[Images by Åke E:son Lindman]

[Images by Åke E:son Lindman]

Back in the fall of 2015 BUILD visited Stockholm and met with Håkan Widjedal of Arkitekstudio Widjedal Racki. We discussed the influence of traditional Swedish design on modern architecture, the importance of understanding a client’s lifestyle, and how architecture can be a tool to interpret a site. Part 2 can be read here.

The important relationship between structure and environment is very apparent in your work. What have some of your greatest challenges been when navigating between design and context?

Nine out of ten clients who buy a piece of waterfront property to build on request that the broad side of the house faces the water, and they want windows that go from one end to the other to create a “wow” view. But this approach doesn’t address issues of privacy or climate exposure. If you really want to live with a property, the house needs to help out.

For the H-House located south of Stockholm, we designed a courtyard, which creates a microclimate. It blocks the wind from the southwest, and when it’s raining you can still sit outside under the covered area. There is also a fireplace for when it gets chilly in the evening. Since it’s entirely covered, the area can be treated more like a living room with nicer furniture, and it gets used more often because it’s semi-protected.

These kinds of design strategies allow the site to be experienced in a much richer way. The house becomes the right means to appreciate the place. The challenge is to address all of the environment’s qualities and lift them forward in a functional and emotional way. Our houses are less objects and more tools for using the site and enjoying the location.

How does your architecture respond to the long nights and overcast skies of Swedish winters?

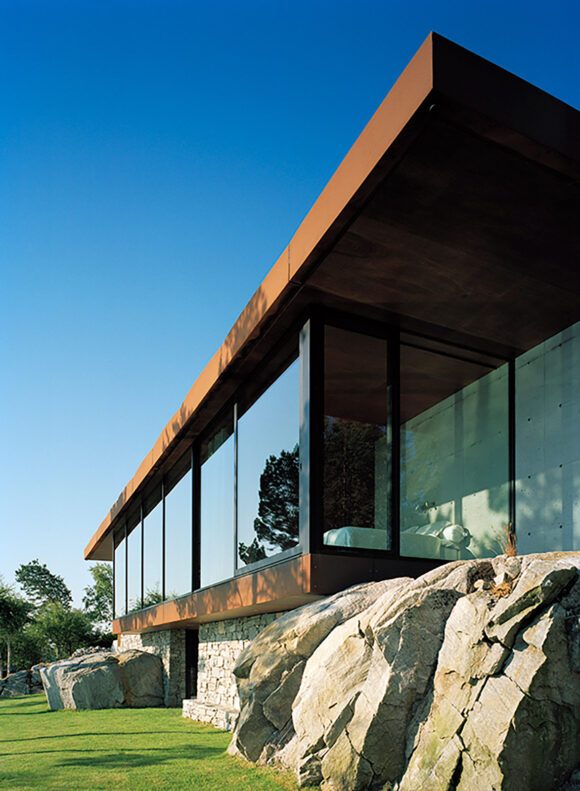

I think it’s tempting to approach these characteristics as negative features. However, in the Rock House, for example, we used a glossy ceiling to reflect light off the water, and it’s marvelous in the summer as well as the winter. When it’s cold, you can sit next to the concrete wall and the fireplace, both radiating heat, and watch the storms pass by. It’s a room that’s wonderful in good weather and bad. When you look at architectural renderings, the weather is always nice, the flags are always up and the kids are always playing. The challenge for architects is that this is not how the world works. Architecture has to work at all times of the year, and this depends on a few simple qualities. A house must communicate with the atmosphere of the site—it must be stable, secure and comforting.

Do you see common traits in your clients?

Our clients are genuinely interested in architecture. If you like nice things, you can simply buy a fancy sports car overnight, but you don’t go through the process of designing an ambitious house with an architect if you’re not interested in architecture. There’s a commitment to design there. Our clients also usually have nice properties in remote areas and quite often on the water.

Have your clients always lived the curated lifestyles suggested by the photos on your website or does the design enroll them in a clean and simple aesthetic?

We’ve designed a few projects that I certainly couldn’t live in myself, just because the minimalist kitchen wouldn’t tolerate a stack of dirty dishes—it’s not practical for most people. We have clients who will take your coffee cup when you’re done with it, clean it and put it back in the cabinet. Nothing is ever left on a countertop. They do this with everything without thinking, so a minimalist kitchen works for them.

What ruins architecture is when a design doesn’t work for a client’s lifestyle, requiring them to change how they live after the fact. We’re extremely keen on understanding our clients. It’s something we take very seriously. One of the things we’re most proud of is that none of our houses have been remodeled or altered. This means the designs have been right for the clients.

We’re very deliberate about designing for a rural lifestyle as well. A design might include an outdoor closet for wet or dirty clothes and shoes, or a tidy storage area to keep the firewood dry. There is always a thoughtful solution for where to put your stuff. It makes me a bit angry to see inspiring images of architecture, and then go visit it in person and find it doesn’t work. The photographs don’t always represent the truth.

