A conversation with Gordon Walker

By BUILD LLC

A decade ago BUILD interviewed the Northwest master architect, Gordon Walker, on the topic of senior housing. It’s not hard to imagine that the design-minded senior will find it challenging to identify a planned community that feels like home. Today, COVID-19 has thrown the need for forward-thinking senior housing into sharp relief; our elders have been forced to socially isolate at a time when they need engagement — physical contact with family and friends — more than ever. In an age that is rife with technology and a pandemic that cause and demand social distancing, and a challenged healthcare system, relevant senior housing is a downright emergency. For these reasons, we thought it appropriate and inspiring to revisit the following conversation. We hope you feel the same.

The concept of modular construction and senior housing makes for a very specific project type. How did this come about?

I’ve been noodling on the idea of modular senior housing for a long time. I’m 7/8th of the way through my life now, and I’ve got to start thinking about a different way to live. I grew up in the modern era, and I’ve always recognized a hole in this type of living and designing. I can’t find anything in the senior realm that I’d consider dying in, let alone living in.

And this hole refers to the exclusion of modern architecture in senior housing?

The conversation is about living for tomorrow, not for yesterday, and what that means for our present state of living. The elemental concepts are based around community space, smaller spaces with multiple functions, and being able to walk to the grocery store or a favorite restaurant.

From what we know, you haven’t just thought about these ideas, you lived them.

My [former] house on Orcas Island is a modular system based on a 16’ grid. It generated enough interest on the island such that I worked out a modular system that would allow for multiple units — six to eight — which would be on one level for easy access. The 16’ x 40’ modules would equate to floor plans of approximately 650-square-feet.

[Photo by Andrew van Leeuwen]

The dimensions you worked with were presumably dictated by the method of delivery?

Exactly. A typical flatbed truck can accommodate a 16-foot maximum width. Interior functions, such as the living, dining and kitchen areas, are constructed together and shipped down the road to be set on pier blocks at the site.

What other hurdles did you encounter with the system?

Modular systems have a few drawbacks—where do you put everything that you’ve accumulated over the years in a 750-square-foot space? But the issue really boils down to an issue of lifestyle more than the belongings that folks have. Also, there are very few people in a place like Orcas Island who are familiar with the concept, and so they’re hesitant to give up their traditional views of housing.

A number of years ago I was involved with Unico Properties who, with design collaboration from Mithun and Hybrid, built and promoted two modular prototypes. You may have seen the units on display at the base of Rainier Tower in downtown, Seattle. The CEO, Dale Sperling, was given both units at the end of the project, which he tried to relocate to one of the islands as a personal residence, but the City of Bainbridge Island wouldn’t allow it unless he installed gable roofs on them. There are still some challenges with modular housing in the public.

That sounds just like Bainbridge Island. Aside from the cultural paradigm shift that needs to occur, what are the technical challenges?

The software used to fabricate the modular units is quite important. Because so many units could potentially be produced from one source, any problems with the software or the original template can be problematic. I’m finding some good shops, such as Gerding out of Boise, who have lots of experience in modular construction. There’s also a little shop on Orcas called Stem who build little tin boxes and one room sheds that could be used as vacation houses.

There have been many attempts at such prototypes from the shipping container angle—any thoughts there?

In a couple of past studies, we found that prefab containers are a bit more expensive than stick framing.

Senior housing seems like a very practical housing type. Given the theoretical direction that most architecture schools are heading, is it too practical to be taken on as a studio project?

A number of years back I taught a design studio at the University of Washington on modular student housing, and I introduced it to the students like this: With this economy and the way housing is going, you will probably never design a house for yourselves. The students and I didn’t learn as much as I’d hoped, but it was a fruitful think tank. Dave Miller, chair of the UW Department of Architecture at the time, invited me to do another studio, where I taught modular design, and it was more successful.

The only senior housing projects we’re familiar with in downtown, Seattle seem more like storage facilities (the one at Denny Way and Fairview Ave N comes to mind).

It is kind of like a parking garage for older people, but I don’t mind the density. Ralph Anderson, who I worked for in 1963, lived in the “Horizon House,” which is downtown. I used to visit him regularly when he was still alive. He designed and built five or six houses for himself in his lifetime, and he was very deliberate about where and how he lived. When you walk into the lobby of the Horizon House, you see great artists’ work all over the place, such as Jacob Lawrence and Alden Mason—it’s the place where sensitive artist-types live out their lives. The seniors at Horizon House are a good example of people who might want to live in something less traditional.

It’s kind of a shame to take the wisest individuals of our society and lump them all together in an out of the way location.

