“Buy land, they’re not making it anymore.”

—Mark Twain

THE PREDICAMENT

Like many desirable areas to purchase land and build a house, the Pacific Northwest is in a predicament, a supply and demand predicament to be more precise. The region is surrounded by beautiful natural landscapes filled with mountains, oceans, lakes, and rivers. For those looking for a piece of the pie, the lack of available land for sale has exacerbated competition among buyers. Challenging sites that previously would have been passed up for a host of reasons, are now among the top ten under consideration. Land-Use codes and permitting requirements have dramatically escalated over the last decade, and what can — or more importantly, what cannot — be built is often difficult for a buyer to ascertain. At the same time, with increased competition, buyers feel pressed, which results in hasty decisions to waive contingency items, forgo inspections, or minimize the closing period in order to secure a property. More, sellers now have little incentive to disclose important and restrictive information about a property, as the competition leads to less scrutiny by potential buyers. “Let the buyer beware” has buckled under the desire to get some dirt.

THE SOLUTION

When implemented correctly, a feasibility study reduces variables, determines property viability, provides alternatives (if necessary), and allows the buyer to make decisions with confidence. This article will outline the process of searching for, assessing, and securing a property, conducting a feasibility study, and finally, closing on a purchase.

CURSORY STUDIES

While most consumers searching for property have a real estate agent on the case, only the savviest of them also have an architect on call. This is a huge advantage, as it allows timely evaluation of complex properties. It’s worth noting that the purchase of vacant land is a specialty that many real estate agents may not be well-versed in. Blank land is a different ballgame than buying a house and it may involve land-use issues, easements, and other critical items only found in the title documents. An experienced architect can help fill the gaps and can track down a wide range of information above and beyond the MLS. Some architects work on a retainer for these quick assessments, some invoice hourly, some do it to be considered for the future project, and others won’t touch them at all. It’s up to the buyer to identify the right architect and the commensurate incentive. When the right relationship is established between the property buyer and architect, the buyer is able to have their architect vet potential properties before they make an offer. These property studies are cursory, but a relatively limited analysis by an experienced professional short-circuits hours or days of time for buyers. Because these properties are likely being viewed by a number of interested parties, speed is key. If there are red flags, showstoppers, or other reasons to walk away from the property, the architect is able to determine them quickly so that the property may be dismissed. It’s important to realize that lurking among the available properties in the marketplace are some that are unbuildable (permitting or site construction activities that are just too expensive), which sellers may have difficulty determining or admitting. We’ve also seen our share of disclosure statements that contain negligence, errors, and glaring deceits. In the current market, vetting properties quickly and accurately is critical. Once a viable property has been identified, it’s time for the next step.

THE DETAILS OF THE OFFER

When a property has been vetted through a cursory study and appears to meet the buyer’s goals, an offer should be made promptly; if it is accepted, competition from other potential buyers is removed from the equation. The earnest money is deposited and the terms of the sale are established. Getting the seller to agree to an extended contingency period (due diligence) is essential. The period between making an offer and closing on a property should allow enough time for a feasibility study to take place. Somewhere between 30 to 45 days is typically enough time, but this may vary from property to property depending on the sites’ complexities, response times from the building departments, and availability of consultants.

THE FEASIBILITY STUDY

With an accepted offer and a healthy contingency period established, the buyer and architect have sufficient time to perform a comprehensive feasibility study. Because a thorough analysis requires weeks (or months) of the architect’s attention, and relies on a design team’s depth of experience, a buyer should expect to pay for this work; the old adage you get what you pay for couldn’t be more applicable to the feasibility study. You don’t want your architect informally doing this on the side as a favor. This fee may be the most valuable investment a buyer makes in their project.

Because each property is different, the focus of a feasibility study will likely vary between one parcel and the next, but here are some typical feasibility study tasks:

- Site visit and in-the-field information gathering.

- Coordination with relevant consultants (surveyor, geotechnical engineer, civil engineer, arborist).

