[Images by BUILD LLC]

In the world of urban planning and development, there’s been a tremendous amount of discussion about missing middle housing lately at the state, county, and city levels. The term is summarized nicely by Wikipedia:

“Missing middle housing refers to a lack of medium-density housing in the North American context. The term describes an urban planning phenomenon…due to zoning regulations favoring social and racial separation and car-dependent suburban sprawl.

Medium-density housing is characterized by a range of multi-family or clustered housing types that are still compatible in scale and heights with single-family or transitional neighborhoods. Multi-family housing facilitates walkable neighborhoods and affordable housing, and provides a response to changing demographics.”

Here in Washington State, House Bill 1110 — referred to as the Middle Housing Bill — addresses this lack of critical housing by requiring cities in Washington to allow middle housing throughout residential areas, and by limiting how cities can regulate it.

Seattle’s Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) has also specifically addressed middle housing in the recently published draft of the One Seattle Plan:

“Accompanying the Draft Plan is a report on zoning changes in Seattle’s neighborhoods to increase housing choices, particularly middle housing options like 3-plexes, 4-plexes, and other attached and detached housing types in all of our Neighborhood Residential areas.”

It’s hopeful to see governments and jurisdictions not only recognize the affordable housing crisis, but pass legislation to encourage and support this desperately needed housing type. With this new legal and policy wind at our backs, it’s now up to developers and architects to navigate the complicated zoning and building codes, and actually provide middle housing.

Over the last several years, the BUILD team has taken this issue head on, and we’ve been strategizing methods to efficiently design, permit, and construct projects that address this typology. With an array of middle housing projects now constructed, we’ve had the opportunity to take what we’ve learned, refine the methods, and apply ever more accurate strategies to a host of different sites and situations in the Pacific Northwest.

