[National Assembly Building in Dhaka, photo via Wikimedia]

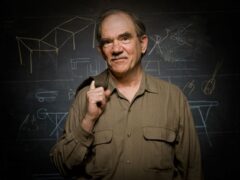

Last winter we visited Richard Garfield at his home in Portland, Oregon to discuss his work with Louis Kahn, teaching at the University of Oregon, and his current work with Rhiza Architecture + Design.

As the great grandson of our 20th President James Garfield, is there much politician in you?

No. My political leanings are kind of odd. I’ve always been a registered republican, and my wife is a democrat. My father was also a republican, and my mother was part of the academic community in Cambridge (and her dad taught at MIT and was a liberal), which meant that we had regular politically-minded visitors at our home. As such, there were always ongoing discussions in our house about political events.

How did you end up working for Louis Kahn?

In 1966, when I was in graduate school, a classmate of mine, Thom Hacker, invited me to a charrette at the office he was then working at, which ended up being Kahn’s office. I went and worked on a couple of chipboard models. Then, when I graduated in 1967, I went back to Kahn’s office and asked if he had a job for me, which he did. While I was there the office had a staff of 20 to 30, but it later grew to around 40 people, which was too big—the sweet spot was around 20. The office was spread over two floors at 1501 Walnut Street in Philadelphia; the fourth floor was production, and the fifth was design, which is where I sat for the first two years.

You were the construction administrator for Kahn’s National Assembly Building in Dhaka; how did that come about?

When the National Assembly Building came into the office, I was leading two small jobs and working on six others—everyone was putting in 70-hour weeks fairly consistently. So when Lou asked me if I’d consider going to Dhaka, I asked him in turn: Is it just one job?

[National Assembly Building in Dhaka, photo by Jatiyo Sangshad Bhaban]

One of my pre-Dhaka responsibilities was as field representative for the Olivetti-Underwood Factory building, which allowed me to meet the likes of Alberto Olivetti, who hired Lou to do their 350,000-sf building—which was only half the size of what they planned. The site, outside of Harrisburg, was among the richest farmland in the world. I worked on the design, which was spearheaded by Jack McAllister, who had served as the prime architect on the Salk Institute. I worked with him for a couple of months before Lou asked me if I’d do the construction oversight in Bangladesh. I worked on the Assembly Building for 11 months from a makeshift office, which was a former farm building on the site. I also worked on the second capitol with the army corps of engineers, but when the India-Pakistan war broke out, the project shut down because the corps was summoned to West Pakistan. It was a very difficult time.

What are the most important lessons you learned from Kahn?

He was very good with people; he could really read them and knew how to draw out their best. He also knew how to make difficult decisions quickly. For example, the Olivetti building had concrete block walls comprised of 28’-high panels of block and pre-cast concrete pieces; the concrete block had to be painted and sealed, and we had to choose a color. Lou was traveling a lot, so I drove to the airport to meet him between flights; I showed him some paint chips and asked him to choose one — for this extensive and important application! — and he did in very short order. He could be very quickly decisive under pressure—and he made excellent choices. I carry these examples with me to this day.

[Olivetti Underwood Factory, photo via archeyes]

I recently visited the Salk Institute where the signature courtyard is now gated off and security guards circulate around the building, keeping curious architects like me off the grounds.

Well, I can kind of understand, as the courtyard is the front yard of a workplace.

[Salk Institute, photo by Andrew van Leeuwen]

Do you believe it’s possible to do work at the level of Kahn’s projects in today’s political, social, and financial environment?

Yes. Renzo Piano’s work at the Gardner Museum is a prime example.

[Gardner Museum, photo via RPBW]

