[Photos courtesy of Will Bruder Architects]

In December 2011 we met with Will Bruder at the extraordinary Burton Barr Phoenix Central Library that he designed in 1989 in collaboration with DWL Architects+. He spoke about desert light, a strict budget, and what it’s like to work through the public design process of a civic building. Afterward, Will generously chatted with us to elaborate on his 40+ year journey in architecture. Note that since this interview took place ten years ago, Bruder has moved his practice to Portland, Oregon. We hope you enjoy this conversation from the BUILD archives.

You’re busy, yet you still made time to give us a personal tour of the Phoenix Central Library. How do you remain so accessible?

The person is the brand; sharing, mentoring, and navigating a dialogue are all part of the deal. In my own experience, I’ve knocked on very few doors that someone wasn’t kind enough to open. You never know what you’re going to get, sometimes it’s a five-minute conversation and sometimes it’s an hour, and sometimes a lifelong friendship. The act of engaging with people is necessary to the process of discovery. There are always unexpected results from each interaction, conversation, or experience; it’s less about knowing something and more about discovering something. The best work comes out of these investigations.

Years ago at a lecture we attended, you told the architects in the audience to “honor your clients, because they could have gone out and bought a house on a credit card.” What traits do you continue to see in clients who are willing to go on the adventure of architecture?

Their life experiences have shown these clients that architecture has something unique to offer. For them, architecture has the potential to be an armature for better living, so they are willing to take that step.

Most clients approach me not for a certain style or a dependency on what my portfolio looks like, but for the possibility of inventing something for them and their place; what matters to them is the process of design and how their lives will be changed by it. The first conversations with a client can be very honest. Recently, I was approached to do a 15,000-square foot house in Las Vegas, and I immediately dove into a conversation about the size. Was there a large family, a special circumstance, a collection of some sort driving the size? I wasn’t seeing my investigations resonate, so I quickly lost interest and the conversation ended. In order for me to take on a project, I have to respect the client’s values and dreams.