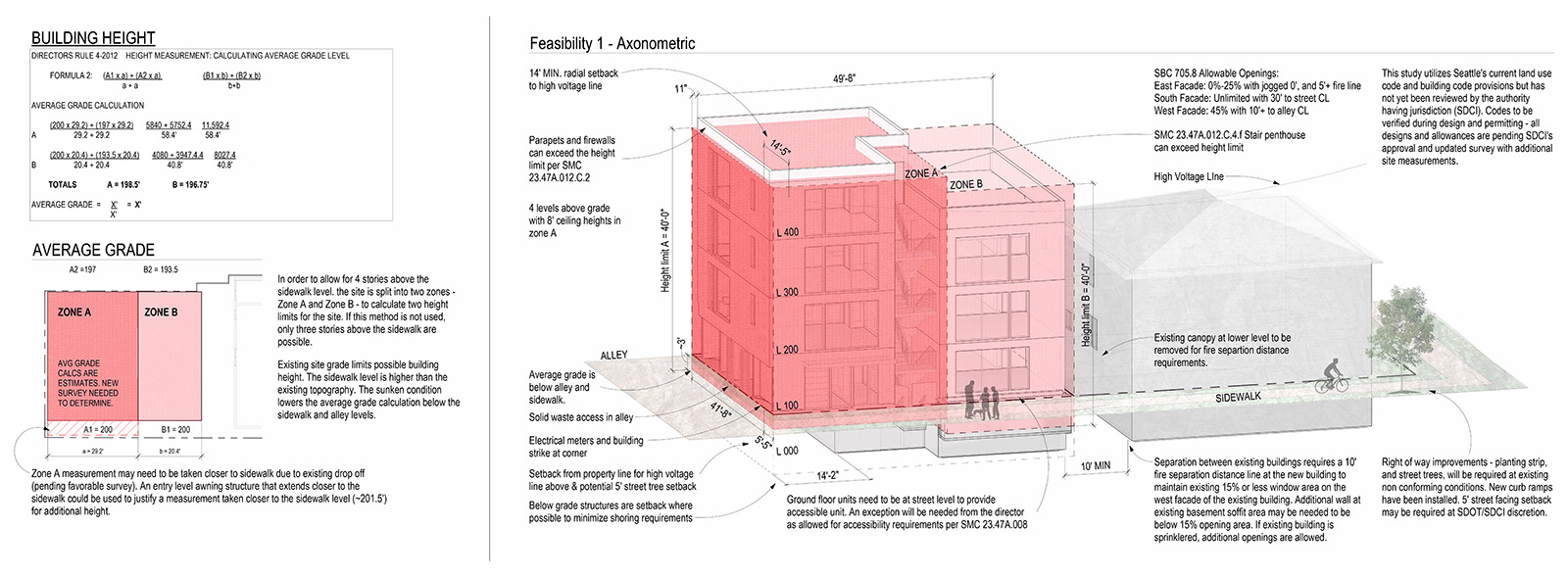

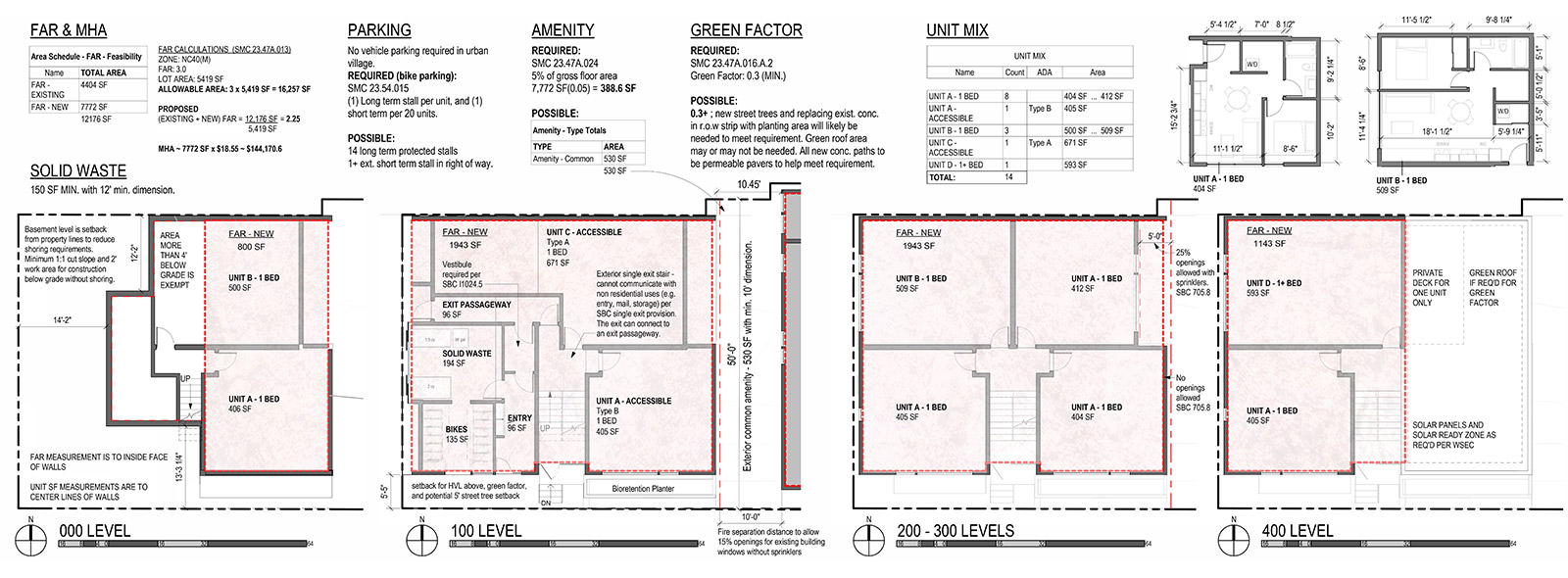

A recent feasibility study for a blank parcel of land in Seattle’s Fremont neighborhood demonstrates how well a particular set of strategies can turn a small urban lot into needed middle housing, and a financially sound long-term investment. Strategic planning, thoughtful design, and shrewd permitting allow a four-level, 14-unit apartment building on this tidy 5,400-square-foot parcel.