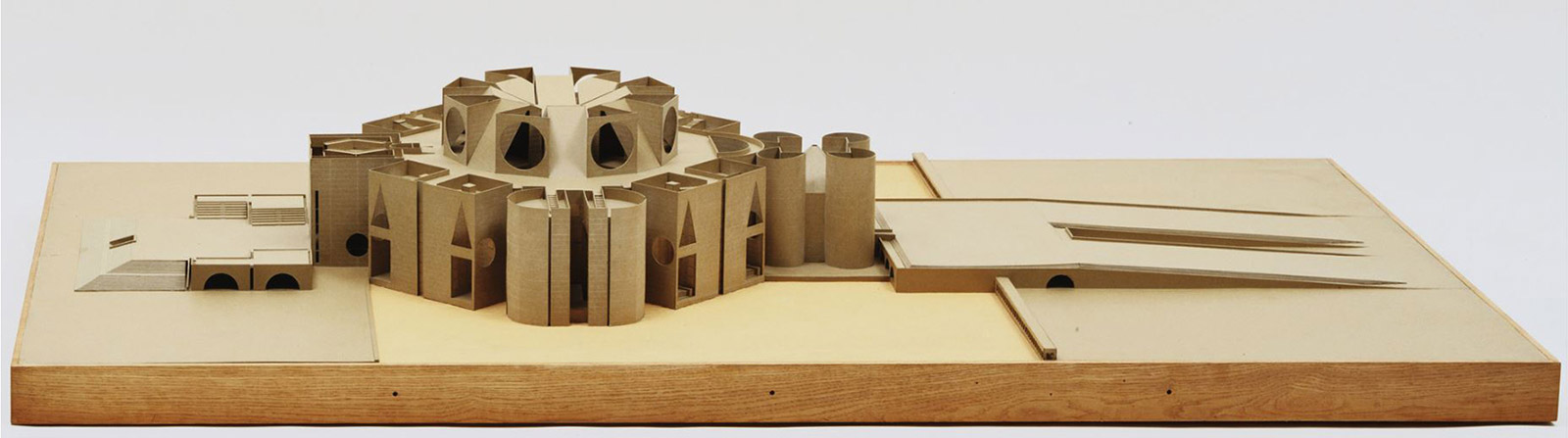

It’s said that Kahn would have the office build models of what his projects would look like as ancient ruins – is this true?

In a way. That’s how Lou designed—from the ground up.

[National Assembly Building model via MOMA]

Anyone who has watched the documentary My Architect is likely wondering how Louis Kahn kept three separate families secret from one another while running an architecture practice. How did he do this?

He was really charged up about hitting his stride in his 50s—he knew he had been given a special opportunity. He had a light in him, and a bee in his bonnet about getting stuff done.

What was your involvement on Boston’s City Hall with Kallmann, McKinnell & Knowles?

I worked on it for seven weeks.

[Boston City Hall, photo via Wikimedia]

You’ve worked on your share of what some might call Brutalist architecture—do you agree with the term?

No…maybe Boston City Hall would fall in that category, but I wouldn’t characterize Kahn’s work in this way.

Did your time teaching at the University of Oregon overlap with Christopher Alexander’s master planning? If so, what is your opinion of the design strategies?

He was just getting his claws into that place when I was there and we really didn’t interact. Shortly after I arrived I saw a student walking by with a huge book and I asked him if it was one of the code books that were ubiquitous at the time; he said “No, it’s A Pattern Language!” I really wasn’t aware of Alexander’s strategies on the campus.

What was your priority as an architecture professor?

I’m not an academic, but I am very interested in design and materials, so these subjects were paramount in my approach.

What do you believe is most important to impart to students in our current culture?

That they must work to find the spirit of any given project—of course they must also understand the nuts and bolts, but without a conception of the soul, the resulting work will suffer.

[Soundshell Internatural Station, photo by Rhiza R+D]

Where does the artistic side of your current work at Rhiza come from?

I’ve been working with a trio of guys for 25 years who each went to Cooper Union. They’re all trained as architects, but in addition, Peter Nylen is an excellent carpenter, cabinet maker and craftsman; John Kashiwabara is a wonderful writer; and Ean Eldred worked with his internationally acclaimed sculptor father, Dale, and brings that creative influence to the group. Since we started working together in the 1990s, in addition to architecture, we’ve worked on a number of art-minded projects, including theater, dance, and public art. For us, bringing together unique and diverse perspectives is the root of creating durable, long lasting and adaptable design solutions.

What is the most important books for an architect to have on their shelves?

On Growth and Form by D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson

Richard Garfield has practiced architecture 50 years: working for Louis I. Kahn; In Dhaka, Bangla Desh and in Kathmandu, Nepal, representing Kahn and working for the Ford Foundation, the U.S. Government, and the Kingdom of Nepal. In Oregon, he taught architecture at the University of Oregon, was director of architecture for DMJM / Hilton and president of Garfield-Hacker Architects, building at OHSU, Tektronix, Intel and museum sites in Oregon, Montana, Arizona and California. He is currently a partner with Rhiza Architecture + Design in Portland.

Richard Garfield has practiced architecture 50 years: working for Louis I. Kahn; In Dhaka, Bangla Desh and in Kathmandu, Nepal, representing Kahn and working for the Ford Foundation, the U.S. Government, and the Kingdom of Nepal. In Oregon, he taught architecture at the University of Oregon, was director of architecture for DMJM / Hilton and president of Garfield-Hacker Architects, building at OHSU, Tektronix, Intel and museum sites in Oregon, Montana, Arizona and California. He is currently a partner with Rhiza Architecture + Design in Portland.