An interview with Billie Tsien, TWBTA

by BUILD llc

Another interview from the BUILD archives, which we believe continues to resonate and inspire. Note that some of Tsien’s answers have been edited to reflect now past occurrences.

In 2011, BUILD sat down with Cooper Hewitt National Design Award winning architect Billie Tsien at her Manhattan office on Central Park South. Billie and her husband Tod founded Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects (TWBTA) in 1986, and have completed master works such as The American Folk Art Museum and the Neurosciences Institute in La Jolla. At the time of our interview, TWBTA was working on the controversial Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia. Billie graciously shared some of the behind the scenes process and thinking of their successful architecture practice with us.

Is there a sweet spot for size of an architecture firm?

A team of about 12 to the low 20s is a good number [note that today the firm has a team of 38]; with this size you can do anything. Everyone is directly responsible for the work of the firm, and are involved at all different levels of projects and have an understanding of their trajectories. The studio functions like an organism. Working here is a good education, nothing is hidden, and the staff can see what it takes to make a firm work. The people who work here are very committed.

What kind of breakdowns does the system inherently have? What are the breakdowns when it doesn’t work?

At times we’ll continue to design beyond our fee. We try to pick our battles and become clear about where it makes sense to continue and where it doesn’t. One of the hardest things you learn as an architect is what to accept and what not to accept. It’s such a relationship negotiation, and knowing when to stop designing is a potential breakdown for people new to the office who aren’t familiar with the balance we have. As a designer, it’s a personality mindset that determines how far you push people. We want to keep designing, but we have to have some kind of balance between time and money. At some point in a project you can stop designing, but that’s no fun.

How do you manage the work-life balance of architecture?

If you can’t balance work and life, you either leave architecture or you end up doing a bad job. How you run a practice when you become older is very important. Having kids creates a paradigm shift—you can’t get home at 9pm if you want to spend time with them. If there’s an issue at home, it’s the most important issue.

How were you able to sustain the growth, and the larger staff that you now have in down times?

We know that we can survive in a down economy. Over the last two years we’ve been busier than we’ve ever been. We’ve worked for institutions that have a certain amount of money set aside for new projects, and as a result, those projects are unencumbered by what the market is doing. In the last two years we’ve also offered our clients more construction value for their money.

How were you able to take on new project types without previous experience with that type of work, like a museum?

The client has to find the right qualities in you. For example, with the Neurosciences Institute in La Jolla, we showed the client some houses and an art project that we previously designed; based on that the CEO wanted to work with us. You show your most interesting work because it shows how you work. It doesn’t have to be relevant. It’s also important to show images that people understand—images that communicate the feeling of a place. This allows people to respond emotionally and intellectually to the work.

It’s commonly remarked that NYC architects rarely get to work on anything in NYC, but you’ve had the opportunity to design some very nice projects mere steps from your office.

Well, we were in our late 40s and early 50s by the time we completed our first projects in NYC. They were smaller projects, but they gave us the chance to focus on the detailing.

Do you think it’s more difficult to go out on your own as an architect in NYC than in other places?

It’s interesting that how you go into the practice varies depending on your location. I went to school at UCLA, and a lot of people I completed the program with began building immediately after graduation. Starting your own firm while you’re young is more of a west coast phenomenon. On the west coast the client base is typically younger, whereas on the east coast it is older and more established.

It seems that you’ve positioned yourselves well for institutional work.

I think so. I was at a dinner where the graphic designer Michael Bierut was relating some advice given to him by Massimo Vignelli. Massimo told him that good work brings in good work, and bad work brings in bad work. Generally, we don’t go after work that is speculative; those projects just need a different kind of architect, people who are more agile. We need to work with people who have values, recognize the longevity of buildings, and want to make some contribution to the world or the place.

Do you pursue work, or does work pursue you?

We’re generally asked to be on lists for certain projects, but it’s not as though people come to us and say: We love you so much that we think you’re the only firm for the job. I think when you do anything really well for somebody, word gets out. I think the issue of people being generally aware of a given firm’s work is good, but being too easily found isn’t necessarily the best scenario either. We don’t actively scan for potential jobs, and we don’t like competitions very much because we’re not very good at them. We do best with interviews with potential clients.

When you’re on the shortlist of a client who has sought you out, how does that process work?

Generally, we have to go to the client (rather than meeting at our office), and it’s usually the same architects being considered every time—some of them have prepared drawings and models, and others have incredible silver tongues. Now that we’re more experienced, we don’t actually think about who we’re talking to. The conversation is more about being who we are rather than catering to each project. When we talk about our ideas, we can’t talk about them in architectural terms. The ideas have to be presented in a way that makes them clear to someone who doesn’t understand a section drawing. How do we talk about ideas in a way that people will understand? Tod and I are different people, the way we think about things is very, very different; Tod thinks three-dimensionally, and I think much more two dimensionally. I feel that if potential clients can’t relate to one of us, they can relate to the other. The collaborations are healthy.

