If I allow the fact that I am a Negro to checkmate my will to do, now, I will inevitably form the habit of being defeated. —Paul Williams

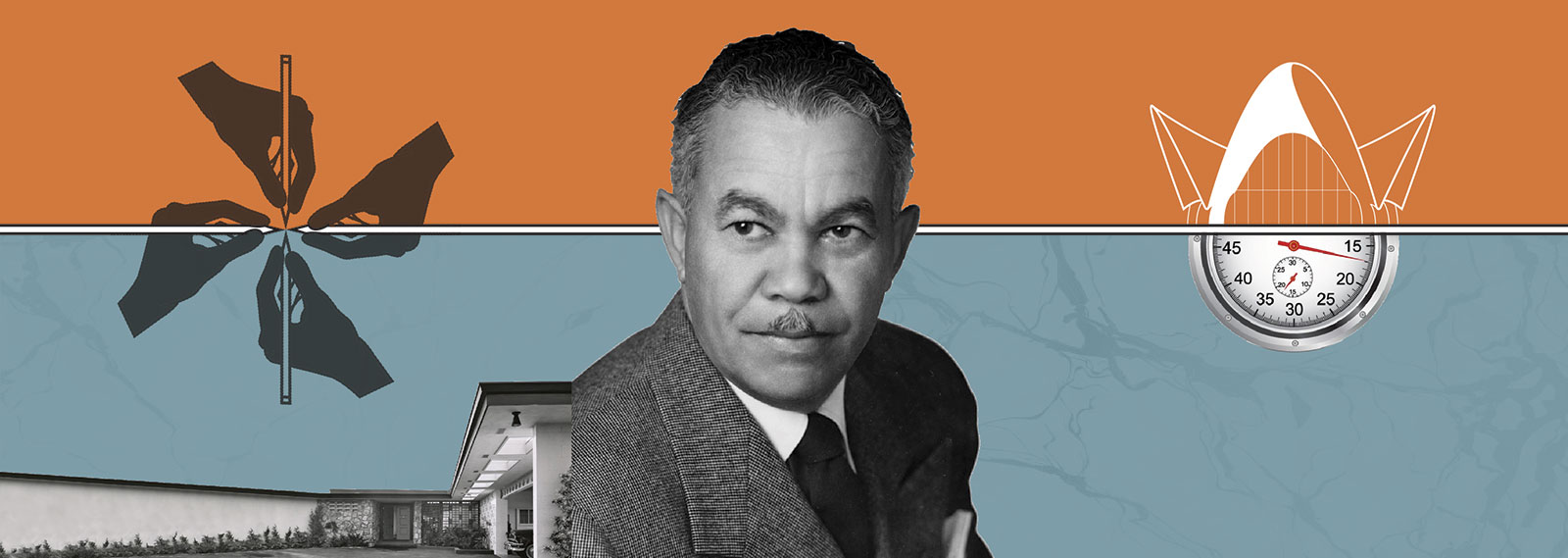

The ascent of Paul Revere Williams to master architect is one of the most inspiring and daunting accounts of any designer we’ve ever studied. The achievements of this immensely talented individual, who designed houses for the likes of Frank Sinatra and Lucille Ball, did not come easily. Williams was born in Los Angeles in 1894 to parents who had recently moved from Memphis. Orphaned at the age of three, Paul and his older brother Chester were placed in separate foster homes; soon thereafter, Paul was adopted by Charles and Emily Clarkson of Los Angeles. He attended Sentous Street School where he was the only black student in class, and his guardian mother dedicated herself to his education and artistic development. As he progressed through his training, he became increasingly interested in drafting, landscape architecture, and material studies. He soon focused his sights on architecture, though his high school counselors and teachers advised him against it, saying that white people wouldn’t hire a black architect, and black people wouldn’t be able to afford him.

