[Images courtesy of Smith-Miller + Hawkinson]

In early autumn 2013, BUILD sat down with architect and Columbia professor Laurie Hawkinson in the Manhattan offices of Smith-Miller + Hawkinson (SMH+U), which she runs with her husband, Henry Smith-Miller. They discussed SMH+U’s advancement into public projects, working with different types of clients and the education of an architect. We hope you enjoy this interview from our archives.

SMH+U’s work spans everything from furniture and houses, to museums and transportation terminals. Do you consider yourselves specialists at any particular project types?

We started out doing a lot of residential work. Since you begin with the project types that are coming in the door, we first developed a vocabulary of details for lofts. However, I was very interested in working in the public realm, and at a certain point we decided that was what we really wanted to do. Of course, you can decide that, but then you actually need to do it. This was at a time when public work was available, so we started putting feelers out. As we took on more public work, we deliberately took on less residential work. Our public projects — such as the EMS station in the Bronx, which is currently in construction — have been some of the most interesting to us. We’ve also completed a couple of GSA (General Services Administration) port of entry projects, and we remain interested in that infrastructure.

How long did it take to get into public work?

Serendipitously, one thing has always led to another. Early on, we were approached by a firm that was working for Continental Airlines. They came to us because we had done all of these interior projects, and they wanted us to help design the interior package in conjunction with the new branding they were rolling out for Continental. Carpet and surfaces turned into new ticket counters for a terminal at La Guardia, which turned into a canopy to shade the sun—the project ultimately became a design strategy for the whole environment.

After that we submitted an RFP for the ferry terminal here in New York City, and because of the Continental project, we were seen as transportation experts. We got the job, which was an important turning point in our portfolio of public work. Shortly thereafter, Corning Glass approached us because of our innovative use of glass and Kevlar on the canopy design for Continental. They were interested in having us design an exhibit, which established a good relationship between us, and when the Corning Museum of Glass came along, they gave us the project. We had never done anything of that scale, and the project was a significant milestone for us. It’s about getting a foot in the door and not letting it close.

Your website states that your work derives inspiration from an “ongoing investigation into contemporary culture, its history and its complex, changing relationship to society and contemporary ideas.” What aspects of culture are you currently interested in?

I’m interested in the next five minutes—I’m interested in what I don’t know. I like to think of it as someone giving us a script. As architects, we apply our design lens to this script and give it back in some other form. That cultural lens focuses on how to make a particular program relevant today in terms of the way we live. The criteria are always changing based on the situation and the program, but the lens is consistent.

With investigation and speculation playing an important role in your firm’s design process, is there a threshold in which the office becomes too much a laboratory and you feel the pressure to produce?

That threshold is probably our bank balance. As an architecture firm, you gain edges in certain areas, which provides the financial breathing room that supports creative exploration. Having bought our office in Manhattan a long time ago, our overhead is very low, and it’s become an advantage that allows us more freedom to investigate, speculate and make those extra models if we want.

SMH+U recently completed the Dillon condominium building in Manhattan. How was your experience working with a developer?

Henry and I heard Max Abramovitz speak at the Architectural League years ago; he warned architects to “never work for developers,” but that was a different time. Not long ago there was a shift, and developers in New York are now realizing that they need architects to really sell the product. They see value in design. While many developers have been bitten by the design bug, it’s important for architects to remember that development work is still about the bottom line.

The resurgence of housing construction in New York is apparent in most neighborhoods. Would you consider it good growth?

Luxury condos are being built everywhere in Manhattan, which is very different from housing. In neighborhoods like SOHO, it’s second and third homes for owners who don’t live in New York. We need more density in Manhattan, more actual housing. New York has made some good decisions with the 2030 zoning changes under the direction of the Mayor and Amanda Burden, but now we need the policy to back it up.

In 1993, SMH+U designed a weekend house for Kenneth Frampton, maybe the most knowledgeable architectural historian alive. How did the design process differ from other projects?

