[Images courtesy of Studio Mumbai]

In 2011, we spoke with the wise and insightful Bijoy Jain of Studio Mumbai. His practice in India, now in its 26th year, integrates architects and skilled craftspeople to produce work that is culturally significant and responsive to the environment. Replacing traditional drawings with consideration, communication, and physical models, Jain’s extraordinary work investigates a new process of architecture. We hope you enjoy this conversation from our archives.

You received your master degree in architecture from Washington University in St. Louis, then went on to work in Los Angeles and London before returning to India in 1995 to found your practice, Studio Mumbai. Can you tell us a bit about what it’s like practicing architecture in such different cultures?

In Los Angeles I worked in Richard Meier’s model shop—my position was similar to an apprentice, or a carpenter. This was a very different experience from practicing in London, and later in India, where I was an independent contractor; for this reason it‘s easier to compare the differences and similarities between practicing in the UK and India. In the UK, one of the important differences for me was the amount of structure and formality within the architecture profession, which is very different from how architecture is practiced and made here in India. By contrast, in India most of the architecture and built landscape was developed without architects. Like the UK, working in Los Angeles was rigorous and disciplined, whereas in India it’s more chaotic. In India, yes and no are sometimes the same thing—in fact, the way you shake your head for each response is even similar.

We understand that you prefer to communicate on-site with scale models and gestures rather than with conventional drawings. How did this develop in your practice?

The difficulty with drawings is that they become instructions. I remember watching craftsmen on-site trying to build from my drawings, and I knew this was not right, just in pure, physical energy. The materials, the way they came together, it destroyed me to see the work carried out like this. I found myself giving instructions to craftsmen who knew more than I did. Their knowledge had been acquired over generations, and it was all about sense and sensibility gained through observation. And that’s when one realizes the kind of power that an architecture degree can convey. Anyone with a formal education, whatever it might be, wields a certain power that, in a way, supersedes any intuitive or sensorial thinking.

So I had to give up this position, and with it the idea of creating precise instructions for craftsmen to follow. Instead, I developed a non-linear narrative for each project, which describes atmosphere, experience, emotions, and connection to place. I believe, in some way, that this process becomes present in the work because the craftsmen are able to connect rather than merely follow instructions. A stonemason is not there to simply break stone and install it.

Models work well as a means of collaboration and communication; more people are able to engage and participate in the discussion; they inspire different points of view, and everyone teaches each other. Magic happens when different people work together, finding common overlap. For me, this is a much less resistive way to work, and it yields better results. The work is done directly, and I have to connect with many more people, but for us, it works really well. We discover so many things that we were completely unaware of, and part of our studio is engaged in looking for places that are unfamiliar to any of us. Unexpected.

Bringing dignity to people and places is a strong belief of yours; how does this dignity develop in your work?

This aspect has also evolved out of the idea of power. It’s the human condition. I had an interesting experience a couple of days ago… Not far away from where I live is an intersection where there are some plastic structures just off the road — the type of structures you might imagine in a disaster situation, maybe four or five feet tall and no more than six feet long — just big enough for two bodies to inhabit. I’ve been driving past this space for ten years and thinking, “My God, I’m an architect! Surely there is something I can do about this.” But how do I do it? How do I start a dialogue, and how do I intervene in a way that I can be of some use with the skills that I have? And on this particular day I said, “I’m going to do something about it,” and I stopped on the way back from a site visit. There was a man and his wife out in front of one of the shelters. He was immaculately dressed in a crisp shirt, crisp trousers, and a stainless steel wrist watch. She was dressed in a beautiful turmeric-yellow sari, had thick black hair and wore jewelry. We spoke for a bit. They’d been living there since 1994 [17 years at the time of this conversation] when they had received the land for free.

As an aside, there were 15 of these plastic shelters, and the nearest public bathrooms are a half-kilometer down the road. The inhabitants all came from the same village in southern India; they spend half their time here and half of their time back in the village.

