[Serpentine Pavilion, photo courtesy of Balmond Studio]

In the summer of 2018, BUILD met with engineer-architect-artist, Cecil Balmond at his London Studio to discuss his most recent projects and the thinking behind his experimental design process. Prior to opening Balmond Studio, his career spanned 40-plus years at Ove Arup & Partners where he worked on pioneering projects with renowned architects all over the globe. Balmond discussed the notion of architecture in a dynamic environment, the designer’s intuition, and his most recent projects. Part 2 of the interview can be read here.

In your lectures you’ve stated that the perfect modern box has been done and, at least in your own career, it’s time to move on. Can you expand on that?

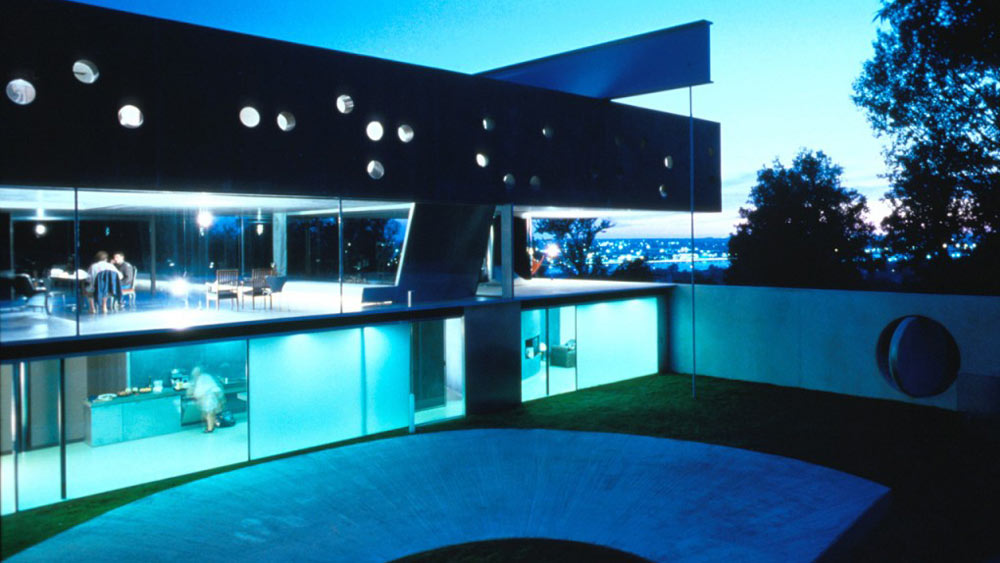

I don’t think it’s a question of modernism because the box has always been there. Designing with four corners and a closed, stable volume has been a way of thinking since classical architecture. And classical notions are fine if you want to repeat a box, but I think we need to deal with the box in new ways today. The simple solution is just cutting and distorting the box. Geometry is kinetic to me, it’s in motion, and it’s freeze-framed in architecture. With this method of thinking, I tend to take the edges of the box and extend them dynamically to create a vortex. The Bordeaux Villa that I worked on with Rem Koolhaas is a classic example of a box transformed, as is the Serpentine Pavilion in London that I designed in 2002 with Toyo Ito. They are both simple boxes, but you’d never think of them as such when you’re inside. These designs totally release the box.

[Bordeaux Villa, photo courtesy of Balmond Studio]

Describe the idea of architecture as a freeze-frame of kinetic geometry.

I always see design as a field condition. To me, the lines and vectors are always moving. In my book Informal, I wrote that I never see a column, instead I see a field condition of many columns from little stubs to giant trees, and I freeze-frame around that. Either this field condition is generated algorithmically, by instinct, or by specific design function. Whatever the generator, it’s part of a condition. The building never stops where I see it. If I have a building with six columns in it, there are 100 more outside that I am not seeing. It’s a field condition. So, the building is never a done deal in my design terms.

Do you believe there is a distinction between art, architecture, and engineering?

At its source, no. A good example of this is the Freedom Sculpture we recently designed for LA’s Santa Monica Boulevard. The piece honors Cyrus, the Emperor of Persia until 530 BC, for his advocacy of freedom, respect, and cultural diversity. The project brief was to lend inspiration to his first declaration of human rights 2,500 years ago. I had a simple concept in mind; I didn’t see an art object, I saw the spirit and the words travelling thousands of years, momentarily stopping in Los Angeles before the message of human rights carries on. This sequence of text takes the shape of a three-dimensional ring. If you look carefully at the form, nothing closes, and nothing repeats. The text is floating on a virtual surface of two cylinders. The effects of sunlight and shadow allow the text to be mobile.

[Freedom Sculpture, photo by Vafa Khatami]

You noted on the Portuguese National Pavilion that the concrete roof could have been thinner, but that a certain point is reached when judgement and intuition start to give warnings. How do you balance your intuition with your command of mathematics?

I always back intuition. There comes that moment in design, whether it’s a book or a building, where rationality produces logic, but intuition tells you not to trust the logic. It can be a very fine point, and if you don’t trust your intuition, you will not get a design that really sings. The designs I talk about that sing are a creative balance between the idea and the content. I’ve got a simple mantra that if it’s all about the idea, it stays ephemeral, it stays unreal in some way. If it’s all about the content, it accrues substance, it gets heavy. Only your instinct can allow you to find the balance between these two.

[Portuguese National Pavilion, photo courtesy of Balmond Studio]

It used to be that the structural engineer would guide the architect on what form could do. Then sometime in the mid-20th century, engineers became so skillful that the relationship flipped to the architect informing the engineer about how a building should perform to achieve the desired aesthetic. Did engineers outsmart themselves?