- Municipal Code and Building Code study and documentation.

- Initiating a Preliminary Assessment Report (or equivalent) from the local authority.

- An exploratory land-use meeting with the building department.

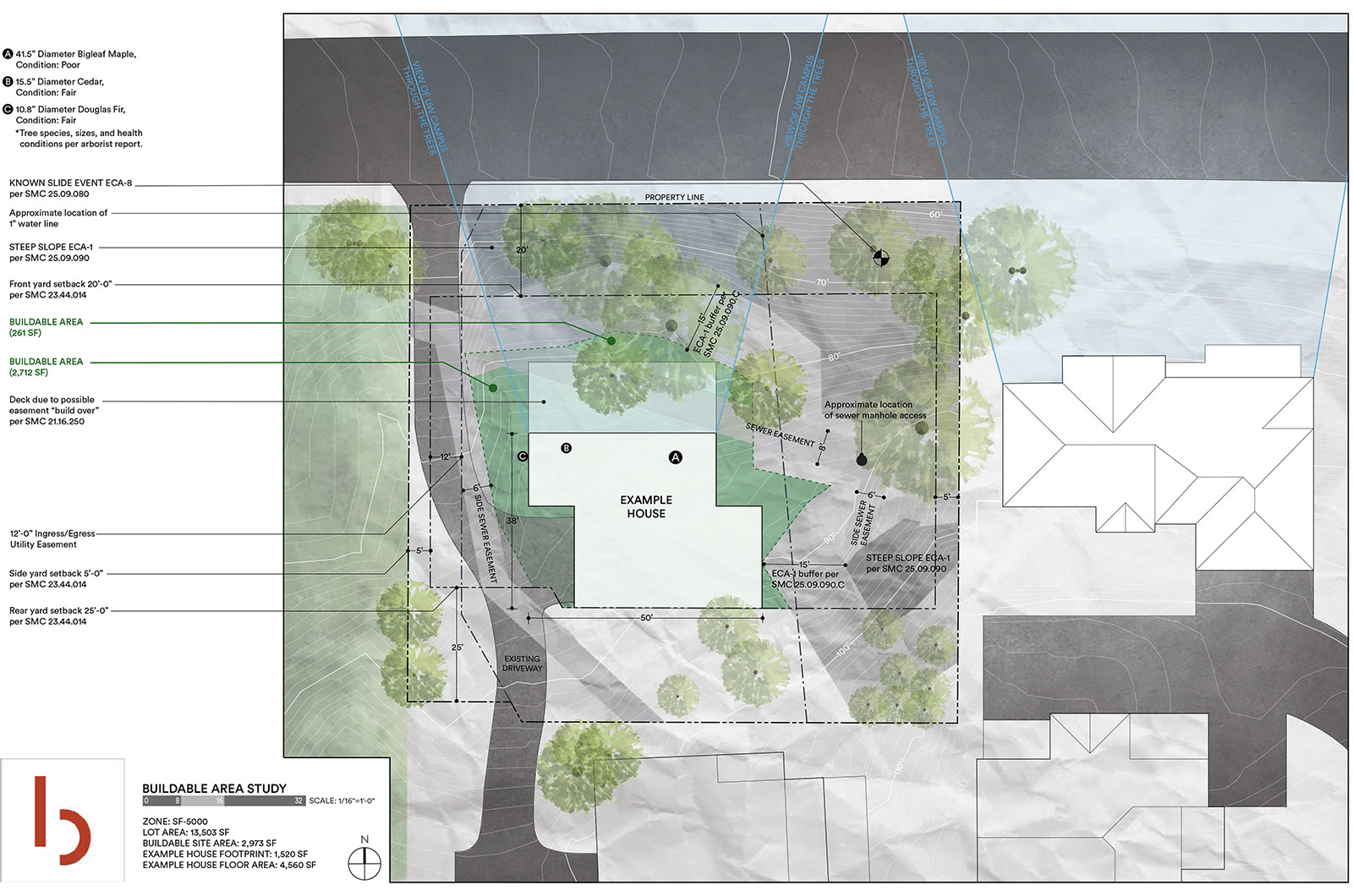

- Develop a basic site plan, documenting the environmentally critical areas, setbacks, utilities, and other land-use criteria.

