[Steven Holl and Ed Weinstein, photo by Andrew van Leeuwen]

Last summer, BUILD sat down with Steven Holl and Ed Weinstein in Seattle’s Pike Place Market to discuss their humble beginnings, their common educational paths, and the life experiences that produced two distinctively successful architecture practices. Part 1 of the interview can be read here.

You’ve both been described as individuals who completely dedicated themselves to the practice of architecture. What has this entailed in your own lives?

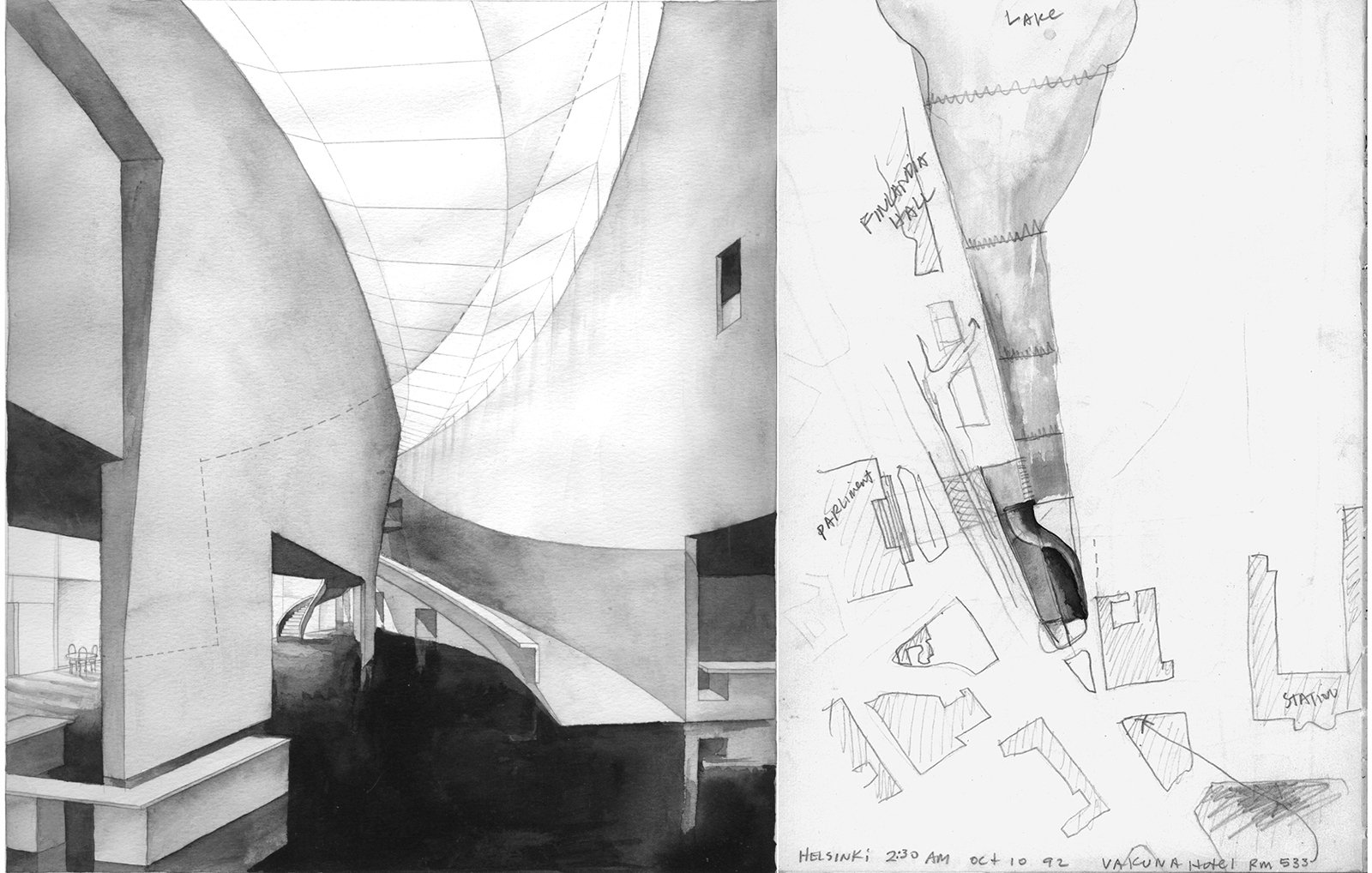

Steven Holl: I think for me, architecture was the right thing to do. It’s something you believe in. I never had a doubt. I wasn’t going to do commercial work, but there were doubts I could survive and that’s why teaching was important. Then my firm won some competitions, like the Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art in Helsinki in 1993, which saved me. I was losing my office and hadn’t paid rent in six months. We won the competition and survived. Architecture is great art and a terrible business.