He was actually trained as an architect and then became a historian, and his wife is also an artist. Given their backgrounds, the design process was a collaborative conversation in which the clients were very knowledgeable about architecture. It was a challenging project because of a strict budget, a minimum required footprint on the property, and because none of the local builders had ever built anything like it. Because of the constraints, part of the conversation was that in terms of the design we got one big move, which became lifting the house up.

Having studied under John Hejduk and Bernard Tschumi at The Cooper Union, what lessons of theirs have been most influential to your career?

There was an unspoken standard at The Cooper Union that we simply felt compelled to uphold, from the thinking down to the quality of the models and drawings we produced. Hejduk was involved in everything; he was involved with the thesis program and was very hands-on. He was also very suspicious of perspective, so we drew in axonometric and worked a lot in model, which has guided the way that I think. The things that we produced weren’t necessarily precious, but they were important to iterate and learn from.

There was a heightened sense of learning how to think based on what we made—the connection between brain and hand. This relationship is very ingrained at Cooper Union. There was attention to the way things are put together. The program of a project became very important — it was an interpretive device. You had to take apart the idea of a house before you could design one. It relates back to the idea of being given a script and then applying your lens to it.

Bernard is very conceptual, and he doesn’t sketch like most architects do with literal drawings or diagrams; instead, he notates. He would use a system of notation to delineate the program and his sketchbook looked like battle maps or football formations. He wants to take you out of your comfort zone. This relates to deciphering culture.

In your experience, what are the most significant skillsets enabling students to excel in the architecture profession?

They have to think about what they’re doing. They have to be able to defend it with evidence, and the evidence is the work. They can break the rules, but they have to build a case. At Columbia, I think we’re training people to be leaders. They have to be able to go out into the world and know what questions should be asked.