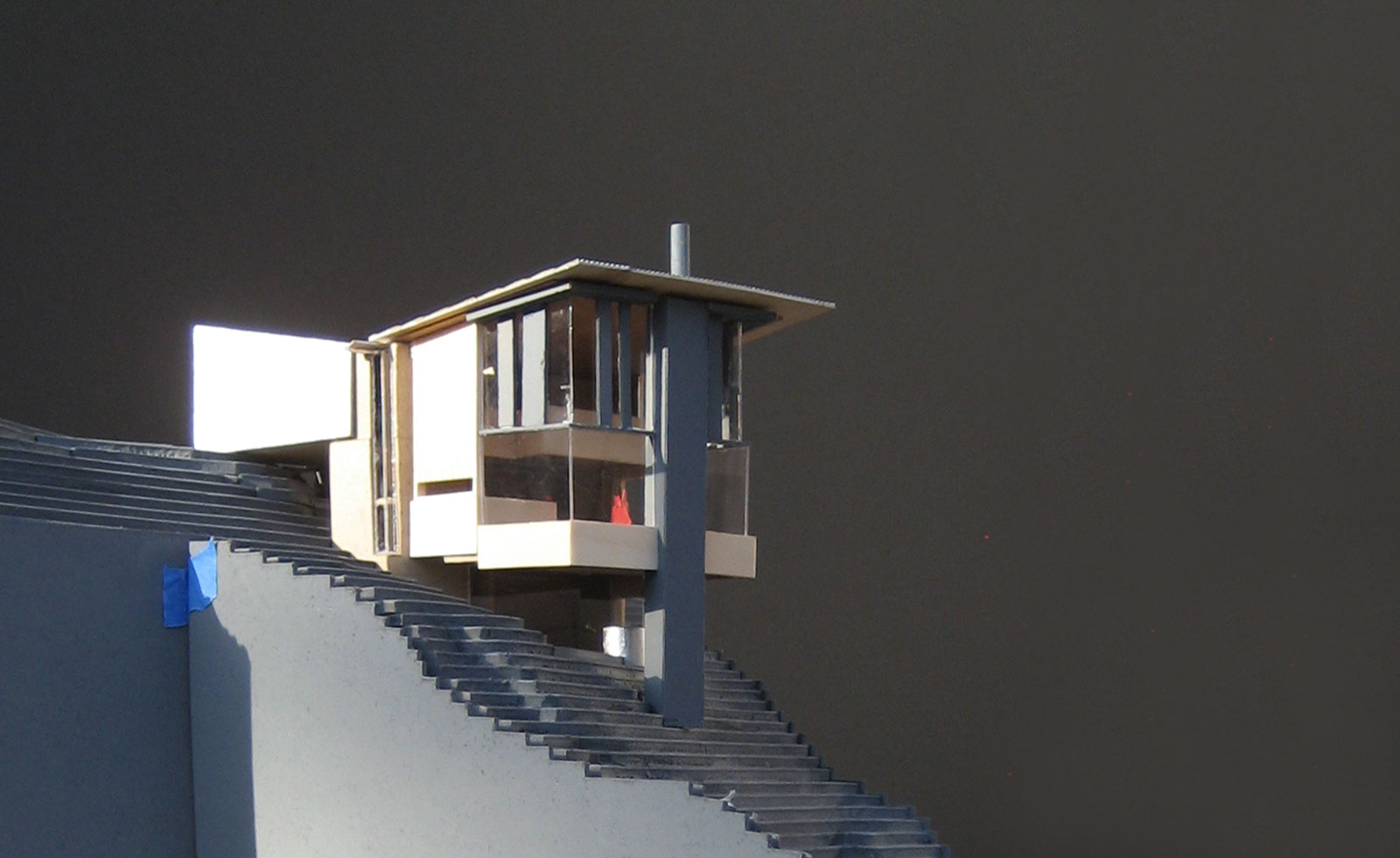

On the other hand, I’m currently speaking with a client about designing an 1100-square foot home on Lake Pend Oreille in Idaho. The client has a vision of doing something very special; it’s a modest little structure with two feet of lake frontage. I spent two or three hours with him to forward the conversation and to see if we would benefit by doing some architecture together. This project is as exciting for me as working for wealthy patrons in the civic realm of Riyadh.

As a self-trained architect and a teacher, you bring a fresh perspective to the nature of academics; are architecture schools preparing students to be good architects?

It’s challenging to teach architecture in such a way that students understand the spirit, poetry, and pragmatism of their art. We’re so fascinated with the computer and its software, often at the expense of the intellectual tools that should drive the pencil and the screen. Once you’re in line for the laser-cutter, so much of the potential design is already lost.

I teach based on my beliefs and the values that I find important. For me personally, architecture goes from mind to heart to hand. It’s a very direct process. With or without digital technology, the starting point is always the same: it’s still all about getting to who people are. And so it is with students; I try to bring different course studies to the curriculum and expand who they are. I ask them to get their heads fully engaged and their hands dirty. Focusing on the development of the intellectual tools allows a studio to work in a cooperative model and toward a common goal. It allows us to get somewhere that we’ve never been.

Given that your work is known for rediscovering form with each project, is it difficult to establish a standard set of details in the office?

The only thing standard is a belief in the possibility of making. It’s not about creating a set of standard details, but rather having an understanding of architecture and a respect for the craftsman. The detail comes after the tool, and it’s important to inquire about the possibility that each tool and material holds, and what each allows and inspires. This standardization becomes a way of thinking, a respect for materials, and a knowledge of the tools. My mantra is that I’m always interested in how the ordinary can become extraordinary. Ordinary materials are so often overlooked, and the key to making them extraordinary is in understanding them through fresh eyes.

We love that you designed a car wash—it doesn’t begin any more ordinary than that. How was it as a design project?

It was great! The car wash was an intriguing balance of function and idea. Interestingly, the architecture itself was 4th or 5th on the list after getting a clean car, good service, and so on. At the same time, it’s a perfect project for an architect to apply their skills to because the product follows the process. There’s also an entire design strategy around having a captive audience, as people have 10 or 15 minutes with nothing to do while they’re having their car washed. There’s time to socialize, look around, and buy tchotchkes. So we designed the retail component and it took off. We did a couple of these car washes and each of them did better in sales than those that weren’t designed by architects. These car washes have become iconic, and two even won awards for best car wash in America. Notably, there wasn’t an architect on the jury, it was all car wash professionals. I’m always intrigued by projects that have an honest sensibility.