We’re very deliberate about designing for a rural lifestyle as well. A design might include an outdoor closet for wet or dirty clothes and shoes, or a tidy storage area to keep the firewood dry. There is always a thoughtful solution for where to put your stuff. It makes me a bit angry to see inspiring images of architecture, and then go visit it in person and find it doesn’t work. The photographs don’t always represent the truth.

Do you think that the media has changed architecture?

I think a lot of the architecture that people are familiar with today is rarely experienced firsthand. Their understanding is limited to what they see in books, magazines and newspapers. Yet earlier architectures are so important because of the experiences those places provide. The paradigm shift that can occur when architecture is experienced in person can open up different possibilities for appreciating why the buildings are important; when you visit these buildings, you get a whole new level of experience. Today, the idea of architecture may have become more valued than the physical architecture itself. I think that media has turned the focus of architecture into something two-dimensional. The large supply of media has also pushed for making more “noise” in order to be seen. I sometimes feel that what could be called “headline architecture” gets too much notice. To me, architecture’s most significant role is still physical.

Given that you practice in a country with a rich architectural history, what effect has traditional Swedish architecture had on your work?

To be honest, when you’re fresh out of school, you have identity issues. You’re not going to be excited about what you grew up with. When I was younger I fled from Sweden’s local design thinking. I wanted to do what the rest of the world was doing. As I’ve become older though, I’ve actually become interested in looking at traditional Swedish design principles. There are always local factors that take design in certain directions, and more and more I’m influenced by the craftsmanship of the past. We’ve worked with massive timber construction, which is really an old way of building log houses, and the Villa Alba in Stockholm uses a wood corner detail that’s based on a traditional method. There’s so much information that you can get for free—architecture that’s right in front of your eyes that you can build from.

One of my favorite architects is the late Ralph Erskine, who was actually born in England and then moved to Sweden to work. Because he was really looking at the local qualities and environmental issues objectively, his work is some of the most Swedish in my opinion. At the same time that he was designing, Swedish architects were blind to their environments because they wanted to practice international principles. Because he wasn’t from Sweden, he could create architecture that was more authentically Swedish. As the saying goes, you never become a prophet in your own village.

There is a pleasant intersection between the roughness of nature and the refinements of architecture in your work. How much of this is situational and how much is planned?

It’s very much planned. If we were designing a penthouse in Stockholm, it might not include much roughness at all. But with our rural projects, the roughness is quite practical. For instance, the rough concrete floors in many of our projects allow people to wear their shoes inside. If we had put expensive wooden floors in some of our rural houses, clients would be constantly concerned about damaging them; that would not embrace the idea of relaxing and enjoying the site. In the bedrooms, we lift the floor up to separate them from the concrete so that there is a warmer and cozier feeling where it’s appropriate.

How is the weathering of material planned for in your work?

How is the weathering of material planned for in your work?

We plan quite a bit for weathering. Most of our clients make it very clear that they don’t want to spend their summers repainting windows. While there’s no such thing as a house that doesn’t require maintenance, we always focus on limiting the work required to keep up one of our projects. Once again, there is a tremendous amount to learn from traditional architecture here. There are wood churches from the 1200s that are standing perfectly fine because they are detailed and treated the correct way.

Concrete cracks and wood expands. How do you set reasonable expectations with clients regarding the fact that there’s no such thing as truly perfect?

It’s about seeing the roughness as a quality. It’s a mindset. It’s good that it’s rough, and once you have that outlook, the design can be more fully appreciated. Practically, setting expectations is also about visiting other residences and showing clients how we’d like to do something. A lot of the natural materials we use age beautifully. Choosing materials that will age nicely matters; it’s hard to make a laminated desktop age well.

Is there anything else you’d like to talk about?

Although I don’t like labels, a lot of people refer to our architecture as very modernistic. To their credit, we have been very influenced by the classic modernists, such as the architects involved in the Case Study House program. But it’s important to point out that even the Case Study Houses were heavily focused on their environments. In the same way we work, the Case Study Houses were designed as methods to optimize their environments. This approach is less focused on style or expression and more about architecture as a tool. Buildings are not supposed to be symbols representing something. They’re supposed to create atmospheres.

Håkan Widjedal started Arkitektstudio Widjedal Racki with Natasha Racki in 2000. The firm specializes in private residences and has taken part in several exhibitions. His work has received numerous awards, including the Swedish Wood Award. Håkan has taught at the Architecture Faculty of the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm and has lectured widely.

Håkan Widjedal started Arkitektstudio Widjedal Racki with Natasha Racki in 2000. The firm specializes in private residences and has taken part in several exhibitions. His work has received numerous awards, including the Swedish Wood Award. Håkan has taught at the Architecture Faculty of the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm and has lectured widely.