BUILD recently sat down with master architect Lorne McConachie to discuss educational design, growing critical thinkers, and the importance of scale. As our kids prepare to return to the classroom post-pandemic, this conversation felt more prescient than ever.

As someone who has spent the better part of their career thinking about the design of educational environments, how did your own K-12 experiences shape your thinking?

I grew up as the middle kid in a family that seriously valued education; my parents asked my siblings and me to do good work, to be better, to check our work, and then do it again. My father was a plumbing and heating contractor and an overall smart man who knew about the world; and my mother was a writer who was very involved with the equal rights amendment when it was taking shape. As a family we were actively involved in civil and women’s rights, and our dinner table conversations about world affairs were the best thing that happened to me. I have to believe that my critical thinking skills and lust for knowledge grew out of this foundation: a nice family that provided food, love, and prioritized civic conscious and action.

For many of us, critical thinking skills are a goal we have for our children—to gather information, to challenge it, and develop new perspectives. Our political landscape is filled with people who don’t have these skills; they don’t know how to process big issues like vaccines and coup d’états. One positive way forward is to teach our children to be serious explorers rather than mindless receivers. As I have thought about education as a pathway into the future, I’ve concluded that, in part, we need to develop creative opportunities for deeply understanding how we can create spaces that support critical thinking. And we need to reshape how we instruct.

As a kid I attended lovely K-12 schools, but they had double loaded corridors with classrooms on either side, a Prussian military model for how to organize space, which is about efficiency and sorting rather than learning. Instead, let’s work to create educational spaces that allow for meaningful engagement and collaboration.

What are some of the architectural missed opportunities in K-12 design of the past?

Scale. If I’m not an assertive kid, when there are 600 other kids in my elementary school, or 1600 in my high school, I’m not going to establish a personalized connection with my teachers or peers, which would likely draw me out of my shell. So it’s challenging for me to emerge from the background. Part of what we’ve been working on in educational design is creating small learning neighborhoods or communities where children feel a strong sense of belonging.