Living and working in Phoenix, you’re at ground zero of the suburban sprawl crisis. Is there hope for the suburbs in America?

No, I don’t think so. I lived out past the edge of the sprawl for a long time, before moving back to the city. The habit of the endless drive just isn’t a sustainable model if we value our time and quality of life. Architects belong to the city, not to the edge. Our studio moved into an old, repurposed building that was a former dance studio right in the center of the city. We have small residences and businesses as neighbors. We are part of the urban fabric. Perhaps the suburban crisis can be mitigated by some repurposed strips, which can form nodes of activity and identity. We have all the freeways we need. Let’s fill in the areas in between and not blade any more desert.

How is downtown Phoenix doing?

It’s a complicated puzzle. Every city is tied to political cycles of two or four years, and unfortunately, most modern auto-centric cities are not concerned with the pedestrian scale. Despite the political variables, I made and over 40 year commitment to Phoenix. I, and many others, worked hard to make the central core a 20-minute place, where by foot, bike or public transit you could meet all your needs and live a full life.

It’s been said that the age of the high-rise is over; apparently that’s not the case in your office, though, as you have several on the boards.

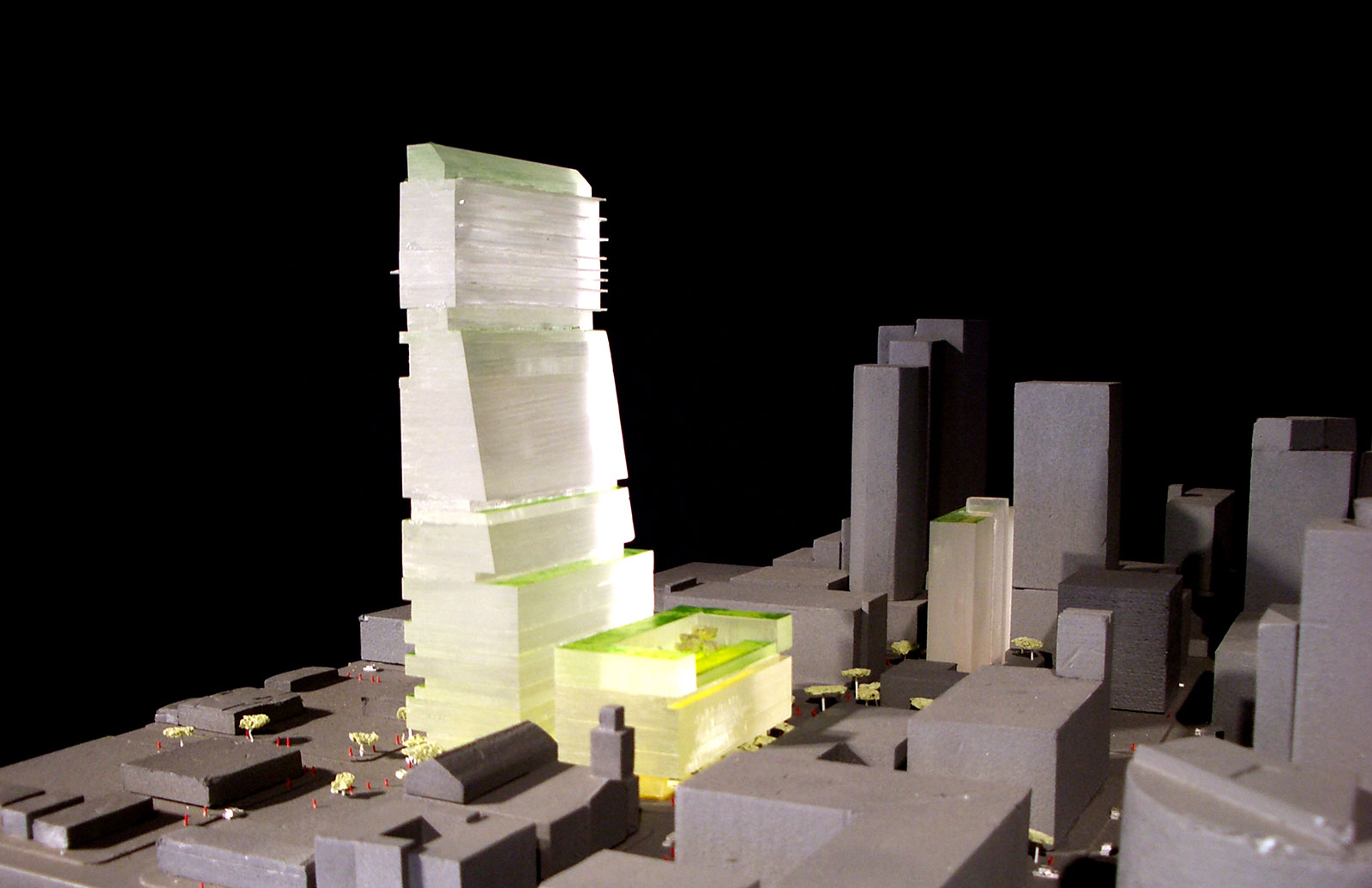

A tall building is still an iconic marker that has the power to define the skyline and a place. There are a handful of high-rises that remind us of the power and beauty of this building form. With the design competition for the Tatweer Towers in Dubai, we asked ourselves what it means to be iconic in Dubai. We wanted to present an attitude of social change and sustainability, and understand how a high-rise can honor its place. [The commission went to Burt Hill, now merged with Stantec.]

With the increasing level of programmatic requirements, City bureaucracy, and building code regulations in the architecture profession, how do you advocate for keeping the poetry in the project?

It’s important for architects to understand that the building code is only there to protect life safety, and that you can appeal anything in it—the introduction even states this. You can’t feel bound by the building code, but you have to understand it; you can’t challenge the rules until you know the rules and why they are there.

