In autumn 2018, BUILD sat down with Ed Weinstein of Seattle based Weinstein A+U to discuss the prefabricated, modular Papali Wailea project he designed and co-developed on Maui in 2008. We discussed his design approach for the tropics, working within Hawaiian culture, and the wisdom of traditional island design. Read part 1 of the interview at ARCADE.

How did the driving ideas of a modular, prefabricated system translate down to the details?

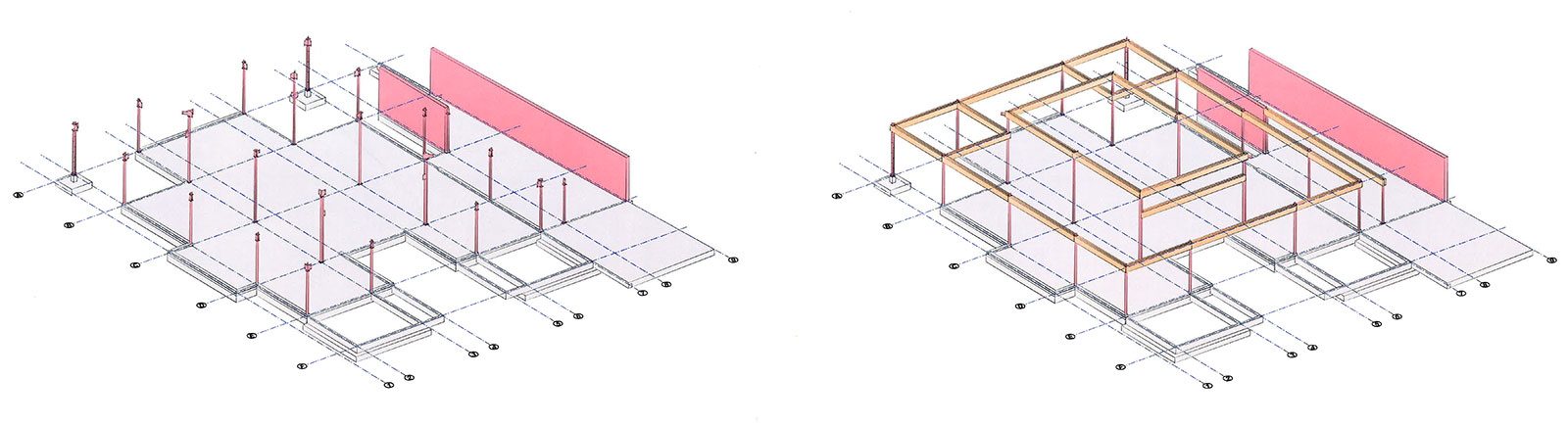

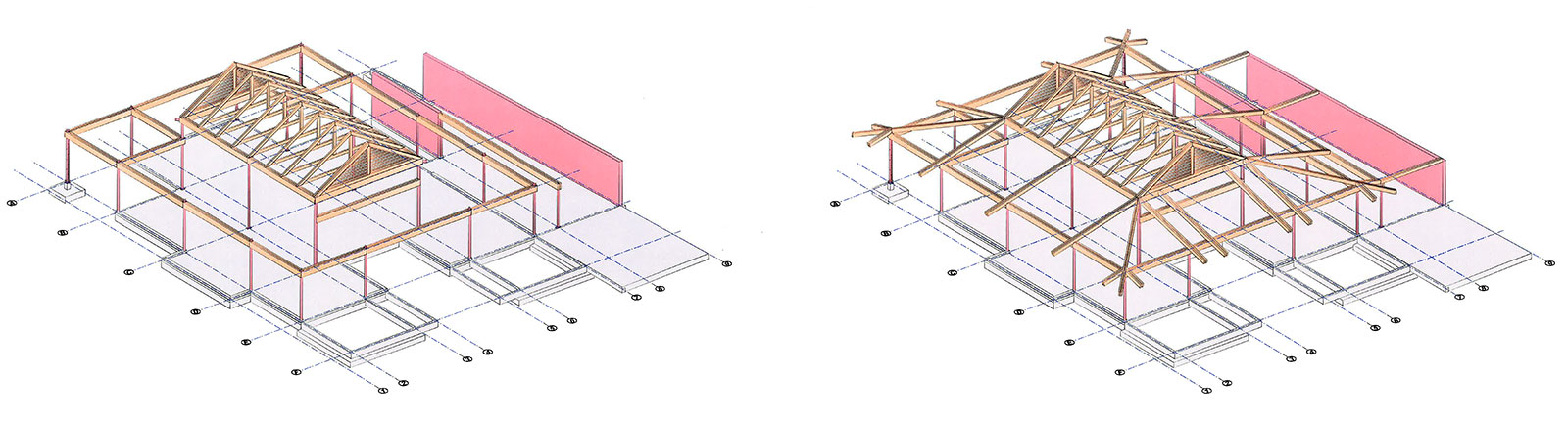

In desperation, thinking that we would lose purchasers, I conceived of this notion of prefabrication that was unlike anything else I had ever seen, but was related to protype design. Columns with intelligent flanges and tabs were barcoded to their gridline intersections on the plan. Then precut, predrilled, and pre-dapped glulam beams, purlins, and trusses would all be bolted to each other and the columns. I had the fundamental belief that a bolted together system would provide sufficient latitude to frame these houses, as long as it could be accurate within about a quarter of an inch every twelve feet. The process would also allow all the parts and pieces to be manufactured in the Pacific Northwest, and then shipped over in containers on a first in, last out basis. I understood relatively early that this was all a logistical exercise.

