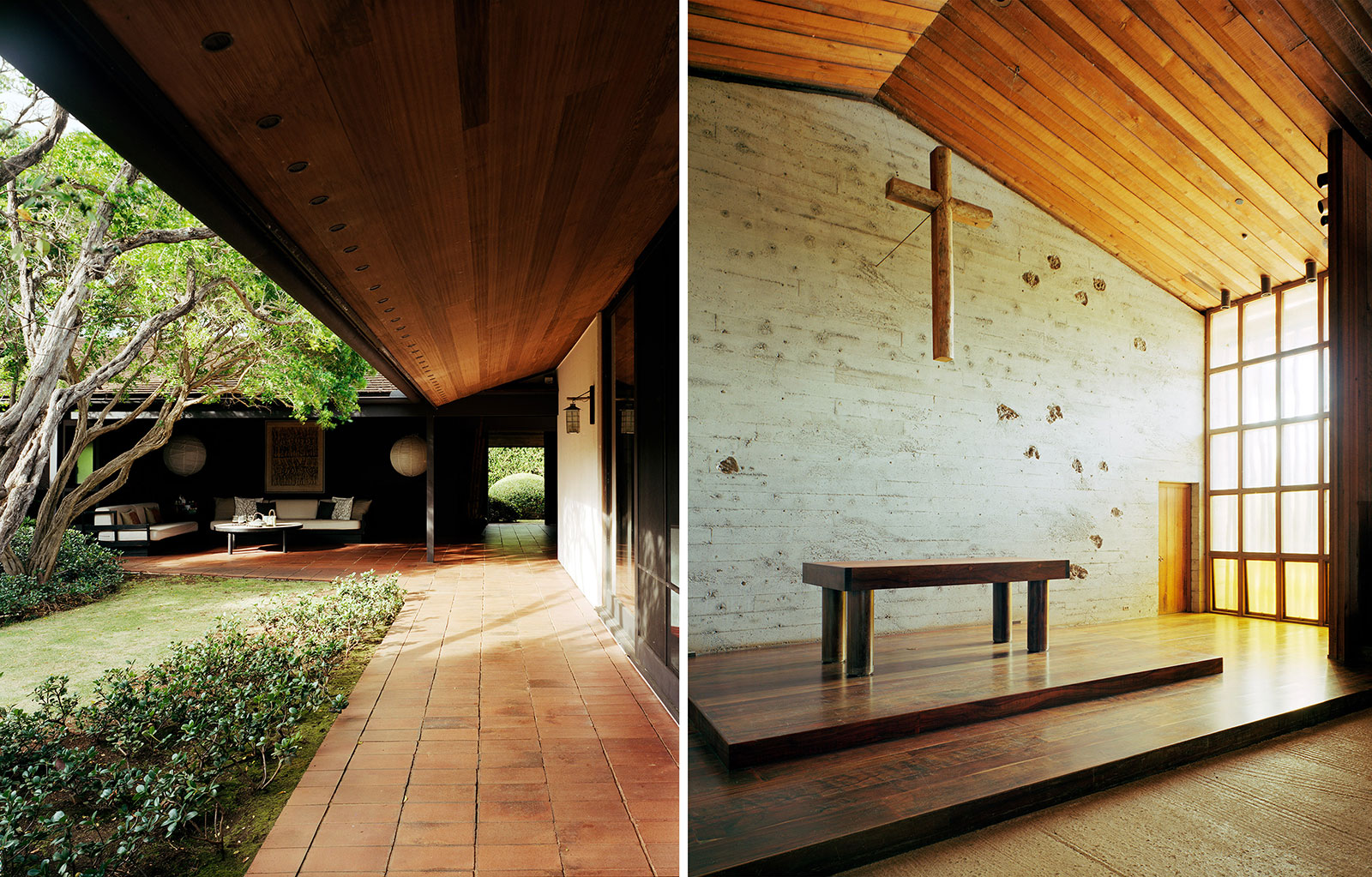

While Ossipoff was designing in the spirit of the international style, he also wanted to make it clear that his was a different kind of modernism. His was a regional architecture responsive to the particularities of the place. A good example is how in most of his projects he designed deep overhangs that protect his buildings from rain and strong sunlight. Ideas like this connect with the conditions of Hawaii and have upheld the aesthetics and function of his projects over time.

One of his greatest architectural achievements was bringing the indigenous lanai—an open-sided, post and beam, lightly roofed structure—from residential applications to larger-scale civic projects. How have these spaces performed over time?

