Ten years ago BUILD got to know Jared Della Valle at the Reinvention 2011 event in Phoenix, Arizona. We were astounded by his bandwidth, professional diversity, and architectural accomplishments. We subsequently sat down with Jared in Manhattan, where we got caught up on his architect-as-developer model, and working in the then new economy. Part II of the interview can be viewed here.

You have masters degrees in architecture and construction management from Washington University; you are a licensed architect in the state of New York; and you hold a real estate license. What triggered you to tackle such a wide range of professional endeavors?

I can’t say that I’ve had an explicit trajectory—I did carpentry and furniture building in high school, and I have always worked hard. I decided that I wanted to work for a builder, so I found this crazy guy in New York City who was an architect’s builder. Tod Williams gave me his name, and he built stuff for people like Henry Smith Miller, and all of the good architects. I worked with him for five years, and I built some wild stuff, like Ian Schrager’s apartment, which was a $4.5 million renovation completed in ten weeks—a very high-end, $1,000 per-square-foot project. And it was one of those situations where we could only work between Memorial Day and Labor Day — we couldn’t do construction any other time — so there was no missing the window. It was a great exercise in learning how to build, and the more high-end work I was doing, the more people trusted me. Subsequently I took on more important work and a greater diversity of roles on the jobsite.

What were your first projects like? How did you get off the ground?

I was so young, and none of my clients had money. I did small stuff, like working for family members of my business partner at the time, Andy. His sister hired us to do an addition, and I also did work for myself. In New York City it’s so hard because most jobs are interiors—to get a new building is impossible. In construction management school, I had to take two business classes; one was accounting, and the other focused on how to write a business plan. So I was working at the construction company, and started doing our own work. We were on our third interiors project, and I was thinking to myself, this is not what I want to do, this is stupid. I don’t want to do interiors, I want to build something in the city. And I didn’t want to wait.

As an architect, you can’t look for work; you have to wait for people to find you. But I decided that I wasn’t going to wait any longer, and I started spending all my nights looking for real estate. It was before the internet was prevalent, so I would walk around and look at buildings, and then I would have a broker approach the owners of ones that seemed viable. My broker was older and looked the part, and with him in front of me, no one ever knew how young I was. So I just started putting offers on buildings, and I would force myself to write business plans for the deals.

When an offer would come in, I’d tell them to send it to my attorney, who was a friend of mine; I’d tell him to just sit on it while I wrote the business plan to get the cash. I’d get it all wrong because I never took any real estate classes. I was using all the wrong words, and I didn’t know how to underwrite it. I didn’t know how to do any of this.

Did you get the wrinkles ironed out by the time it went through your lawyer?

No, I actually never had him review anything because I didn’t want to pay for his services.

How did you avoid getting screwed over in these deals?

I didn’t get anything done for years. I spent all my time networking with people, telling them that I’ve got this deal and would they like to invest? I explained that I’d do the architecture, which no one ever questioned. I just threw it all out there, and I’d meet people I knew who worked for banks or whomever. And over time I figured out how to write a pro-forma. I’d ask for examples of projects that impressed people, and I’d work it all backwards to see what the numbers should look like. I’d reverse engineer the Excel spreadsheets.

But you learned all that while getting paid, right?

Yes, as the architect. I was young, and it didn’t matter. I wasn’t married, I didn’t have any kids. Over time I started to hone my presentations—I was learning what worked and what didn’t. And I also started to learn how to ask for a lot of money. What are the pitfalls, what are the important questions, what do you give up?

How do you ask an investor or a bank or an organization for a large sum of money?

The person that you’re most likely to get the money from, you share the deal with last. You learn from everybody else exactly what is wrong and what questions you should be ready to answer, so that you’re ready to ask somebody who is actually going to write the check. You start seeing when people are interested, and you learn that great deals are very easy to finance, and okay deals are very hard to.

Your current projects are measured in tens of thousands of square feet, yet you’ve worked with smaller scale projects, like your 1,100-square-foot R-House in Syracuse. How do you effectively shift gears between large and small projects?

The small stuff we do now has to be personal to me. Projects that we take on now professionally have to be millions of dollars or I’d rather just give it away to non-profits.

