In a previous article we discussed the advantages of performing pre-design services during the land search and information gathering phases of a multi-family or mixed-use project. It’s highly advantageous to have an architect at the ready for this initial phase, and smart developers keep the design team on board for the next step as well. Once a parcel has been identified and an offer has been accepted, the property is no longer on the market and the feasibility period begins. This is mission critical time for developers and it’s when architects make some of their most significant contributions to a project. This feasibility period can last anywhere from one to three months depending on the agreement with the seller, and based on the constraints or challenges of the particular property. During this time, an architect’s efforts are focused on specific tasks that provide proof of concept to the developer, uncover enough concerns to walk away from the deal, or raise enough questions and concerns to negotiate more time with the seller. BUILD has been involved in all three scenarios, many times, as outlined in the five points below.

Feet on the Ground and Eyes on the Site

While a wealth of useful information is learned from a land use code study and property record search, nothing quite compares with the knowledge gained from a good old fashioned site walk. The trained eyes and lessons learned of a seasoned architect can tease out all sorts of characteristics: Does that standing water constitute a wetland? Does that pipe sticking out of the ground lead to an oil tank? Was the steep slope here all along or was it created by City roadwork? Could that tree be considered “significant”?. And so on. There are certain factors best discovered on site, and this information greatly supplements the data gathered from the research. Once the qualities of a property are known, the architectural team can get to work optimizing the benefits and turning deficits into value-adds.

Land Use Code Triage

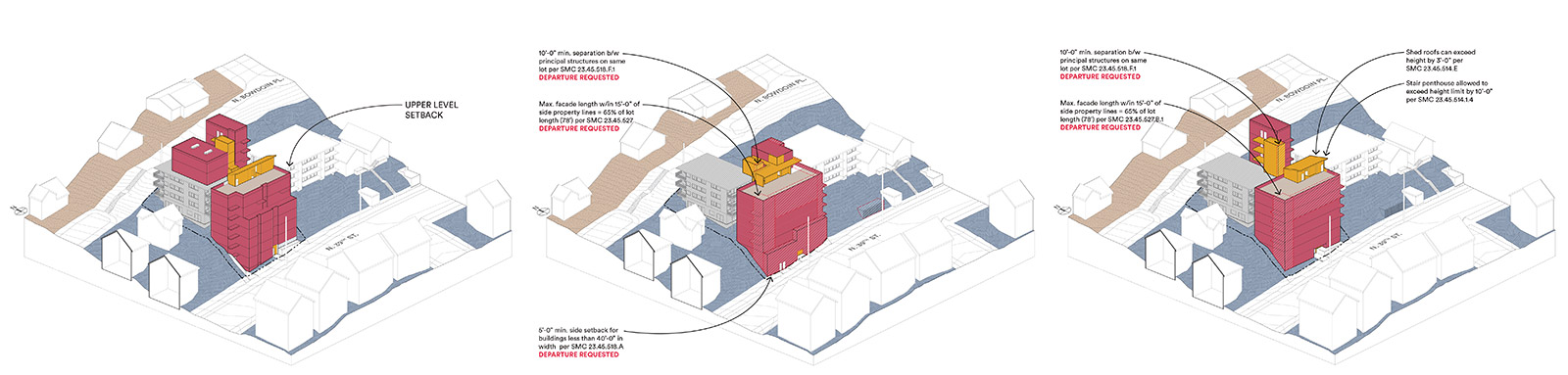

The current Seattle Building Code (2018 SBC) is a 35-chapter, 876 page tome and the Seattle Land Use Code (Title 23, Subtitle III of the Seattle Municipal Code) spans 45 chapters and includes hundreds of subchapters -to be sure, many cities have similarly thick codes. It would be easy for anyone other than an experienced architect to get bogged down by these codes for months. Navigating them requires not only experience in a particular jurisdiction, but excellent organizational and triage skills. The land use and building code studies decipher the relevant code provisions, and puts them into one of three categories:

- Critical to the intended development—these could be Environmental Critical Areas (ECAs), which directly limit the buildable area on a site.

- Possibly affects the intended development—these could be slide zones that need to be addressed, and are typically solved during the engineering of a project.

- Doesn’t matter to the intended development—this could be the thorny parking requirements outlined in SMC 23.54 for a site that doesn’t actually require parking due to its designation withinin a Frequent Transit Service Area.

With hundreds of code provisions affecting any particular property, this organizational system helps define the project well before the actual architectural design begins.