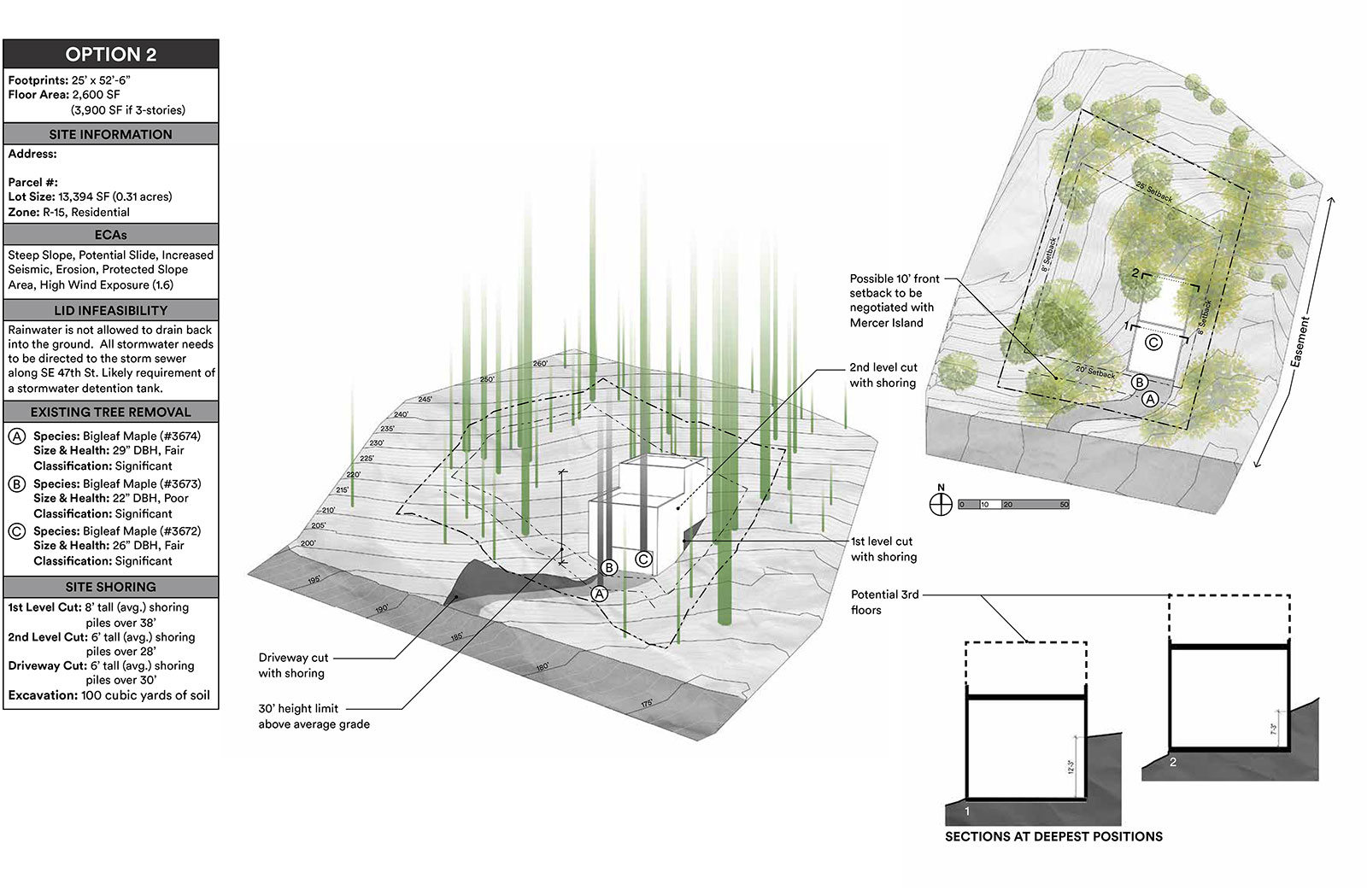

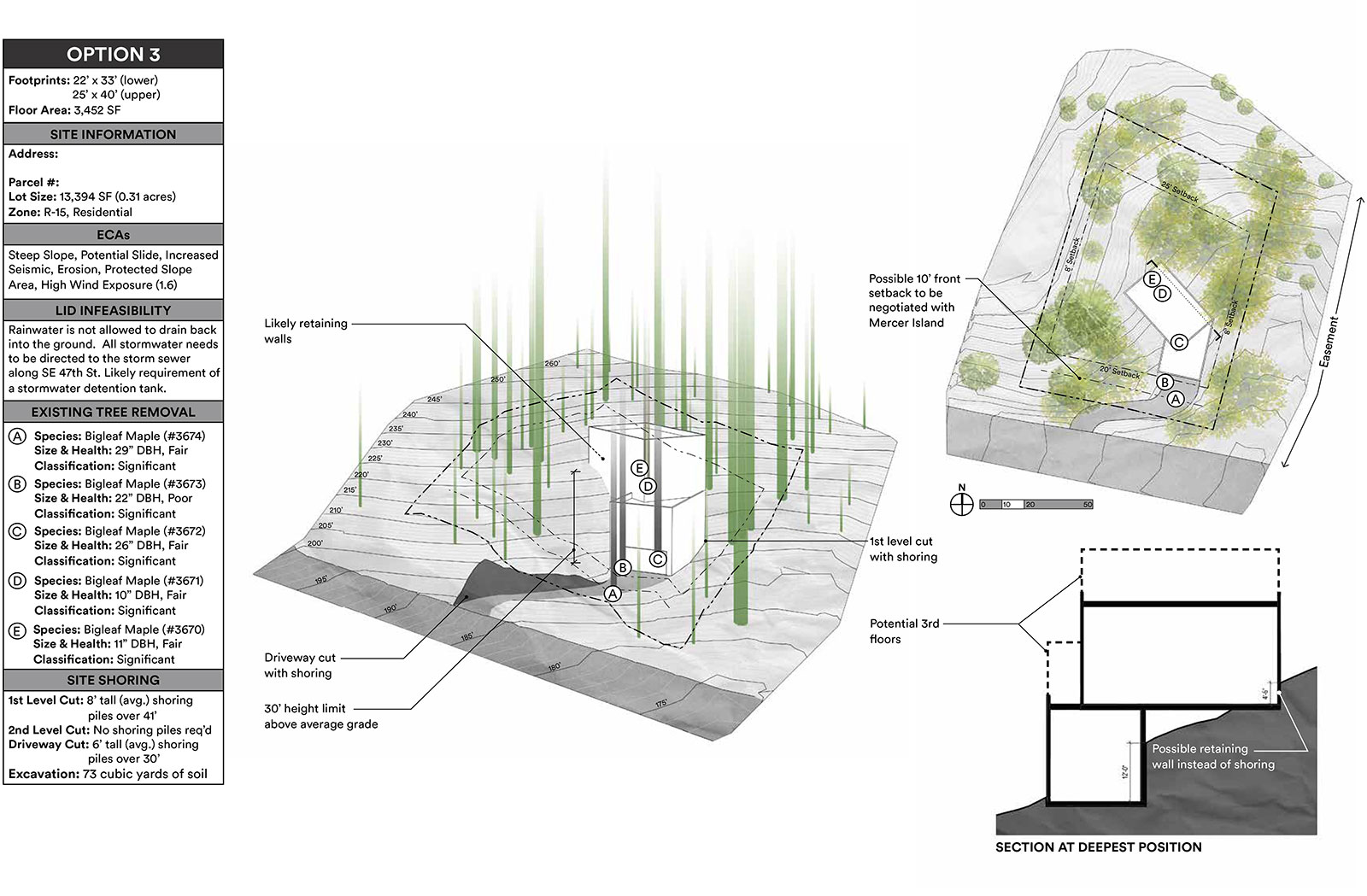

- Generate two to three building diagrams that respond to the site plan, code provisions, and program desires.