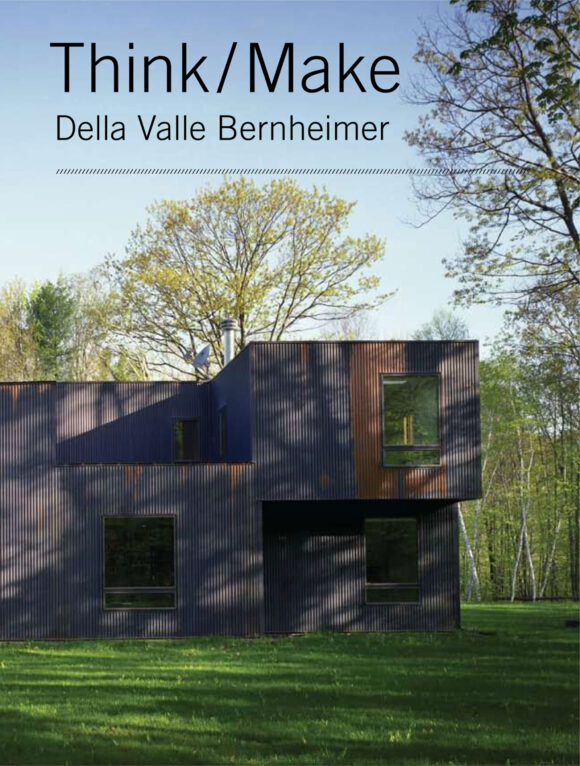

You recently released your book, Think/Make, published by Princeton Architecture Press. What did you most want to convey to the world with this book?

The message I wanted to get out to the world is: be resourceful in whatever you are doing. If you don’t have the resources, figure it out. Ask a lot of questions. Go for it. Don’t worry about failure. There’s no other way but to get out there, be scrappy and get it done. Nobody is going to do it for you.

I’m currently writing my will for my kids, and at the end of the day I’m going to have an estate that’s worth something. But I don’t want my kids to grow up feeling like it’s theirs. I’ve got crazy stuff in my will, like dollar-matching for when they save money. If they want access to the cash, they can propose a business plan to the trustees, and the trust will pay for business advisors to help them get there and review the business plan. Basically, they can’t just have the money—at least not until they’re older. Until then, I’ll pay for all of their education, but I’m trying to teach them that they need to have goals and a meaningful career choice that they’re passionate about and work hard at. And if they have a great idea, I’ll support that. It’s impossible to teach work ethic. If you’re in your 20s or 30s and you’re unmarried, my advice is to work hard. You don’t have to get home early. You can balance having a social life and working really hard. You can focus on career choices and making long-term decisions.

I’m currently writing my will for my kids, and at the end of the day I’m going to have an estate that’s worth something. But I don’t want my kids to grow up feeling like it’s theirs. I’ve got crazy stuff in my will, like dollar-matching for when they save money. If they want access to the cash, they can propose a business plan to the trustees, and the trust will pay for business advisors to help them get there and review the business plan. Basically, they can’t just have the money—at least not until they’re older. Until then, I’ll pay for all of their education, but I’m trying to teach them that they need to have goals and a meaningful career choice that they’re passionate about and work hard at. And if they have a great idea, I’ll support that. It’s impossible to teach work ethic. If you’re in your 20s or 30s and you’re unmarried, my advice is to work hard. You don’t have to get home early. You can balance having a social life and working really hard. You can focus on career choices and making long-term decisions.

When you first started out in New York City, you considered yourself to be an outsider. How did being an outsider benefit your career?

Going to Washington University and moving to New York, my business partner Andy and I had no network. But it made us feel like we had something to prove. It made us scrappy. We didn’t know anybody anywhere in New York City, so we just started attending everything.

Your Glenmore Gardens housing project in Brooklyn was constructed for $127 per square-foot. How on earth did you build good, modern design so cost-effectively in New York City?!

There was a request for proposals aimed at developers, and we submitted as developers with no experience, and as architects. All the other developers just copied stuff for the RFP they submitted the last time, whereas we treated ours like a design competition. We did a lot of work up front and a lot of drawings—most of this stuff we would normally give away anyway. And the City said, OK, let’s see what happens. The City has all of these crazy design guidelines, and we broke every one of them. The buildings had to be brick, the cabinets had to have raised panel doors, and we just fought them on everything. We said: the intent of your rules is to make sure that affordable housing meets a certain quality standard, so we’re going to prove to you that we have good intent and are interested in good design, and as a result, you should give us some latitude. We demonstrated that their rules weren’t really applicable, and at the end of the day they let us do whatever we wanted because we proved our intentions.

We tried so hard over two years. It was a labor of love. We found one of the affordable builders and we convinced him to do this project for $110 per square-foot. There was only about $20k worth of change orders on the entire project. He did a great job, but we drove him mad. It was incredibly rewarding, and the units still look great. People take care of them.

Jared Della Valle has been a real estate professional and architect for more than 15 years. He is President of Alloy Development LLC, a real estate development company he established in 2007 with partner Katherine McConvey. He has been involved in many significant projects, including 192 Water Street in Brooklyn, 459 West 18th Street in New York City, Glenmore Gardens Homes in Brooklyn, and 245 Tenth Avenue abutting the High Line.

Jared Della Valle has been a real estate professional and architect for more than 15 years. He is President of Alloy Development LLC, a real estate development company he established in 2007 with partner Katherine McConvey. He has been involved in many significant projects, including 192 Water Street in Brooklyn, 459 West 18th Street in New York City, Glenmore Gardens Homes in Brooklyn, and 245 Tenth Avenue abutting the High Line.