Reinterpreting the lanai into modern design might be his greatest contribution to Hawaiian architecture. It blends in with nature rather than trying to dominate it. His most well-known lanai on Oahu is at Honolulu International Airport, which Ossipoff modernized in the ’70s. However, his best example is most likely at the Blanche-Hill house built in 1961, where the client told Ossipoff that she wanted a lanai to live in. The collection of lanais designed into the Outrigger Canoe Club is also a particularly good example. The Outrigger Club exists to perpetuate the Hawaiian water sports of paddling and surfing, and the lanais create excellent spaces for gathering.

Ossipoff understood the subtle considerations regarding the design of lanais. Because they are open to the weather, they inform the materials around them, such as the adjacent floors. The structures also continue to perform well as Ossipoff understood the trade winds and the daily weather patterns.

[Outrigger Canoe Club, photo by Walton Tregakis]

What did sustainable design look like in Ossipoff’s eyes?

He was very responsive not only to environmental issues but the politics of the time. In the ‘70s, when the oil crisis became a household concern, Ossipoff decried the presumptive use of air conditioners and designed natural ventilation into his projects where possible. He predicted an energy crisis and was adamant about looking at natural solutions before mechanical ones. This thinking informed his design philosophy.

Can you speak to the importance of darkness in Ossipoff’s work?

Ossipoff was a master of darkness and air. In the West, we always think about the quality of light, but in Japanese culture, darkness is equally important. It would seem that he was aware of the writing of Japanese author Junichiro Tanizaki, who published the novella In Praise of Shadows in 1933. Like Tanizaki, Ossipoff appreciated the natural material of something that could be better understood in the shadows, as opposed to putting lacquer over it and exposing it to direct sunlight. Its richness becomes visible in the shadows.

[Davies Chapel and Goodsill House, photos by Victoria Sambunaris]

Can you speak a bit about Ossipoff’s concern with large-scale development?

When Ossipoff arrived in 1931, there was very little development on Oahu. There were no real zoning codes there until 1967, and as development began, he and many other architects felt like they needed more control over the type and quality of work that was occurring. It was around 1964, when he was elected president of AIA Hawaii, that Ossipoff began what he termed his “war on ugliness.”

When Hawaii became a state in 1959, the first Boeing 707 full of tourists landed almost simultaneously. Up until that point during the Territorial era, Hawaii was an exclusive destination for wealthy people with the time to travel by ship, but with the jet age of tourism, Hawaii (Waikiki Beach in particular) became a budget vacation spot. At that time, anyone who owned a piece of land on Waikiki could put up a hotel, and many of the architects and developers on the island seized the opportunity to capitalize on the new demand for budget holiday accommodations.

The “war on ugliness” you mention indicates Ossipoff’s struggle to counter what he felt was poor design and the unrestricted development of Honolulu. How is the battle going?

Ossipoff would say that with regulation you still need design. Design requires taste and skill that not every architect has.

This is one of the reasons that I became interested in putting together the exhibit, book, and film on Ossipoff—he’s the protagonist of the Hawaiian Modern Project. Every time I would come back to Oahu after living abroad, it seemed so odd to me that we have such a beautiful natural environment here, but the built environment is such a contradiction.

What is the most important aspect of Ossipoff’s work that visitors to the island should take away?

Architecture is a product of its time, place, and culture. There is also a productive balance of push and pull between an architect and client. Architecture can complement its environment—it doesn’t have to be invisible or dominate.

Dean Sakamoto, FAIA, is principal of Dean Sakamoto Architects LLC and partner of the SHADE group, an alliance of professionals who share expertise and interest in the built environments of the tropical and subtropical regions of the world. He was guest curator of Hawaiian Modern: The Architecture of Vladimir Ossipoff and editor of the accompanying book of the same title (published by Yale University Press in association with the Honolulu Museum of Art).

Dean Sakamoto, FAIA, is principal of Dean Sakamoto Architects LLC and partner of the SHADE group, an alliance of professionals who share expertise and interest in the built environments of the tropical and subtropical regions of the world. He was guest curator of Hawaiian Modern: The Architecture of Vladimir Ossipoff and editor of the accompanying book of the same title (published by Yale University Press in association with the Honolulu Museum of Art).

This interview took place at Ossipoff’s outstanding Liljestrand house (b. 1952). BUILD would like to thank the Liljestrand Foundation’s Bob Liljestrand, the son of the original owners, for opening up the house for the interview and contributing to the discussion.