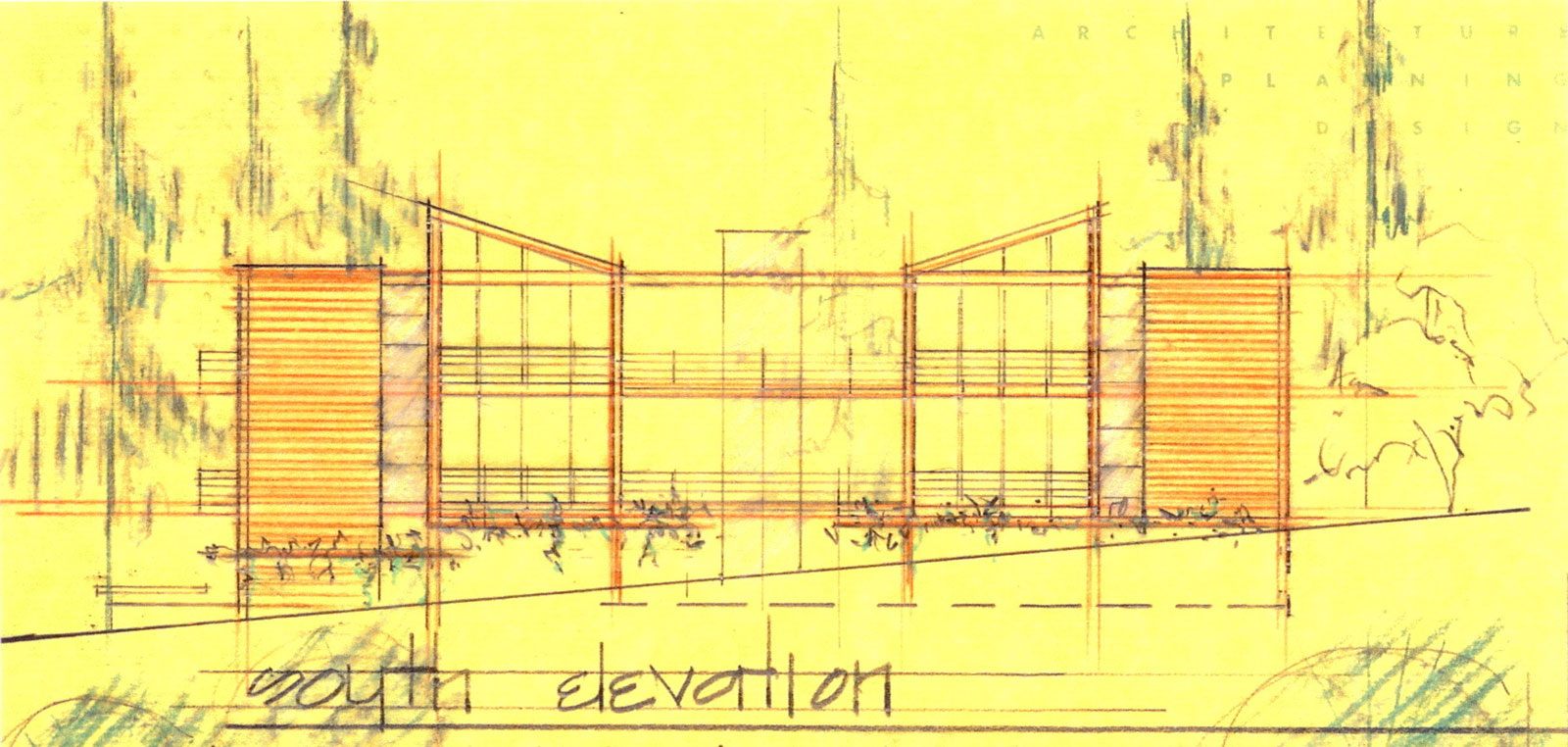

I can see a project like Nicholas Court, which I designed and is located on Capitol Hill, working well as a half-dozen senior housing units. It would make for a nice integration of younger and older demographics. The economics of building eight or a dozen units has its own set of problems, not the least of which is the City’s parking requirements, which quickly add significant cost to smaller projects. If the City would waive the parking mandate for senior housing developments, where every resident doesn’t have a car, it would make the project type much more feasible.

[Photo by Andrew van Leeuwen]

How about the general attitude around modular housing in general?

The only thing that has highlighted modular housing was the 2008 MoMA exhibition, but it was art rather than a practical display of housing.

Yeah, we attended. It should not have been promoted as a serious proposition for housing. If MoMA had called it “art” that would have been one thing, but the title of the show was Home Delivery: Fabricating the Modern Dwelling. Unfortunately, this is what’s driving the public perception of modular housing.

The mindset of modular housing hasn’t yet changed in America—people still want to over-customize the modular house. It needs to be more like a car. Owning property in common is also a big change for Americans. I was talking modular housing back in the late 1950s, and here we are, fifty years later, and we’ve done this [takes a pencil on the table and shifts it one inch]. We’ve still got a long way to go.

Whenever we see images of European senior housing, it’s always a gorgeous modern box, set within a pristine mountain landscape. Wouldn’t it be easier to just emigrate to Switzerland than to try and reinvent senior housing here in America?

You guys might be ready for that, but I couldn’t afford the ticket.

How is it that Europeans are so damn good at senior housing and America is so terrible?

They’ve had to deal with less space. I heard an interesting thing on NPR, and I’ve been incorporating this more into my own thinking; there was a study on the different cultures of the world, and one of the findings was that the Danes are probably the most cohesive culture on the globe. This is for several reasons: they’re well educated, they have a good standard of living, and they have good medical standards. It also concluded that the Danes are comfortable because they have low expectations. It’s totally different in America—when you come here you’re going to succeed and make it hell or high water. The Danes don’t have that. They understand the concept of “enough.”

We architects are always thinking about how we want to live, but how are we going to get the non-architects interested?

There are certain functions that are going to drive the movement—a desire for smaller houses that don’t require so much maintenance and cleaning, the efficiency of the space and ability to get around within it, proximity to goods and services, and living among people who can keep an eye on each other. It’s a lifestyle change, and modular senior housing is better than the alternatives. It allows for townships, which make more sense because you get to have neighbors around you, and you can walk to the café.

…and the modular senior housing typology could actually influence the rest of us.

Yes. There are two main audiences for modular senior housing: first, teach it to the kids because they can bring the concepts into reality in their careers [moves the pencil more than one inch]; and second, provide it to seniors because they need alternatives now. Then you can sandwich the rest [of the people].

Final thoughts?

What we are currently building is the memory of what was, the past, and it no longer works. We need to design and build for the future.