As an individual of pure determination, this advice undoubtedly fueled Williams’s resolve, and he categorically concluded that he would realize his ambition of becoming an architect. Williams went on to study at the Los Angeles School of Art and Design, the Los Angeles branch of the New York Beaux-Arts Institute of Design, and the University of Southern California, where he studied architectural engineering. In 1921, Williams became the first licensed African American architect west of the Mississippi; in 1923 he became the first African American member of the American Institute of Architects; and in 1957 he became the first African American to be inducted into the AIA College of Fellows. In 2017, 37 years after his death, he received the AIA Gold Medal, the institute’s highest award.

It is estimated today that only 2% of U.S. architects are African American. In 1921, when Williams became licensed, this figure would have been 0.04%. In the white, male-dominated profession of architecture, Williams faced racial and societal obstacles throughout his entire career, and though each of them could have been fatal professional hurdles, Williams saw an opportunity and upped his game. Step by step he outsmarted, outworked, and outmaneuvered his competition, and of his myriad talents, three of his strategies strike us as particularly remarkable.

1. While most of his contemporaries would deliver drawings within a few weeks, after meeting with potential clients Williams would promptly deliver carefully considered designs and drawings the very next day. He accomplished this by working all night, forgoing sleep, and skipping meals. It took a move as bold as this to demonstrate that he was unequivocally the best architect for the job.

2. Many of his white clients had never interacted with a black professional prior to engaging Williams, and as such, some of them were uncomfortable sitting next to him. To work around this discomfort, Williams taught himself to draw upside down so he could sit across the table from these individuals and deftly illustrate his ideas.

3. Unlike many of his white, male counterparts, Williams didn’t have the liberty to promote a particular design philosophy or aesthetic. Instead, to win commissions and complete projects, he became a master at many design philosophies and aesthetics; his projects ranged from the classical and traditional, to contemporary, utilitarian, and the design-forward. To be sure, mastering each of these ideologies is on par with learning a different spoken language.

[Williams Residence, photo via KCET]

It is truly staggering what Paul Revere Williams was forced to confront, navigate and master in order to become a successful architect. He gave up sleep and sustenance to beat the deadlines of his competitors by weeks; he trained himself to draw upside down to ease the discomfort of his white clients; and he learned to speak a multitude of intricate design languages to make himself versatile and nimble. All while tolerating glaring racial inequities, such as when he designed luxury homes in neighborhoods that commonly adopted rules that excluded African Americans from living in them.

[Palm Springs Tennis Club, photo via PBSSOCAL]

He pushed through all of this to become a prominent (and eventually celebrated) architect, and to uphold and advance a belief that everyone deserves good design. In addition to some of his more high-profile projects — such as additions to the Beverly Hills Hotel and the Palm Springs Tennis Club — he designed courthouses, churches and middle-class homes, which he charged a mere $10 per floor plan for. His belief that everyone should have a decent place to live led him to dedicate a significant portion of his career to affordable housing and pro-bono assignments. Of his most prominent public housing projects is Pueblo del Rio, which democratized affordable housing and brought together people from all walks of life.

[Pueblo del Rio, photo via Paul R Williams Project]

Williams was known for his strong personal connections—even some high school friendships became invaluable relationships later in his career. He yearned to make concrete improvements in the daily lives of people, be they famous individuals or common folk, and it’s clear from collaborative projects, such as the Theme Building at LAX, that he enjoyed the process of working with others. Paul Revere Williams died in 1980 and left a legacy that is being discovered and cherished to this day.

[The Theme Building at LAX, photo via Architectural Digest]

Thanks for reading and stay tuned for more.

-your friends at BUILD

Much more can be learned at the Paul Williams Project, which includes years of documentation by photographer Janna Ireland, and benefits from the persistence of the architect Phil Freelon, who worked to bring Paul Revere Williams to prominence.

RESEARCH CITATIONS

Wikipedia, NPR, 99% Invisible, PBS, Paul R. Williams Project