Ed Weinstein: My take is similar but from a different lens; a lens of Seattle and the Northwest instead of international. I’m always humbled by what I believe is my ability to know good and great architecture but not always being able to achieve it. I think it’s important to stay hungry and humble. I feel like when we were younger, we had this vision of what architecture could be for our lives and it was so important that I was always fearful of compromising and embarrassing myself. It’s such a noble thing to do the very best you could — even if every day you couldn’t consistently achieve that. Steve did it with competitions, teaching, the willingness to be penniless at times, and being way out over his skis. I was in the same situation, while being a little more stable with a marriage and a family. If you elect to achieve architecture with a variety of building types — whether they’re institutional, public, for-profit development, whatever it is — there are all these compromises that are presented to you every day. We’re still dealing with the residue of the recession. Yeah, it’s a terrible business, but I’m pathologically ill-equipped to do anything else. My world view is that of an architect. The shaping of the environment and leaving a legacy of good buildings is very important to me.

[Watercolors of Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art by Steven Holl Architects, photo courtesy of SHA]

Are there certain characteristics you see in designers that go on to succeed as opposed to those who become discouraged? What’s missing from their toolkits?

SH: It’s enthusiasm for what space, light, and geometry are. If you go to architecture school, it doesn’t mean you have to become an architect and have a practice. It’s an urge, a dedication. It comes out of the work. It’s not about a tool, if you don’t have the passion. It’s not like you can turn it on or off. Architecture surrounds you. Paintings, you can turn away from. Out of my 12 students, I don’t think they’re all going to become architects. I don’t think that’s a tragedy. Learning about architecture is a good education. It doesn’t mean everybody has to make a business out of it.

EW: In graduate school at Harvard, Jerzy Soltan told us that there were no great American architects. He said none of them were poets. In the early 70’s, he was very dismissive of Kahn specifically. A colleague of mine had a copy of an article from the Pennsylvania Gazette, which was an interview with Louis Kahn that was called “How am I doing, Corbu?” Kahn, who you would have thought at the time was a very confident architect, writes about everything he does as an offering to architecture. In the interview, he said, “When I’m quietly working in my office in the evening by myself, and no one’s around, I am oftentimes wondering what Le Corbusier would say about my sketches if he were standing over my shoulder.” He took it to Soltan and said, “What do you think about Louis Kahn now?” He came back very much humbled by it. It was such a charming thing because Kahn was always wondering how others might view his work, and it kept him humble. For me, it’s the humility of knowing you could always do better work.

[Fire Station 10 by Weinstein A+U, photo by Michael Burns]

How does the size of a project influence the experience of designing it?

SH: I still love to do houses. Architecture doesn’t need to be big to be meaningful.

EW: On the smaller projects, you need to focus at the detail level. An architect or small team can achieve closure on a smaller project in a way that you can’t on a bigger one. I still get incredible pleasure out of a small project or even a retail store or something like that because you’re focusing on a limited set of issues and you have more control over them. The thing you feel at the municipal level, is that there are so many actors that can influence the outcome. You have to have a strong concept and willingness to be really tenacious in protecting that concept to get a design realized.

SH: We just did a 970-square foot house in Rhinebeck, the Ex of In House. It was such a pleasure just to do that project and build it in 11 months. I have four buildings opening this year and that’s exciting but some of them I’ve been working on for 10 years. When you’re working on a house, you can have a very complete experience in a short amount of time.

[Ex of In House by Steven Holl Architects, photo by Iwan Baan]

The professional design environment as well as the US Census Bureau both suggest that small and medium sized firms are dwindling (barely keeping up with population growth), while large firms continue to grow aggressively. As practitioners that started small and continue to run medium sized architecture practices, what advice do you have for architects wanting to hang their shingle?