Did the quarter of an inch margin give the construction crews enough fudge room?

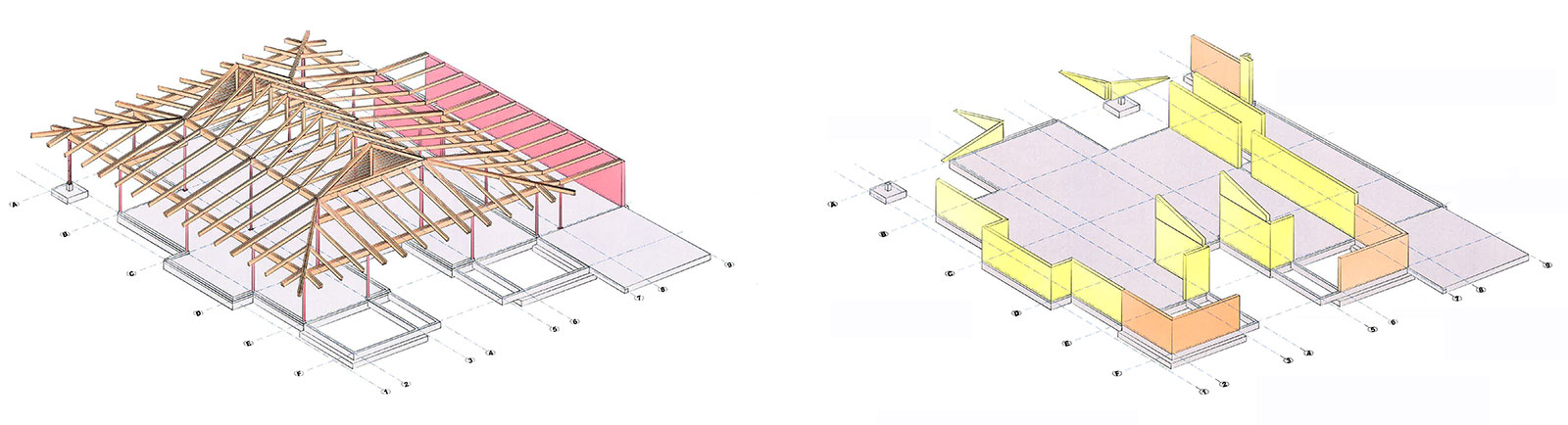

The key to the whole endeavor was being able to form and pour the essential slab, under which all of the infrastructure was located. The construction crew had no problem with pouring the slab and locating the gridlines, as the building pads were dead flat. Once the forms were stripped, we came back in with survey equipment to locate the grid lines; holes were then drilled, and the hardware was epoxied into place. Beams were connected to columns with the bolts loosely tightened and we had slightly oversized holes in the glulam beams to allow for a bit of inaccuracy. The frames were squared and plumbed with come-alongs on all sides, and the nuts were tightened down. Then the sheathing was installed at the shear walls and the purlins and trusses were installed. This was the protocol that we followed with each of the structures. Everything went together very quickly and very accurately.