A Rapport with Consultants

Consultants, like surveyors, geotechnical engineers, civil engineers, and ecologists, are very busy these days so getting them involved early is key. Those who think that project consultants aren’t critical until the building design process has begun may come to rue such thinking. A 15-minute conversation with an experienced geotechnical engineer during the feasibility phase of a project can save weeks or even months of time. Checking in with the ecologist about what was learned on a nearby property can change the entire strategy of a project. Experienced architects have crafted relationships with reliable consultants for years and decades.

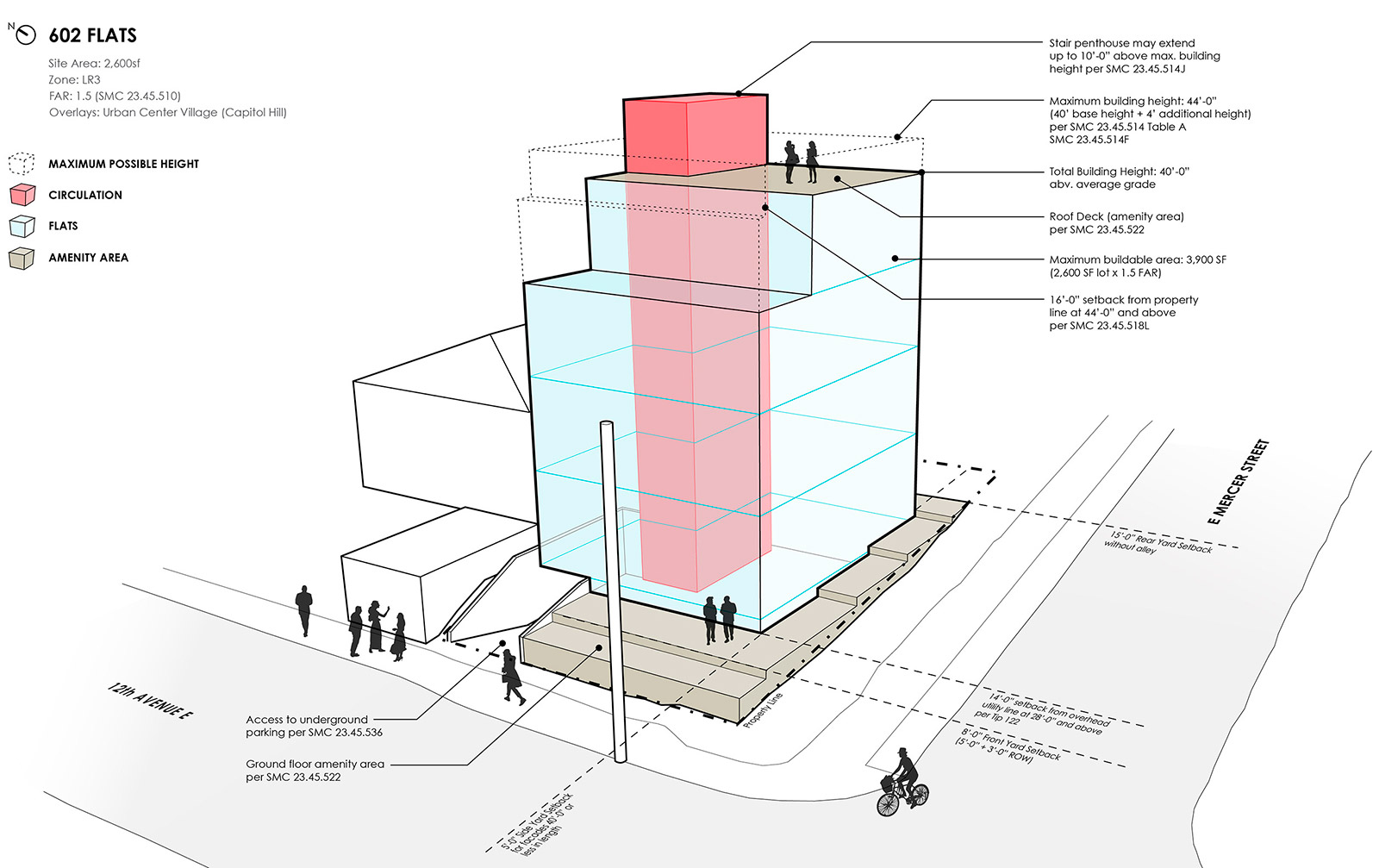