The couple work as plasterers for buildings and make decent salaries (it’s not unusual to discuss such details in Indian culture). We’re currently in the thick of the monsoon season, and it’s quite intense, so I asked them about the rain and their shelter, and the man said that as fast as the rain comes, it goes away. He said the plastic is tight and doesn’t allow a drop of rain in. He kind-of looked at me like I was stupid for needing the nature of plastic explained to me. We continued talking, and he said that they get ready each morning outside, typically beginning at 5:00am, because by 6:00 or 6:30 people start traversing the road and it doesn’t look good for them to be preparing for their day outside while people are going by. It’s a public space.

Do you see the reversal of empathy here? They are considerate to random people; they’ve formed this idea that it is undignified for them to get ready at 6:00 — both for themselves and the passersby — so they get up at 5:00. This idea of dignity is part of their DNA. When we think of this man as just a plasterer, who lives in a tent that we wouldn’t consider to be anything, we’ve just dismissed and destroyed the potential that lays within him. This was an eye opener for me because I was wanting to do something to help, and I was, in a sense, slapped in the face. It’s not about being happy or unhappy, or me thinking that I could contribute. These people are completely in control. This idea of dignity gives empathy to everything that surrounds us, whether it’s people, landscape, the ground, or materials. This relationship is very critical, and it means that you have to remain open at all times. This is what dignity is to me. Relationships. This was a good example of people, architecture and dignity.