How was the project sited to offer a view to each residence while maintaining privacy?

It was a proposition of working both ends against the middle. What I mean by that is that I started with a preconception of two single-family houses attached to each other at the garage common line so that these were really duplexes. I tried to get the prototype to be as small as possible and predicated on a four-foot module which was going to be the beam module. All window and cabinet systems would also fit into this module. Pairs of glulam beams with an air space in the middle created an 8” dimension, and the walls below flushed out to this dimension. At the macro level, there were imperatives about the site gradient, which required street slopes to allow access to fire trucks. It was an exercise of working three or four parameters against one another. The Wailea Design Commission was reluctant to agree that it should be an emphatic grid, so I tweaked the plan to be a slight arc and discovered that all of the houses could be aimed at the Island of Lanai.

What design assumptions did you feel compelled to interrogate in order to produce a successful project like this?

I was searching for a topography that stepped down so that every house could have a view. I was approaching that from the point of view of marketing and selling the product. So, I wanted to create a condominium community of single-family houses that were small in footprint but lived a lot larger via the inclusion of lanais, terraces, and courtyards. People could live in a community but have the privacy of a single-family house. I was looking for a slope that may not have been appealing to most builders because it wouldn’t accommodate the large footprints of condominium buildings. I convinced the owner to sell it to us with the condition that we would build at a low density and not obstruct views from surrounding properties. In order to be able to make it pencil out, we had to demonstrate that these houses could be sold at a premium because of their amenity and efficiency. I came up with the mantra “small houses that live large” as these structures have all the advantages of a single-family house with the benefits of a lock-and-leave lifestyle condominium with an onsite manager.

What are the hurdles for a mainland architect to get a project of this scale permitted and built in Hawaii?

The entitlement can be challenging. We were able to find a local planning consultant who had personal relationships with the planning staff, commission, and city council and could represent us as good guys. Other consultants helped us with the water and other infrastructure. There’s no way that an off-island developer could possibly be successful without local representation.

The marketing was the second hurdle. A marketing firm helped us understand what the product should be and the valuations of that product. They also helped shape the story of this project so that it would resonate with buyers. Since it’s not a waterfront property, we had to craft a story about the views from the property, and all of the amenities such as the covered lanais, the fitness center, and the pool. We needed a host of alternative strategies to make up for the lack of waterfront.

The third challenge was discovering and appropriating methods of prefabrication tuned to the skill set on the island; after that is was just a matter of execution.

So much of this project had to be invented from scratch. Were there projects or experiences in your past that you could rely upon here to guide you through?

I have a great deal of experience with single-family houses, which was significant to the conceptualization of the individual units. The site plan also required an abundance of knowledge related to multi-family housing. It was pure invention with the prefabrication system because we’ve never had the need to do it here in Seattle. It was sheer speculation.

Did the location and environment require you to think differently as an architect?

Absolutely! And I have to acknowledge my initial ignorance of the roof form, which had nothing to do with the site or the climate. My preliminary conception of these houses was of modernist pavilions with butterfly roofs; but in my first meeting with the Wailea Design Commission they said this was too aggressive and modern, and that there is a tradition of hip and gable roof forms on the island. They would approve the site plan, but they wanted us to think about a different roof form. So, I rethought the project as a hip-gable roof that had lower eaves with extended overhangs, and operable hopper windows in the gable for natural ventilation. This is a time-honored roof form in tropical climates because it gathers the heat high in the roof peak and expels it through the vents at the gables. It worked beautifully.

Ed Weinstein has practiced architecture in Seattle for 48 years and is the principal and founder of Weinstein A+U. He obtained a Bachelor of Architecture from the University of Washington in 1971, and a master of architecture from Harvard University in 1975. His award-winning projects include housing, institutional, public sector, and commercial work. Ed has been a graduate studio instructor, has mentored many generations of young architects, and has made significant contributions to Seattle’s architectural legacy.