Have you found that you don’t want to share too much in the interview process because it’s easy for a potential client to form an immediate opinion?

I think our work is more experiential rather than made up of cognizant images. If we’re seriously being considered for a project, we like potential clients to visit our work. For us, design is more slow to come, more slow to develop. We also really believe that design comes from the process. Thom Mayne often goes into the initial interview with numerous physical models, and if that’s what the client responds to, there’s nothing you can do to change their mind.

It sounds like you prefer the client to sit with you, face to face.

Not everyone wants designers like us. Tod would say that it’s more important to know which projects to say no to. Life’s too short. It helps direct your practice. You steer yourself and know what is or isn’t right for you. It doesn’t feel good to be rejected, but a lot of times it’s okay—it’s just not a fit.

You won The Barnes Foundation commission based on a narrative rather than drawings or models. Can you discuss that a bit?

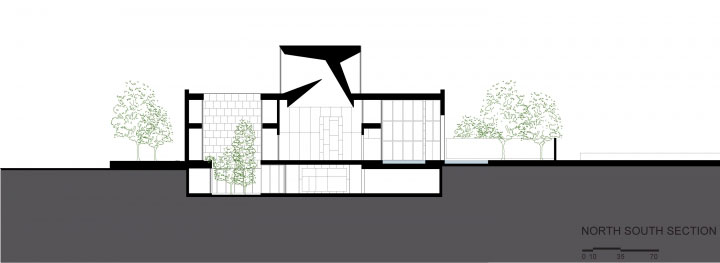

Our ideas were based on a simple diagram. The original site included a building set within a garden. When the Barnes Collection moves to downtown Philadelphia, the garden will be retained within the building, and gardens will be brought into the galleries. Strict parameters of the program prevented us from changing the plans, so our idea was to spread the building apart and insert gardens and classrooms between. The educational component of the Barnes Collection is also very important to us, and we want to retain it.

The decision by The Barnes Foundation to move the collection from suburban Pennsylvania to downtown Philadelphia put TWBTA in the crossfire of controversy. Do you think the architect is required to take a political stance on the issues, or are you able to draw a line in the sand and just concentrate on the architecture?

The downtown location and program carries the educational mission to people who wouldn’t be able to access it otherwise, whereas the suburban location [had] limited access and [was] therefore only a resource for people who have a car. I understand the specialness of a kind of house museum that’s tucked away, like the Wharton Esherick Studio, but that’s much more idiosyncratic. If you look at this collection, it’s one of the most important collections in the world. The fact that [it was] so hard to get to [was] a loss. The people who [took] classes at the [now former] location were mostly from a retired, well-to-do demographic; I think it’s good that the downtown location will open the collection up to more people—a more ethically and socially diverse audience. I think this is what Dr. Barnes would have wanted.

We understand that the restraints of the project were very detailed.

There were six architects considered for the project, and we all had to agree to respect the organization of the original building; the wall paintings need to remain in their respective locations and the sequence of the galleries has to be replicated.

How was the design received?

The design has weight and respect, but we expect to be criticized by people who feel strongly that the museum should stay where it [was].

What is your response to the criticism of moving the museum to its new location?

We couldn’t have done it if we didn’t believe in the project. We said no to a large project in India because of some ethical differences we had, chiefly that the project would be sucking up what little water was available to the community. There is a clear line for me. I deeply believe that the Barnes’ educational mission is fulfilled by moving the museum downtown.

There was quite a bit of news coverage about the American Folk Art Museum (AFAM) in New York; the institution sold the facility to MOMA, who may choose to raze it. How has this affected you?

Emotionally, this was very painful. We don’t do that many buildings, and this one is so important to us. MOMA owns the site to the west, and the AFAM is in the way of the development that Gerald Hines would like to do. If it’s torn down, it will be very difficult. There were articles that said the architecture killed the building, but today’s story is forgotten tomorrow. Architecture can only claim so much responsibility for the success or failure of an organization. The institution is also accountable. [As many of our readers will recall, the building was torn down in 2014.]

In wrapping up, anything we should have asked that we haven’t?

Tod and I were talking the other day: Why are we doing what we do? That’s a question I would ask. Who would I be if I weren’t an architect? It’s completely entwined with who I am as a human being.

Billie Tsien founded Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects with Tod Williams in 1986. Their work includes The American Folk Art Museum in New York, Neurosciences Institute in La Jolla, California, Cranbrook Natatorium in Michigan and the new home for the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, which will open in the spring of 2012. With Tod, she has received the Cooper Hewitt National Design Award in Architecture, among many other honors. Billie serves on the board of the Public Art Fund, the Architectural League and the American Academy in Rome. She is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. In 2007, she was elected a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.