We recently returned from New York City, and as it was our first time traveling since the beginning of the pandemic, we were more than a bit apprehensive to experience covid-stricken Manhattan. Although the city is a favorite design and cultural destination of ours (as it is for so many), this time around our usual enthusiasm was mixed with a considerable dose of apprehension. There’s no lack of media coverage on the civil, social, and cultural damage caused by Covid, so our radar was on high alert for indicators of its negative impacts on the urban environment we love and know so well.

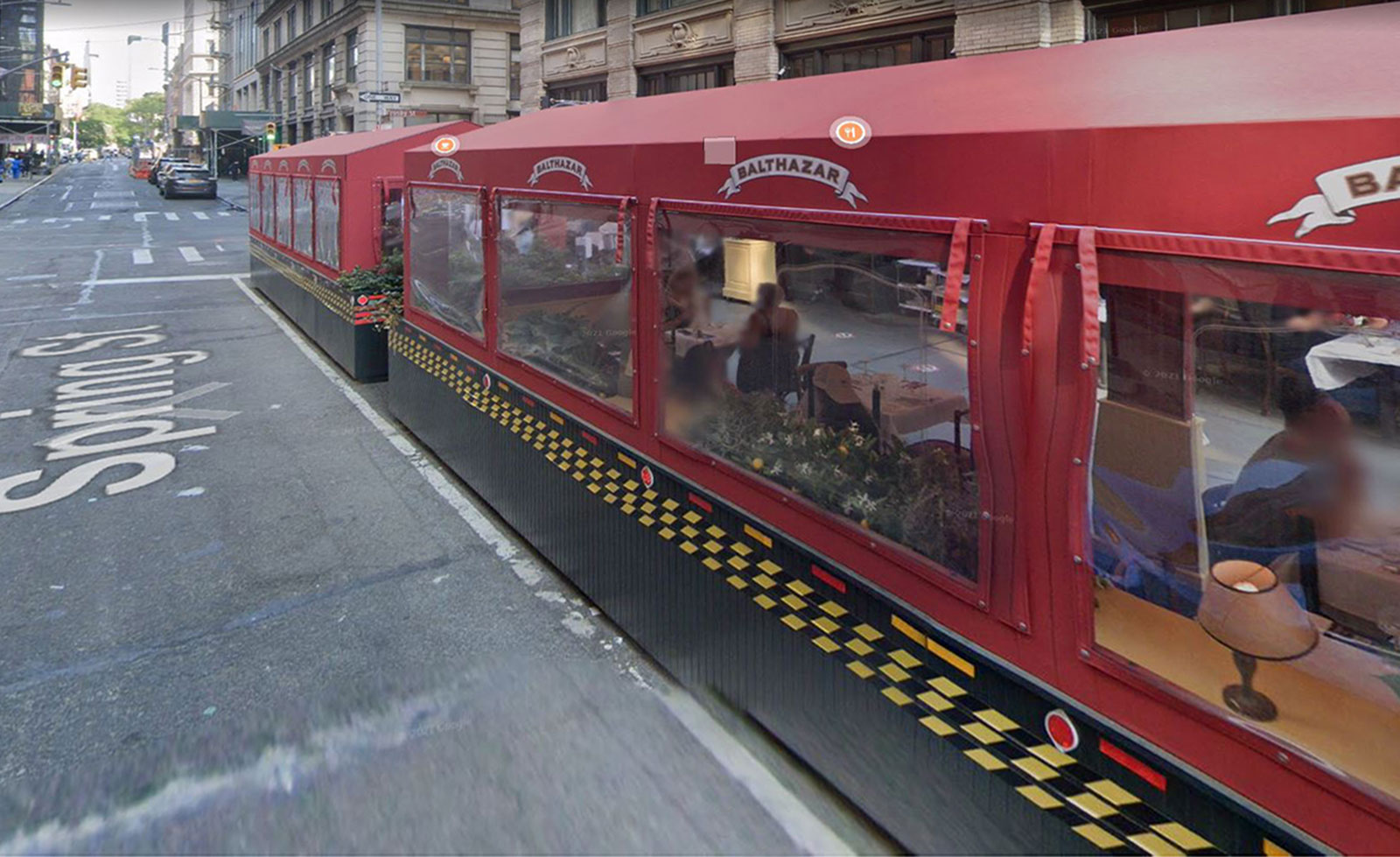

It didn’t take long for us to notice that many of our favorite establishments had indeed fallen victim to the financial and social challenges posed by the pandemic. Eating and drinking establishments celebrated for their interiors and design savvy were hit hard, as it’s difficult (or impossible) to replicate these experiences via curbside pickup or outdoor dining shelters—also known as streeteries and open restaurants. Of the many survival stories we encountered, this article about the beloved Prune in the East Village encapsulates the struggle best. Smaller, brick and mortar retail shops were also disproportionally hit, and the scene of dark-glass-clad empty storefronts occurs uncomfortably often along the once again busy streets of Manhattan.

But there is an urban silver lining to the Covid catastrophe. At the risk of being accused of donning rose-tinted glasses and shellacking a glossy coat of rainbow paint over a devastating situation, we couldn’t help but notice something that’s been missing from the urban realm for decades: mess—a