- Establish a rough order of magnitude (ROM) construction cost.

- Generate a preliminary schedule for the design, permitting, and construction of the project.

Some of these items may not apply to a particular property; others may have sub-categories or additional action items depending on a property’s characteristics. While there is no single boilerplate for feasibility studies, each have the same goal: a thorough analysis of the property to determine whether the project goals are achievable. In the event that the primary objectives cannot be met, a good feasibility study should outline possible alternatives. In the worst case scenario, limitations or unseen conditions that would prevent the project goals from being realized are identified. While this scenario is infrequent, the relatively small fee for the feasibility study saves hundreds of thousands of dollars in land costs, and months of pointless work.

FEASIBILITY STUDY DEEP DIVES

There are a couple of critical tasks within the feasibility study that deserve further explanation. For example, at the top of the list in the Pacific Northwest, there are environmentally critical areas (ECAs) to contend with. As mentioned in the introduction, the scarcity of available real estate in today’s market has led to increasing demand, which in turn has led to a greater supply of previously deemed undesirable parcels. These often include one or more ECAs, such as steep slopes, potential slide areas, known slide areas, shorelines, wetlands, streams, liquefaction prone areas, wildlife habitats, and significant and/or exceptional trees. While each jurisdiction handles ECAs differently, many of them can be dealt with and effectively accommodated when identified early. A rare few cannot be permitted effectively, and because the seller may not understand the ECA limitations, they don’t properly disclose this information at the time of sale. The feasibility study defines all ECAs and the most effective permit strategies to clear them. Identifying these ECAs will also provide a savvy real estate agent with the proper leverage for further negotiations that favor the buyer.

In urban and suburban areas, there’s also a healthy list of land-use and zoning considerations that are critical to identify and plan around. These include the zone itself and what is and isn’t allowed within it; whether a project is located in an urban center; determining any zoning overlays that may apply; adjacency to state or city parks (yes, this can have an effect on a building permit); Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) requirements, which may impose additional development fees (even for single-family homes); impact fees (for local schools, transportation systems, etc.); and equity areas. Some may not apply, but those that do very likely have compounding effects on each other.

More than ever, it’s useful, if not necessary, to bring consultants on board during the feasibility study period.

- Surveyor: By conducting an official topographic survey, a surveyor can determine if steep slope exists, and if so, to what extent. Easements and other site features should also be identified.

- Geotechnical Engineer: A geotechnical engineer can conduct on-site borings to determine whether soils flagged with ECAs can be built on, and if so, what is involved.

- Arborist: If significant or exceptional trees reside on the property, an arborist can generate a report that documents all tree sizes and species to get an accurate picture of the permitting requirements.

- Civil Engineer: A civil engineer can provide critical guidance on what it will take to manage stormwater (among other benefits).

- Land Use Attorney: With extremely challenging parcels, a land-use attorney may be beneficial in helping to determine whether the project goals can be achieved despite difficult property characteristics.

The architect orchestrates, coordinates, and synthesizes all applicable consultants and their respective findings into a cohesive package.

Last on the critical task list is conducting a meeting with a planner from the jurisdiction. Once all relevant data has been collected and challenges have been identified, it’s worth presenting the information, early design, and project goals to a land-use planner at the City or County. They can provide feedback, answer questions, and clarify code provisions with authority and (hopefully) accountability.