Of course, each building department has their own policies, each parcel has its own nuances, and each owner and developer have their own pro forma criteria. That said, we’ve found that the following five strategies apply to most jurisdictions, and establish effective development projects for the missing middle.

STAY ON TOP OF ZONING CHANGES

Each city has its own density allowances, and with pressure from the state, the zoning codes that regulate those density limits are prone to change—typically in service of greater density. If an architect is clever about it, every parcel in Seattle may now support a minimum of three units, and if the OPCD gets approval for the One Seattle Plan, this will increase to four units. Similar changes await a variety of different zones and density scenarios. If you’re a Seattleite, it’s worth staying in the loop via the OPCD website and social media platforms, and if you can tolerate the naysayers, the public meetings are announced here. The developers and architects who stay on top of zoning code changes will be aware of parcels whose value will increase significantly in the coming years; put differently, proposed zoning code maps help identify which parcels should be secured now to develop later.

MIND THE PERMITTING THRESHOLDS

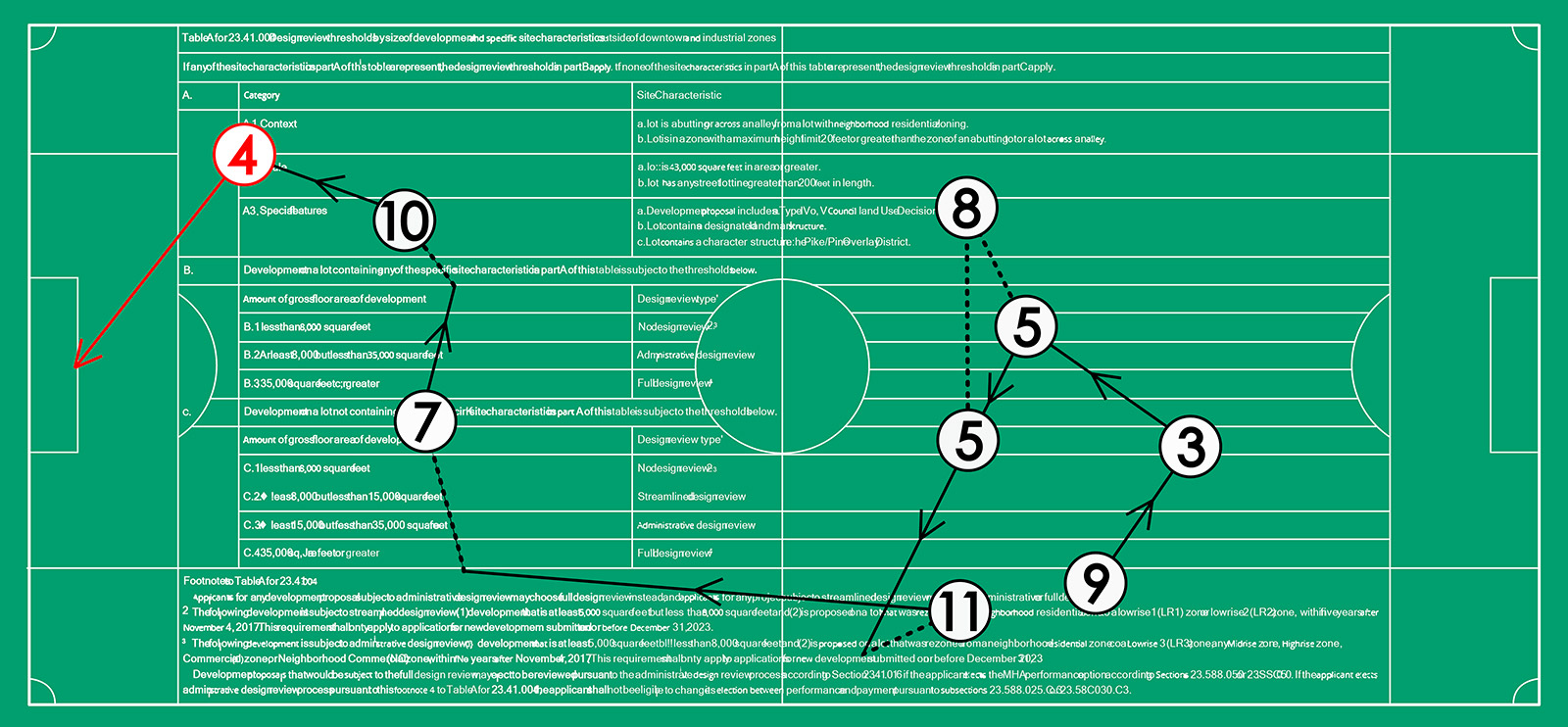

Many cities require a design review phase as part of the land use permit when a project crosses a certain threshold. These design review requirements are often time consuming and expensive; they also invite the City (or a committee) to the design table. While the intent of design review may have its merits, the bureaucracy it introduces to middle housing is a non-starter; the additional budget and red tape required of design review kills these projects on arrival.

Each city and jurisdiction has its own design review threshold. Here in Seattle, one of the more important ones is at 8,000-gross-square-feet for a multi-family project; above this a variety of different design review thresholds apply, but below this design review is not required. As noted above, in order to make middle housing pencil out financially, these projects typically need to be strategically designed under the 8,000-square-foot threshold.

THE DESIGN NEEDS THE NUMBERS AND THE NUMBERS NEED THE DESIGN

Middle housing needs to be designed from both ends at the same time. The project must hit certain metrics in order to support the pro forma, and the design needs to satisfy the building code, provide sensible dwelling units, and create a desirable building. Beginning design from only one of these perspectives jeopardizes the other; if the design isn’t using the correct numbers, the pro forma won’t work; and if the pro forma isn’t incorporating pleasing dwelling units, the project won’t rent.