SH: It’s the nastiness of the business world. It’s not unusual for corporate offices in New York to employ over 300 people. The way it works is that they’re in groups and they have 10 partners who lead sub-studios. It’s just like a machine, cranking out work. There’s not much time spent on design because they make a profit on every building. Being 300 strong, you can have a total machine that gets the work. The small office can hardly afford to keep the staff to do the work. You don’t have the money to go out and build the machine to suck up the work like a vacuum. They can find out about the work through the grapevine, and the big firm will already be there with a proposal and a rendering. I blame the situation on the lack of architectural education on the part of the clients. If they had a little more desire for quality, they wouldn’t just give it to this corporate world. Kahn says, “Architecture does not exist, what exists is the spirit of architecture.” There is a lot of building construction, which is a measure of economic growth. My office is across the street from Hudson Yards and it’s just big reflective glass. It is so banal. It is a measure of real estate. Down the road is Neil Denari’s little condominium on the high line. That’s a work of architecture. It’s like night and day. Architecture is an art. Neil treats it like an art.

EW: I think when you started your firm, it wasn’t a conscious decision. You were doing competitions, you were expressing yourself and you backed into having a firm because it was what you needed. I probably did the same thing. There was never a conscious decision on my part to start an architecture firm. The only reason to have ever left a comfortable job with a steady salary, where someone else was bringing in the work, is the chance to have total control: to fail or succeed on your own terms, without someone getting in the way. I think for many of us who started our own firms, it was solely that you wanted to express yourself and see if you could succeed. I can’t imagine starting a small firm as a rational business proposition. I had high ambitions and I wasn’t willing to stop designing because we were out of money or we hit a deadline. If it meant working all night for two or three nights to get where we wanted to go, so be it. That’s part of the equation. I think those circumstances still exist. If younger architects are still motivated to do that, then they have no other possible avenue. They need to think it through, because as Steven indicates, you have to be a jack of all trades when you start your own firm. You have no idea about the complexity of securing work. It has to be under the right circumstances with the right set of values or it is just a path to oblivion. Finding the clients that will allow you to do what you need to do is the hard part. When you see a young firm succeeding, you take off your hat and say more power to you. Go for it. In that context, I am overwhelmed by the Danish firm, BIG.

SH: If the AIA were to do something for architecture, they would set a limit to the size of architecture firms. The same as they do for monopolies that try to take over in our business culture; we’ve got to set a limit. I would say the limit is 44 people. That is a maximum size architecture firm that you can have. By the way, it doesn’t take that many people to do a skyscraper. I can do a skyscraper with six people. You don’t need 300 people. That is just greedy.

[Museum of Fine Art Houston by Steven Holl Architects, photo courtesy of SHA]

Inventing new concepts in architecture requires an enormous amount of trust from a client. How do you enroll clients to go on the adventure with you?

SH: A lot of our work comes from competitions, so our test becomes when you present the scheme. When we presented the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, we were up against Snohetta and Thom Mayne. I said we felt strongly that you shouldn’t build a seven-story parking lot. They had an existing school and they had to build a parking garage in order to build this new building. I said, “You should not build this, because you could never expand your school. Instead, you should build a new school, put the parking below, and now you can have a sculpture garden that’s twice as big. It will be bigger than Dallas.” At the end of my presentation I said, “I know you may not have been thinking of this as the path, but the buildings can work very well together, and this is a very important decision. This expands your campus for the future. Also in the competition for the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City we had to break the rules to do the more ideal scheme.” I said to the jury, “You know how I got the courage to break the rules? Carved into the façade of the Wight building from 1933, it says ‘The soul has more need for the ideal than the real.'” I had the courage to make the ideal scheme. At the end of my presentation they had a unanimous vote for my project.

EW: I think it’s inevitable that architects get themselves into situations where if they’re motivated by a concept that they think is appropriate and circumstantial, and that they really believe in, then they need to defend it. If they’re asked to compromise, it becomes an existential challenge.