COMPLETING THE FEASIBILITY STUDY

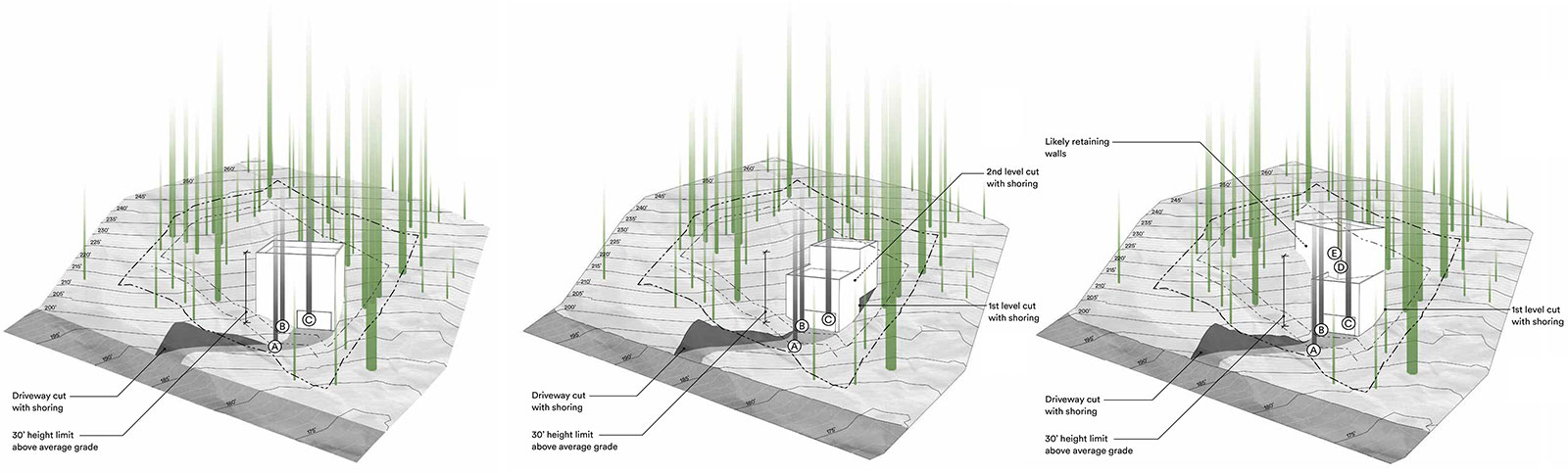

After completing the action items above, coordinating with relevant professionals, and reviewing the proposed project with the local building department, the architecture team will generate a summary diagram. This 2D or 3D visual encapsulates and clearly illustrates the site characteristics, code provisions, and constraints. This diagram provides the basis for building alternatives specific to the site. Think of these as basic clay models that demonstrate where structure(s) could be reasonably located, with the primary intent of documenting land-use conformance, elegantly.

CLOSING ON THE PROPERTY

The feasibility study effectively demonstrates how the project goals can be achieved given all of the factors outlined above. Armed with reliable data and a clear path forward, the buyer can now make confident decisions with regard to closing on the property. Depending on what the architect has uncovered during feasibility, it may be within reason to renegotiate sales terms, which the diagrams and documents can justify (and provide leverage).

THE OFFRAMP

If constraints are identified in the feasibility study, there is a possibility that the project goals cannot be achieved, and the alternatives are undesirable to the buyer. If the justification for pulling out of the sale is based on findings not originally known or disclosed by the owner, there is good cause for the buyer to be refunded their earnest money, and once again, the feasibility may be used as leverage to bolster the case.

MOVING FORWARD INTO DESIGN

With the property purchased, the feasibility study provides an excellent basis to move into the schematic design phase. While an architecture team may have a separate contract for design and permitting services, the feasibility study is an important component of this work and should be completed regardless. Most architects honor the feasibility study fee, which is typically credited toward their design and permitting services.

The step between the feasibility study and schematic design is also a decent place to take a pause if the new owners need to consider their options or secure construction financing. Alternatively, the owners may elect to consult with a different architect; in this rare case, the original feasibility study fee will not be credited or refunded, but nonetheless, the information provides very useful documentation for the project moving forward.

And then the design and permitting adventure begins…

Cheers from Team BUILD