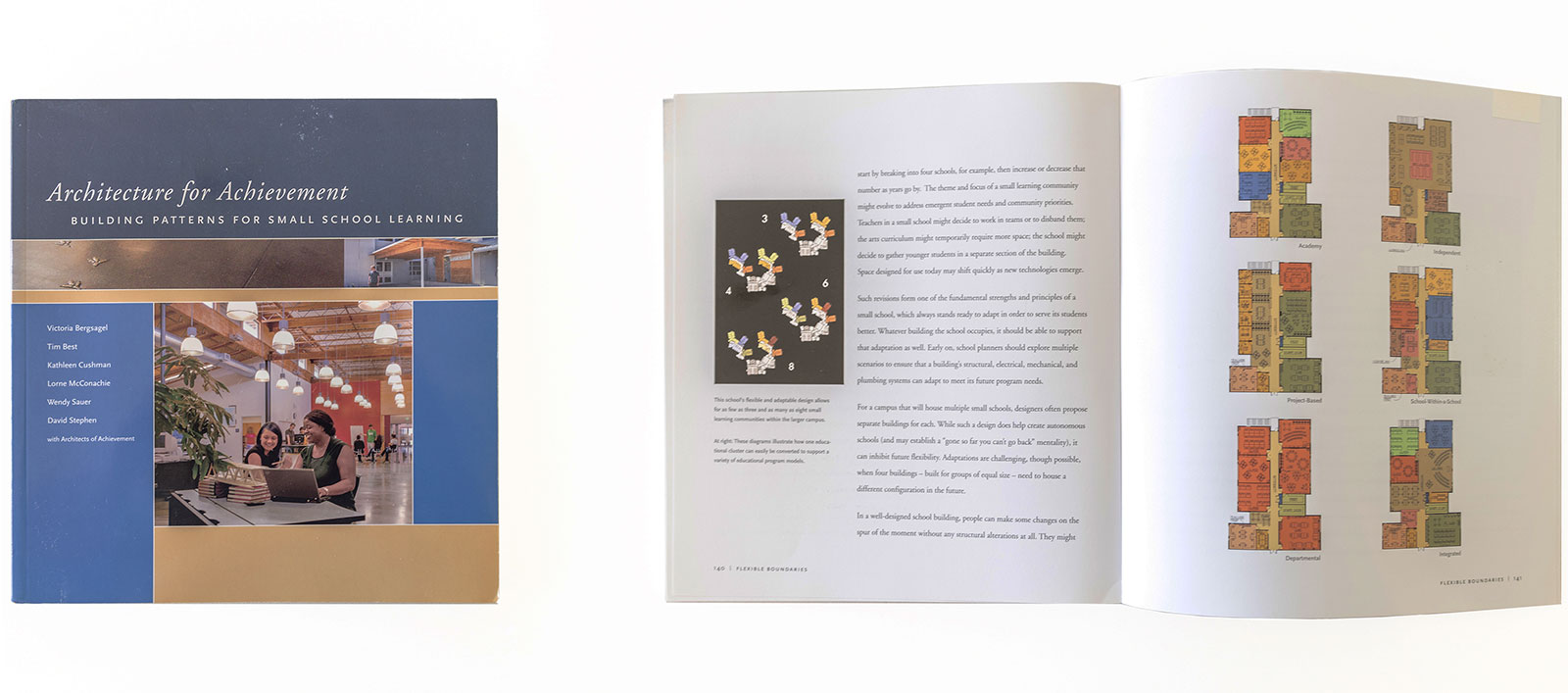

Was this the impetus for your book, Architecture for Achievement, Building Patterns for Small School Learning?

Yes. This book came about during an interesting time when a number of people and institutions had been doing research into what shaped powerful learning communities and found scale and personalization to be important factors for success. Research by the Gates Foundation also recognized that learning within a personalized environment led to greater student success, so the Foundation proceeded to make a strong push to fund and develop small learning communities. One of the challenges we discovered in writing the book was how to apply the research on personalization and scale to public schools where management and financial constraints are often impediments to change. So, I’ve been interested in developing models of smaller learning communities within the constraints of public school programs.

Throughout the Covid-19 pandemic, educators have been in a state of reaction; considering this, how are you now thinking about the design of educational spaces?

There’s a prodigious amount of stasis in how things have traditionally been done, which doesn’t allow for easy change. I’ve been pushing against this for thirty years and have seen some incremental change, but nothing significant—though the opportunities are tremendous. For example, individualized learning on a mass scale is now an option — such as with Kahn Academy — and the ability to learn when ready, anyplace, anytime, is powerful. There was a great study done in England in the last decade where a bunch of kids were dropping out of school for one reason or another, and the researchers developed a system where kids could go online any time of day and access a tutor—some teachers were in North Carolina and others in Siberia. The kids who participated in this form of remote learning started doing better than those who were attending a traditional school because they were getting just-in-time learning, or instruction exactly when they were ready.

Recently I’ve been focused on trauma-informed-design. Coming out of the pandemic, 90% of children are dealing with some form of toxic stress, 40-60% of which is traumatic. When we’re traumatized our emotions are no longer engaged, and as a child, I’m no longer capable of making critical thinking leaps. Our brains function in nuanced ways: reptilian survival skills—warmth, food, shelter; emotive impulses that allow us to connect with others; and executive functions that support critical thinking, which is what we hope our schools will sustain and nurture. As our kids return to school we have the opportunity for personalized learning on a scale we’ve never had before. Let’s not revert to old habits.

Steve Jobs famously said “People don’t know what they want until you show it to them.” In this spirit, what do you think students want — or should want — in their educational experiences that don’t currently have?

When you visit schools that are powerful learning communities, they look and feel different—the energy of the place is palpable, and kids who have typically struggled find pathways forward and are able to succeed. 15-20 years ago our firm was working with the Federal Way School District, including some very enlightened facility planning leaders who recognized they needed to change their mode of teaching. They had an alternative high school called Truman, and I traveled with that school’s principal around the country to look at various innovative education models that would suggest something different for Truman. We visited the Metropolitan School in Providence [now called The Met], the curriculum design of which was developed by Big Picture Learning. Upon our return she told her school board that she wanted to emulate aspects of Metropolitan and they said, “No.” She said, “I quit.” Long story short, after several rounds of back and forth, the principal got her way and turned Truman, a school with a 10-15% graduation rate, into one with a 97% graduation rate. Rather than having classrooms, students had advisors, each of whom were responsible for 10-15 students. The demands on the advisors were tremendous, which some thrived in and some didn’t but the increased engagement between teacher and student was a game changer. Implementing similar models within the public domain also demands an extraordinary client—one who wants to takes risks, and one who wants to explore in the service of finding the best solution for their particular school, and for their particular students.

Can you talk a bit about Practical Sustainability?

Until the mid-90’s, sustainability was a difficult word within many public school districts, but we knew we had to embrace it—we wanted to embrace it. So for every job, often behind the scenes, we would develop five new sustainably-minded ideas that we would integrate — such as the inclusion of sustainable materials or solar infrastructure — but to the client they would just look like paint (albeit a low-VOC variety) or systems. Finally, the dialogue began to shift and greater awareness and willingness to engage in a discussion around climate change emerged.