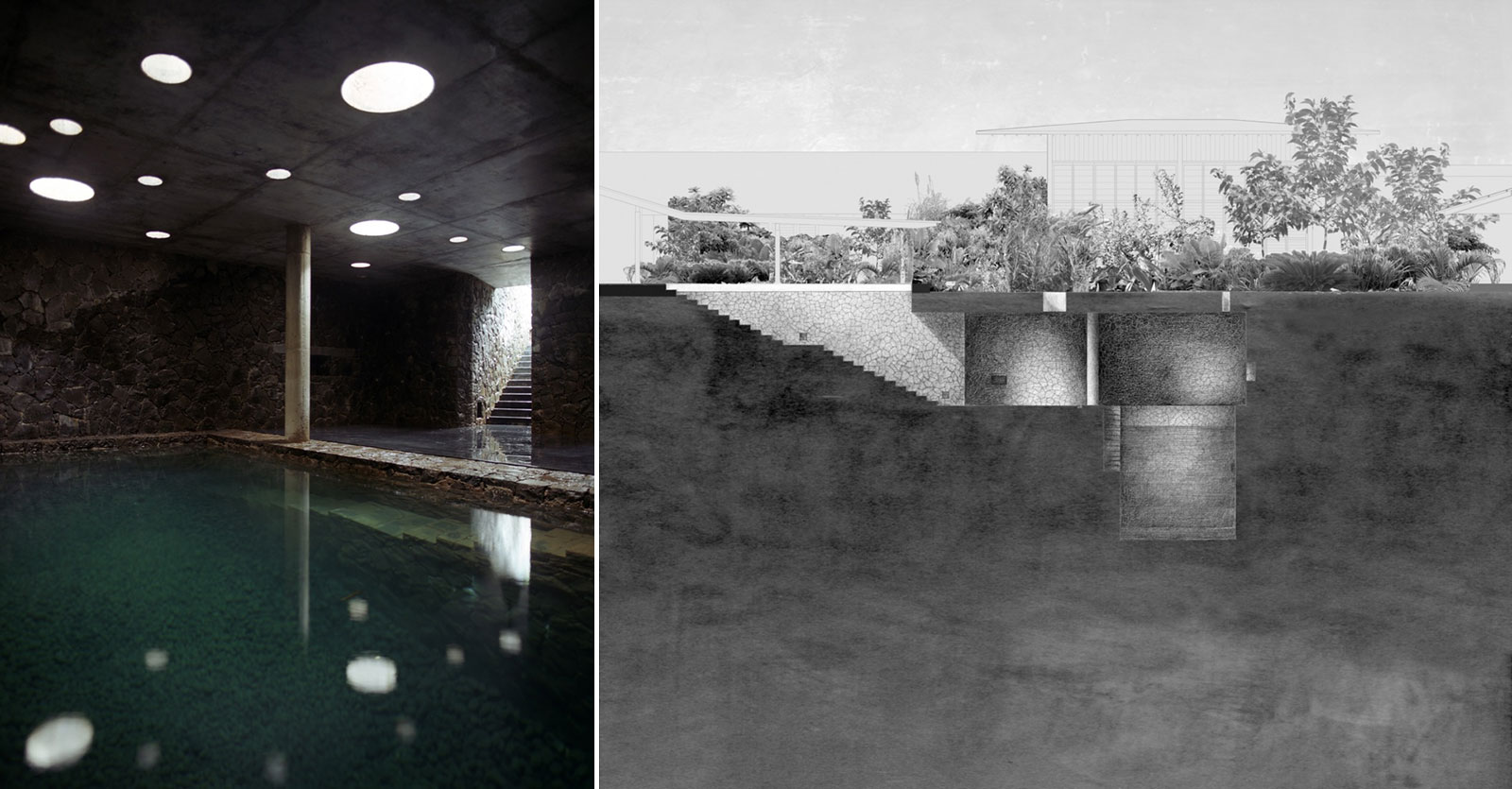

Much of your work deals with the immediacy of the natural environment; for instance, the constant flux of the water level in the Tara house pool that you designed. Can you tell us a bit about this project?

The Tara House includes an underground well of “sweet water,” which supplies the home with potable water, and is also used to water the gardens. The sweet water is separated from the sea water underneath by a natural diaphragm; the level of the sweet water is directly affected by the sea level. We had a local master well-builder out to the site who told us to dig only to a certain point and not go beyond it; if we did there was a possibility that the two waters would meet, in which case the sweet water would be contaminated by the salt water. It’s such a small, fine line. The situation was about putting faith in others and in nature with regard to this threshold of how far down you excavate. If you take this example of water, there is a certain amount of care or empathy present. It’s about knowing how far to go and then letting the situation rest, allowing the condition to work.

This seems to be just as much an attitude about human mindfulness as a solution to environmental circumstances, no?

Often in my work, the way I approach a project is as an idea rather than a structure. It is an understanding of how to navigate the different forces of nature— what can be beautiful can also be aggressive and ugly. Nature always has several sides and you cannot take one and not the other. It’s a careful negotiation.

The origin of water is important to the philosophy of your designs. Can you speak to the paradigm shift this brings about for the inhabitants of your work?

Most of India, even now, has to go to its source of water—the water doesn’t go to them. By going to the water source, whether it’s a river or a local water tank, you develop a relationship, which is essential to the evolution of architecture. It’s part of accepting the inconveniences that are part of the experience. You can’t say that you’ll only have the good and not the bad.

What have we missed? Is there anything you’d like to touch on that we haven’t brought up?

To me, what’s important in my work is the notion of empathy I’ve discussed, and giving up the sense of power that we all carry. Working with unpredictability is difficult for me, but it’s one of the things that I’ve recognized as worth keeping; it’s very important because it doesn’t tolerate the status quo. When I think about living and working here in India, what saves us as a country, as a group of people, is the chaos. If things were structured, I think we would implode. There would be no room for any movement. That’s the only way so many of us can co-exist; it would not be possible if everything was very precisely structured. It would be absolutely impossible to function.

Studio Mumbai, founded by Bijoy Jain, is a group of skilled craftspeople and architects who design and build. Their endeavor is to show the genuine possibility in creating buildings that emerge through a process of collective dialogue – a face-to-face sharing of knowledge through imagination, intimacy and modesty.

Studio Mumbai, founded by Bijoy Jain, is a group of skilled craftspeople and architects who design and build. Their endeavor is to show the genuine possibility in creating buildings that emerge through a process of collective dialogue – a face-to-face sharing of knowledge through imagination, intimacy and modesty.