Years ago we had a project in Tempe, Arizona where we actually appealed and changed the building and zoning codes simply by continuing to ask “why not.” We embraced the democracy of the building code process and we proved our case. It worked because people want to be part of an idea. You have to take the building code on as a challenge and realize that there is a place for collaborative conversation and change in each project.

Do the design review boards and public meetings often associated with public work pose a threat to the invention and wonder of the architecture?

No, they’re never threatening. The review boards and public meetings empower the poetry, wonder, and beauty of a project. The town or city is coming together to do something special and part of our job as architects is to listen to and educate. It’s about opening up a dialogue and coming to these meetings with a sense of potential. Frankly, I can’t understand why we have so many mediocre buildings that don’t rise to the occasion. People love to see their ideas reflected in a design solution.

Will Bruder received a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Sculpture from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and took supplemental courses in structural engineering, philosophy, art history, and urban planning. He apprenticed under Paolo Soleri at the Cosanti Studio and Gunnar Birkerts. Bruder self-trained as an architect, obtained registration as an architect in 1973, and opened his first studio in 1974 in Arizona. Since then, Bruder has explored inventive and contextually exciting architectural solutions in response to a site’s opportunity and the user needs. His work celebrates the craft of building in a manner not typical of contemporary architecture. Through his creative use of materials and light, Will is renowned for his ability to raise the ordinary to the extraordinary. In 2019 he relocated Will Bruder Architects to Portland, Oregon.

Will Bruder received a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Sculpture from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and took supplemental courses in structural engineering, philosophy, art history, and urban planning. He apprenticed under Paolo Soleri at the Cosanti Studio and Gunnar Birkerts. Bruder self-trained as an architect, obtained registration as an architect in 1973, and opened his first studio in 1974 in Arizona. Since then, Bruder has explored inventive and contextually exciting architectural solutions in response to a site’s opportunity and the user needs. His work celebrates the craft of building in a manner not typical of contemporary architecture. Through his creative use of materials and light, Will is renowned for his ability to raise the ordinary to the extraordinary. In 2019 he relocated Will Bruder Architects to Portland, Oregon.