hefty but productive mess along the sidewalks that encroached on the roads, stealing parking stalls, and mucking up the otherwise orderly street fronts. Seemingly overnight an entire population of makeshift outdoor dining shelters appeared in front of every restaurant and bar whose owners had the wherewithal, resilience, grit, and determination to get through this unprecedented situation.

Some of the outdoor dining shelters have clearly been designed, while others better fit into the category of amateur tree fort constructions; some are open and some have doors at each “dining room”; some have transparent roofs and others have roof structures more sound than the restaurants they serve. In the end, they’re all beautiful. The diversity, the ingenuity, and the complete mess of it all adds a layer of discovery and experience to the urban fabric that our cities need. These shelters activate the sidewalks, coax people outside, and demonstrate that good company and delicious food are all it takes to create a wonderful experience. With any luck, this experiment is also teaching us that décor, opulence, and the newest playlist aren’t as important as we previously thought.

Additionally, the forced trade of parking stalls for eating and drinking space is brilliant and lovely; until necessity and survival stepped in, the strategic coopting of automobile amenity for public enjoyment space was a slow and incremental battle among urbanists. Yet with one fell cataclysmic swoop, entire street fronts banned vehicles and invited humans in. Now, because these areas are so enjoyable and exciting, it’s difficult to picture a scenario where we would once again concede to the car.