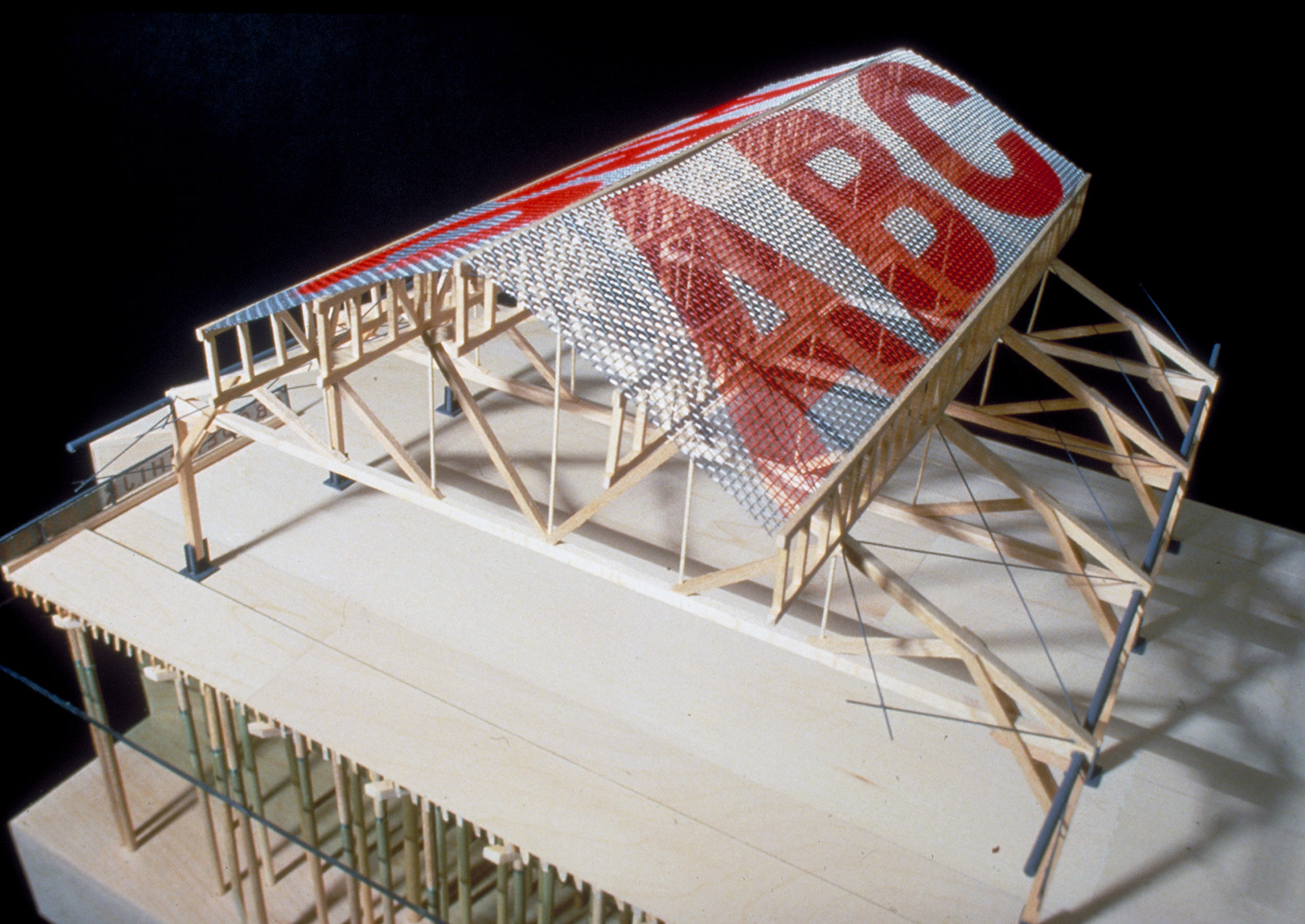

Tell us about the Seattle Waterfront Open Space Park project that you designed in 1989.

It was an Art and Public Places competition with the site located at Piers 62/63, right next to the Seattle Aquarium. There was this incredible, old pier-shed on the site, and although it was a wreck, we felt it was very important to keep. We put together a study on the history of the pier shed and made the case to save it. Working with our super-engineer, Guy Nordenson, we decided to remove the envelope, but keep the structural timbers, and install a new envelope so that the building could become a pavilion.

We presented our design to the City of Seattle and later, on a weekend in the middle of the night, we got a call from the director of Public Places who told us that the building had been bulldozed. Someone was worried that a proposal that saved the building might establish a constituency for the preservation of the old structure. With the building gone, there wasn’t much to do at that point. Left only with the perimeter fence, the project became an exercise in words painted on the mesh of the fencing.

What is the best mistake you ever made in architecture?

Probably deciding to go to architecture school in the first place. I studied art at UC Berkeley, and I was doing installations that were site-specific. I came out to New York with the Whitney Program and then went to work at the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies where we did a show on Hejduk. When I met John Hejduk, I decided that I needed to learn more about architecture for the art that I was doing. A good friend of mine said, “You know, once you go to architecture school, you’re going to see the world differently, and you’re going to become an architect.” Architecture wasn’t something I intended to do. My friend was right—architects do see the world differently.

What’s on your nightstand? What are you currently reading?

The Great American University by Jonathan Cole—I’m also making my seminar students read it.

Laurie Hawkinson received a Bachelor of Fine Arts and a Master of Fine Arts from the University of California at Berkeley, attended The Whitney Museum of American Art Independent Study Program and received a Bachelor of Architecture from The Cooper Union. She has been the director of the Exhibitions Program for the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, and has been a principal at Smith-Miller + Hawkinson (SMH + U) since 1982. She is currently a tenured professor of architecture at Columbia University.

Laurie Hawkinson received a Bachelor of Fine Arts and a Master of Fine Arts from the University of California at Berkeley, attended The Whitney Museum of American Art Independent Study Program and received a Bachelor of Architecture from The Cooper Union. She has been the director of the Exhibitions Program for the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, and has been a principal at Smith-Miller + Hawkinson (SMH + U) since 1982. She is currently a tenured professor of architecture at Columbia University.