That’s a good question, an interesting question. In the early 20th century, you had architects like Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier coordinating with very capable technicians and technical draftsmen rather than engineers. In the ’40s and ’50s you get engineer-architects like Robert Le Ricolais in France, Frei Otto in Germany, Félix Candela in Mexico, and Eero Saarinen in the US, and each would have had a great sense of the structural capabilities of architecture. After this, I think the answer depends on the country. Ove Arup began Arup Associates in England in the 1960s, and the high-tech school began. London architects like Norman Foster, Richard Rogers, Renzo Piano, Michael Hopkins, and Nicholas Grimshaw all worked very closely with Arup, and there was a nice synergy between architects and engineers. In South America and Spain, architects continued to receive reasonable training in engineering, enough to design simple structures themselves. In France, where the word “engineer” contains the meaning ingenuity, an engineer is thought of as an ingenious person who creates the impossible. But in places like the Middle East, Asia, Russia, and the United States, the relationship became more of the architect simply telling the engineer “here’s the design, now do it.” Indeed, there was a flip in certain countries, and architects began to feel that the engineer was a technician without imagination. It may be that the advent of the computer allowed anything to be possible and freed the architect from asking “what’s possible?”

Is America still stuck in that trap?

America is for sure, I can tell you that. It’s only in England that there was a flowering, and Arup was the key. A few key people in Germany like Frei Otto and Werner Sobek also maintained architectural and engineering sensibilities.

Is there a point at which structural engineering becomes exterior decoration or even design fetish and, if so, do you guard against this?

I think that period is over. Structure became an end unto itself. Architects became so fascinated with the mechanics of structure that the architecture was stopped somewhere along the way. It was Le Corbusier’s creed that the building is a machine, comparing the building to a car engine or a plane, and the building’s functionality and efficiencies governed Corbu’s thinking. The high-tech school picked up on this, and there are buildings by great architects that turn me off because they’re all about structure rather than architecture. They’re showing off a kind of machismo about structural powers. That’s why I denounce the machismo of engineering in the introduction of my book, Informal.

You were instrumental to the design of the Seattle Public Library. Do you have a particularly favorite moment or design solution within the building?

There is a place within the Seattle Public Library where the diagonal steel lattice is required to span 60-feet at the public reading room. The typical depth of the steel lattice assembly wouldn’t work at this particular location because the span was too far, and this inclined plane would sag. To solve the problem, I piggybacked two of these steel lattice assemblies together, and it resulted in this beautiful effect. It was one of my happiest moments on the project, and Rem Koolhaas and I coined the phrase “stupid but smart” to describe it. It’s stupid because you’re simply putting the same thing on top of itself to solve the structural challenge, but it’s smart because of the effect. We use this concept as a kind of lever on our thinking.

[Photo by Andrew van Leeuwen]

Explain what you’ve done with the grid for the design of the National Taichung Theatre in Taiwan and how this changes the experience for visitors.

The National Taichung Theater uses what I call an emergent grid. But it’s a formal structure, it’s not algorithmically derived. The design alternates solid and void space like a three-dimensional chessboard. Then by stretching out the grid, you make bigger or smaller volumes, depending on the function. Bulbous volumes are formed, and the programmatic functions can be accommodated. This is more of a mobile or adaptive grid.

[Portuguese National Pavilion, photo courtesy of Balmond Studio]

Is there a project you’ve completed that would not be possible to design without the use of software?

Yes. We recently designed a project purely with numbers and fractals. The design process began with a solid cube, and we applied a logarithmic spiral in the shape of golden sections at different scales. This spiral of rectangles worms its way through the mass, excavating out the solid and leaving a void. We set the program loose in the studio, and we couldn’t believe how strong of a form it resulted in. There’s no way this could have been done without the use of a computer, and I’m dying to build this one.

Is there a particular book you consider required reading for architects and architecture students?

In this age of computing, I think there’s value in going back to some of the classical work like the books of Sigfried Giedion and Gottfried Semper. The classics are more difficult to read, but worth it if you stick with them. For newer work, I think Rem Koolhaas’s Delirious New York is an exciting read about typology. There’s also a little book by O. M. Ungers titled Morphologie: City Metaphors that juxtaposes city maps with images from science and nature which is quite fascinating. From time to time, I also read the last chapter of On Growth and Form by D’Arcy Thompson.

Cecil Balmond is a Sri-Lankan-British engineer, architect, artist, and writer. He received an MSc and a DIC from Imperial College, London, and a BSc from the University of Southampton. Balmond also studied at Trinity College, Kandy, and the University of Colombo. He joined Ove Arup & Partners in 1968, became deputy chairman, and founded the Advanced Geometry Unit (AGU) in 2000. In 2011 he founded Balmond Studio with offices in London and Colombo. He has taught at Harvard, Yale, the University of Pennsylvania, and the London School of Economics. He was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire in 2015 and was awarded the Thomas Jefferson Foundation Medal in Architecture in 2016.

Cecil Balmond is a Sri-Lankan-British engineer, architect, artist, and writer. He received an MSc and a DIC from Imperial College, London, and a BSc from the University of Southampton. Balmond also studied at Trinity College, Kandy, and the University of Colombo. He joined Ove Arup & Partners in 1968, became deputy chairman, and founded the Advanced Geometry Unit (AGU) in 2000. In 2011 he founded Balmond Studio with offices in London and Colombo. He has taught at Harvard, Yale, the University of Pennsylvania, and the London School of Economics. He was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire in 2015 and was awarded the Thomas Jefferson Foundation Medal in Architecture in 2016.