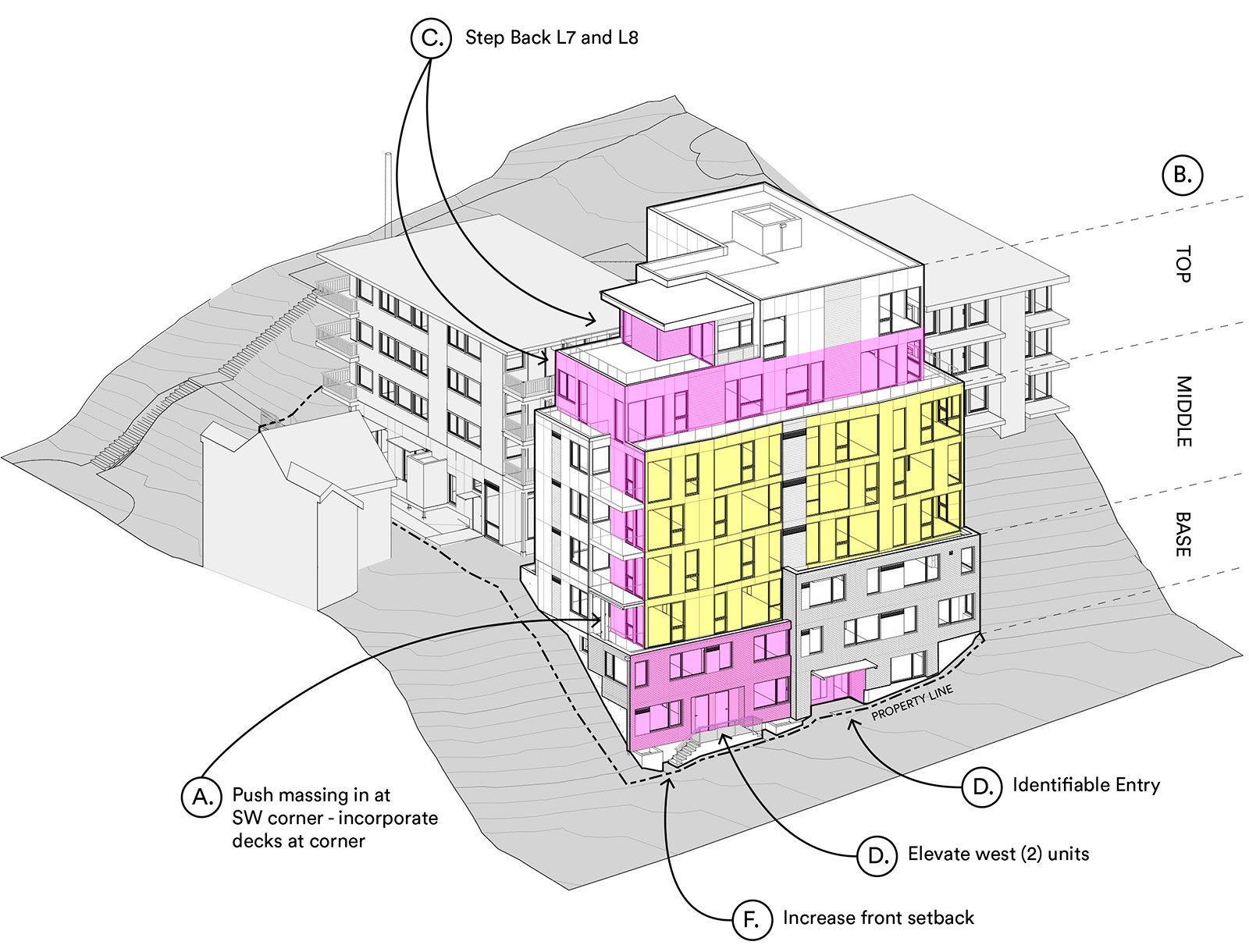

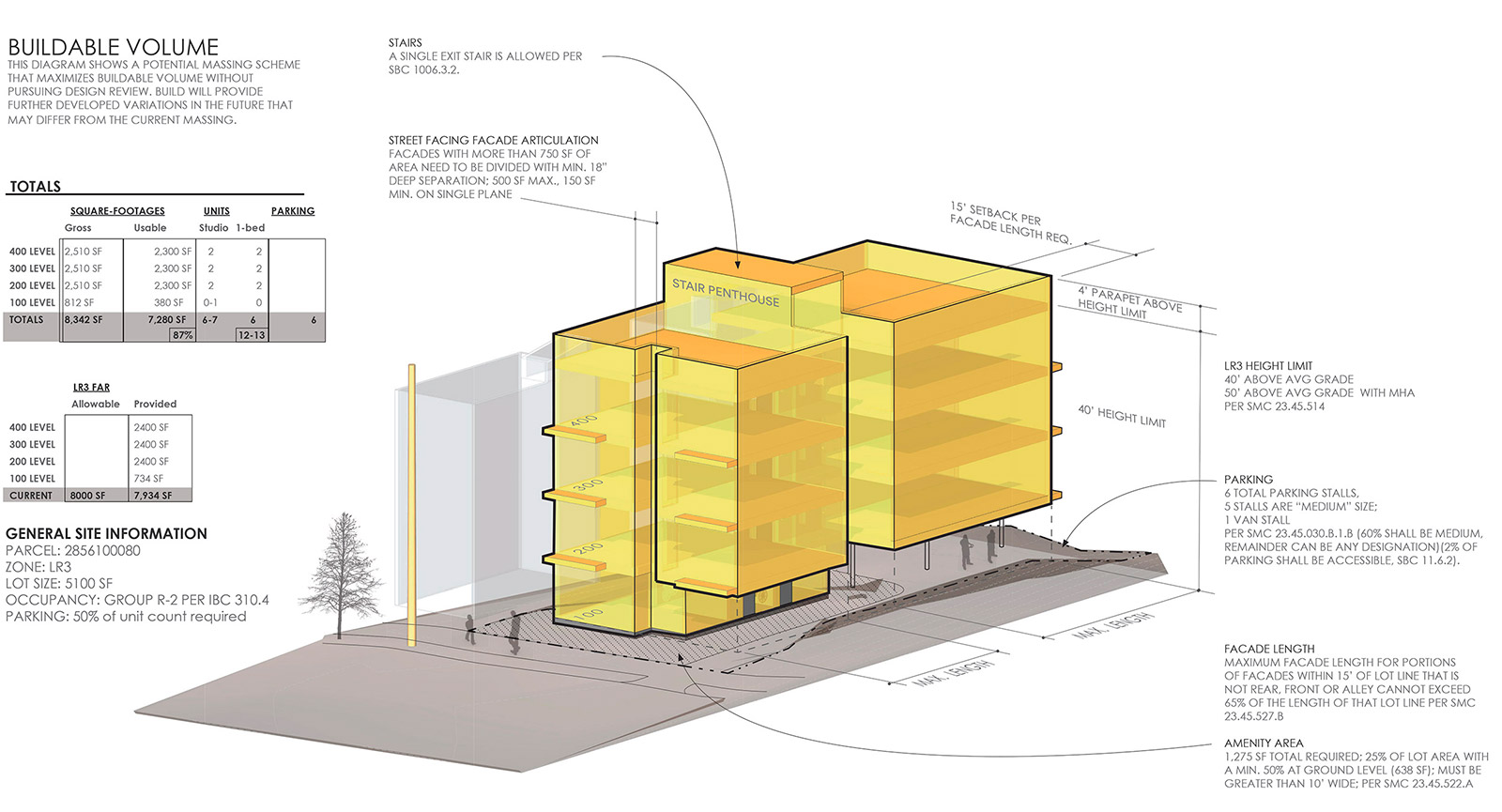

Multiple Schematic Models

The factors noted thus far provide enough datapoints for a design team to rough out two or three schematic massing models. This isn’t formal building design, yet, but it’s a graphic representation that considers all of the knowns and variables discovered up to this point. Models like this provide a sense of the optimal footprint on the site, and likely outline how many units will fit in the buildable volume. These broad-stroke models allow developers to sharpen proformas and aid in coordination with lenders. These simple site models also start to inform the design and development team of methods for turning site or code deficits into advantages: a sloped site can be optimized to maximize views and natural light; existing landscape features, like significant trees, can be planned around and celebrated. Features once thought of as limitations become value-adds to the project.

ROM Pricing

Architects who have been around the block a few times are knowledgeable about construction costs and know better than to sugarcoat the numbers. At this stage, even Rough Order of Magnitude costs are a tremendous benefit to the proforma.

In multi-family and mixed use work there are many indicators that a design team was brought on board early, including time savings, added value (profit), and well-earned sanity.

Cheers from Team BUILD