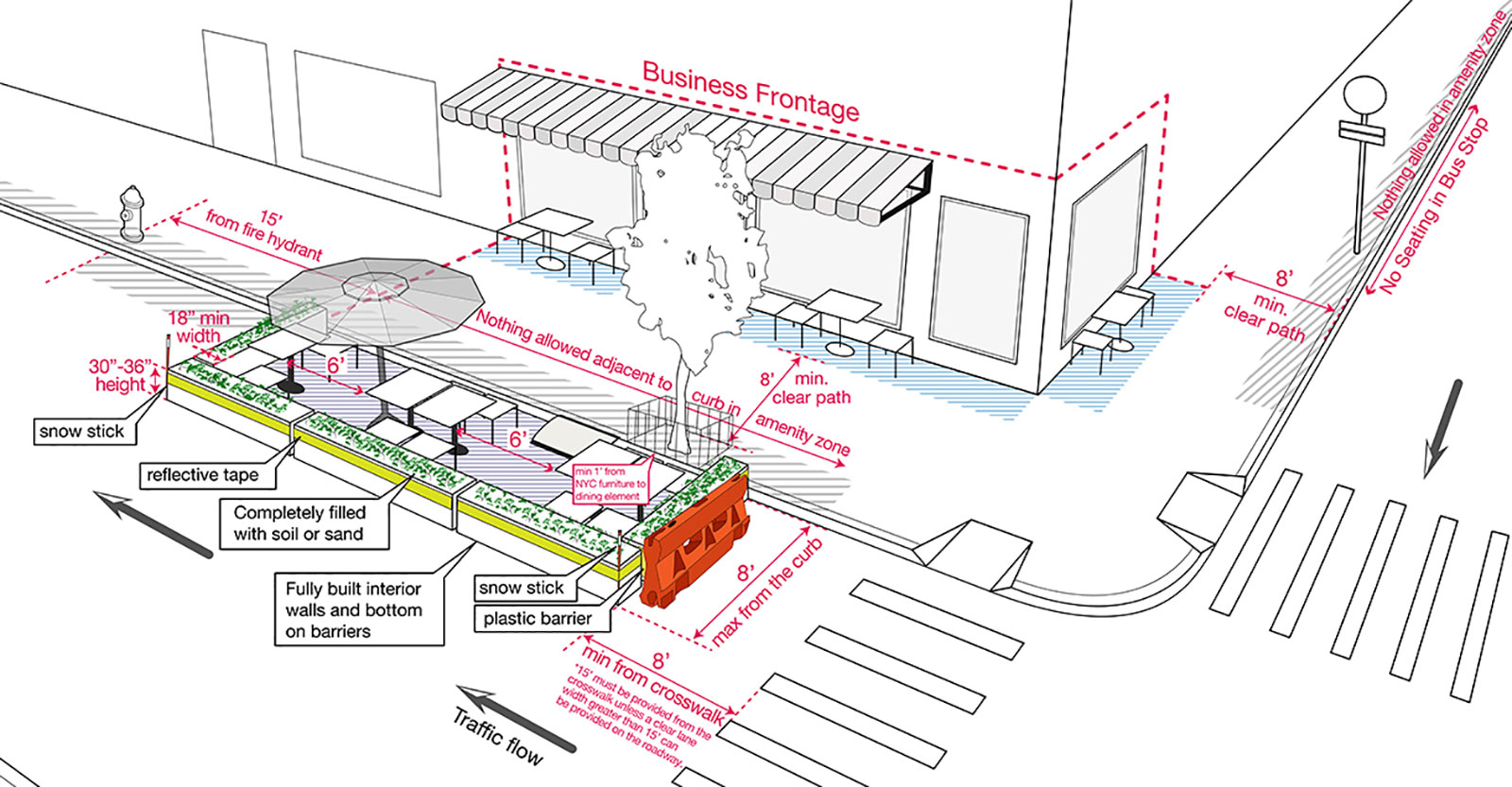

Best of all for architects, this situation proved that building departments can work quickly, efficiently, and from a spirit of effective problem solving when the issue is critical. Maybe all of the outdoor dining shelters in Manhattan are permitted and the city is keeping a careful account of them; maybe some or all of them are flying under the radar and the city is simply turning a blind eye in these difficult times; and maybe this situation is temporary and has an expiration date. The point is, this condition proves that building departments can be flexible and accommodating when they need to be; we have to believe that the directive from the top must have been: Get it done or else. While we can only imagine what these conversations looked like, the results are clear: no several-months-long permit submittal timelines, no endless permit correction cycles, no permit fees so inflated that they sabotage the very project they claim to serve. Just an environment of getting shite done.

It’s difficult to know how this culture of outdoor dining shelters will evolve with Covid variants, building codes, health and safety protocols, and social behaviors, but it’s enough for now to simply acknowledge the wonderful mess of it all. Our cities need more spontaneity and improvisation; more creativity and scrappiness; more quirkiness; more weird.

So, to the restaurants, bars, cafes, brick and mortar storefronts, mom ‘n’ pop shops, and every other business type that’s putting grit and unconventional thinking into solving this new set of challenges in the built-environment, thank you! We appreciate the mess of it all.

Cheers from team BUILD