One of the primary strategies from BUILD’s middle housing playbook is to minimize the circulation space in order to maximize the rentable area. With middle housing, we’re typically aiming for a rentable area between 85 to 92%. This validates the pro forma and keeps the project on a solid financial track. At the same time, key functions and amenities of a multi-family building need to be considered. Dwelling units should be light-filled and spacious, and their floor plans now need to incorporate space to work from home. These buildings require adequate utility rooms, practical waste and recycling facilities, and sensible bike storage. All of this needs to fit neatly within an inspiring and poetic architecture that stands out from all of the blandness on the rental market—because if the building isn’t occupied, it doesn’t really matter what’s in the pro forma.

BE WHERE THE BALL WILL BE, NOT WHERE THE BALL CURRENTLY IS

In pro sports, the true craft of a talented player is being where the ball will be rather than where it currently is. Development is similar in that developers and design teams need to be planning for where zoning, building codes, interest rates, and rental rates will be rather than where they are. These teams are working through the feasibility studies now so that when loan rates are more favorable, the property in question has already been vetted and the project has proof of concept. When developers who are late to the game compete with each other to get on the schedule of a knowledgeable architect, it is the savvy ones who have already secured optimal land and are in the permit queue.

GET YOUR ARCHITECT TEAM IN PLACE NOW

Lastly, and for all the reasons above, select your architect team early and establish cohesion with them; and institute a routine of performing feasibility studies on potential properties so the relationship is fluid and the architect knows exactly what to deliver and when. As soon as that gem of a parcel hits the market, these teams will have a seamless process in place to vet the property and forward the project before anyone else.

These five strategies, which are the result of 20+ years of designing, developing, and building multi-family projects, lead to a particular solution in and around the Pacific Northwest. The projects that best address missing middle housing are between four and twenty units, and typically no more than four stories. They conform to all of the strategies outlined above while fitting on the type of small, urban lots that are still available in cities like Seattle. Each region and city have their own criteria and design drivers, but given the nature of multi-family housing, we’re willing to bet that this project scale, along with these strategies, solve the missing middle in many urban areas.

For further tips, tricks, and guidance on developing the missing middle, we recommend this article on the Juniper Flats in Seattle.

Cheers from team BUILD