A former partner of mine developed a great analogy for engaging a resistant client in a conversation about sustainability: he suggested we think of them as a string that you can’t push because it will get all bunched up, but you can pull it along and into a dialogue. We make better progress when we ask our clients What do you really want? How can we save you money? How can I pull you into a deeper conversation around sustainability? I currently have young designers in my office who think it’s a fool’s errand, but I maintain there’s a fine but workable balance between pushing and inviting. An example is at Arbor Heights Elementary School in West Seattle where we designed and implemented the infrastructure for photovoltaics (PV) even though the final installation wasn’t in the budget; a year later the district received a major grant and asked if they had a school that was PV ready, and the grant was applied to Arbor Heights. We have to keep asking how we can shape our buildings so they’re poised to assume sustainable practices when the dollars are there. This said, we fully understand that school districts are faced with tough financial challenges, and that educating students comes first.

How important is the inclusion of play in a K-12 curricula?

In Coddling of the American Mind the author discusses the importance of unstructured play, which is critical—raw imagination engenders creativity, citizenship skills, negotiation skills, diplomacy, and so much more. Structured activities — soccer, music, dance, etcetera — are wonderful, but they don’t allow the student to spontaneously react to and debate any number of situations that arise during unstructured play. We really need to let our kids go out and play more.

You’ve noted the importance of listening in your work. How do you focus the skills of listening when the client is a community, a school district, a PTA, and hundreds of children?

With our projects we have broadly used a design team model where we invite representatives from our clients’ various stakeholder communities to participate; we explore guiding principles by asking everyone to share their aspirations, their goals, and their hopes and dreams for their new school. From this exercise, we develop an understanding of core beliefs and then use those beliefs as the lens through which we develop and critique the evolving design. By staying focused on the guiding principles we are able to develop authentic engagement and question long-held beliefs that can often become impediments to earnest change.

A district may only get funding to update their schools every 25-30 years, and in the meantime, the design of educational environments will have made advances that the district will have missed out on; is this advantageous from a design perspective because you will be able to implement all or most of these details? Or is it a disadvantage?

I would argue that a powerful successful school is the result of leadership, community engagement, educational vision, and a building that supports this, with the latter being the least critical. I’ve seen potent learning happen in dreadful spaces. Leadership is essential. One of the guiding principles that we regularly see is adaptability. We need to design flexibility into our buildings so they can accommodate inevitable change. We regularly use scenario planning to develop What if? options to ensure that our buildings will support a wide variety of approaches to learning.

In the 1970s architects struggled with the notion that architecture alone could solve social problems. Can the design of a school solve educational challenges?

No, I don’t believe the design of a school can solve its educational challenges, but it can provide flexibility in the environments that fortify their learning communities. A very wise client of mine once said to me: The building is not the change; the building allows the change.

What are your guiding principles for delivering the best educational pathways?

- Flexibility— short term change, such as furniture, room moveable walls.

- Adaptability—building systems change: structural, mechanical and electrical systems.

- Personalization—meeting a student where they are and what they need. Relationship with a caring adult.

- Collaboration—architecture studios, rather than the traditional classroom, are a good model for where education is going. Teachers need to be able to work together, to demonstrate collaboration in a meaningful way

- Evolving technology—embrace it, use it to better communicate and interact, and recognize that it will change radically every 5-10 years.

- Safety—how do we create place and neighborhood rather than control and supervision? If my teacher knows me well, I’m safer. This is important in an age when one out of four kids is bullied. If we can create meaningful learning communities, where the teacher and students all know each other and everyone is engaged and cared for, the bully factor will likely wane. We need to think more deeply about how to achieve a broader definition of safety.

Is there an audacious design outcome that you’d like schools to achieve that they haven’t yet?

Indoor outdoor connections in every school. There’s always a financially-driven concern, which I understand, but it gets back to our dialogue about play…the deep engagement with the natural world is critical—in addition to being instructive on a expansive scale, it’s also a stress reliever.

What is your least popular belief about education design?

The concept of personalization. As I see it, the way to get more kids to deeply engage is to take a personalized approach to instruction. Therein lies the key to the kingdom. Moving beyond 25 to 30 kids in a classroom is tough to achieve, and I’m constantly asking how can we create a more personalized learning environment. I’m hopeful we’ll get there.

Lorne McConachie received his bachelor of architecture from the University of Oregon and is a principal at Seattle and Portland based Bassetti Architects where he has cultivated a 36 year career of creating personalized, collaborative spaces that support differentiated learning, engaged communities, and sustainable connection to place. He has received local, national, and international attention for his approach to innovative school planning and design, and revitalizing historic schools as centers for 21st century learning. In partnership with several renowned educators, Lorne co-authored Architecture for Achievement: Building Patterns for Small School Learning.

Lorne McConachie received his bachelor of architecture from the University of Oregon and is a principal at Seattle and Portland based Bassetti Architects where he has cultivated a 36 year career of creating personalized, collaborative spaces that support differentiated learning, engaged communities, and sustainable connection to place. He has received local, national, and international attention for his approach to innovative school planning and design, and revitalizing historic schools as centers for 21st century learning. In partnership with several renowned educators, Lorne co-authored Architecture for Achievement: Building Patterns for Small School Learning.