SH: You need the person that’s got the power to make the decision there. You’ve got to present it one on one. In the case of the Sliced Porosity Block in Chengdu, China, that we designed, they were going around and they had something like 200 projects in China. They hired us to do a scheme. What they usually do is build an office tower and a condominium on top of a shopping center. What I wanted to do was to put everything around it; make a big public plaza, three levels, and cut it to the sunlight. I made a set of drawings, a set of little models, and the director came through and he said, “It’s brilliant, go for it.” It was a huge company, but he was the head of the company and he made the decision.

EW: The scale of our issues is different. It’s inevitable. I know some of my clients through the years have felt that I’m hard headed and argumentative, and that’s probably true, but being argumentative for the right reasons is laudable and should be done. I’ve had staff who say, “why do you care so much?” and I just say I’m fearful of embarrassing myself, I know that this could be better. If we compromise here, we’re going to compromise there the next time, and I can’t live with that outcome. I’ve had to explain that to clients and say, “If you like the outcomes that you’ve been getting with us in terms of thorough documentation, constructability, and enthusiastic and expedient approvals from Design Review boards, then you should want us to care about everything, you can’t pick and choose. If you care, you’re going to get pushback at times.” I don’t know how to practice other than that.

[Fire Station 22, photo by Kelly Rodriguez]

What characteristics differentiate your separate practices?

EW: When we push the envelope, it’s maybe in a different way than Steven would do it. I think he’s made pretty significant contributions to architecture through his investigations into typology and phenomenology. There is a really consistent set of investigations that have been important to architecture because of the publication of the work and his lecturing. Ours, I hope, are thoughtful contributions that will inspire architects here in Seattle to get the most out of their circumstances. I’m intrigued by the outcome of a little building that we’re doing up on Roanoke Street, Fire Station 22. The building was designed backwards. The site mandated that everything that would have been back of house is foreground. The apparatus bay had to be on the non-public side. The design commission was very ill-at-ease with such an abstract building. We said the only way to do this was with a really strong concept. It is almost complete and I think it will realize our ambitions.

Given that you’re both architects of many influences, what else do you recommend that architects or architecture students get exposure to?

EW: First moves should be from some conceptual basis that is not immediately apparent and takes a great deal of thought and analysis to get there. We’re always looking for authenticity of architecture. It cannot be imposed and it cannot be stylistic. From my frame of reference, it has to be predicated on the simultaneous analysis of site and program: phenomenology of site and the dynamics of our society. I think it was Herman Pundt who said, “A building must be more when you go in it than when you look at it.” No one is paying attention to the present moment. There is so much available to us visually without any meaning that I am concerned that we will be losing meaning in architecture because it is so easy. Le Corbusier’s biography was titled Creation is a Patient Search.

SH: I loved my art classes: painting, making things, hanging out at cafe Parnassus in Seattle. I, too, loved the teachings of Herman Pundt while at the University of Washington and I hadn’t met Astra Zarina yet. I hated several other professors to the point that I was going to drop out of architecture. I had this teacher and he said, “I wouldn’t do that if I were you. I used to be an architecture student and I dropped out and now I’m just an art teacher.” He gave me a C in art that term, and that totally discouraged me from dropping out of the architecture school.

With Ed having raised two children and Steven just beginning the journey into fatherhood, what wisdom about your careers do you hope to pass down to your children?

EW: What is interesting for me is that my older daughter went into architecture school. All of her youth she wanted to be an actor. After undergraduate school, she applied to the University of Washington for graduate school in architecture and was accepted. I never thought in my wildest imagination that my daughter would become an architect. In order to be able to be engaged in their lives I’d had an office at home. We had children — what I thought was late. The greatest part of supporting them fell to my wife, but I needed to be there evenings and weekends. When they went to bed at night, I could go to my office and work. On the weekends, I could get up early, work, and go to soccer practice. They would take a nap, and I would work more. I’m sure their sense of me is looking into my office, thinking “that’s what a dad does.” I guess it was subliminal for my older daughter, Laura, to consider architecture. She eventually developed an auto-immune disease and realized she didn’t have the stamina to become an architect. She’s used it in a positive way, which is to be a family counselor and art therapist. In a curious way, I think my life as an architect has had an influence on her career choice and certainly how she views the world. My younger daughter wanted to be in the film industry and went to LA and worked for a few years in the talent management industry. Now, she’s working in corporate communications for Starbucks. She is naturally a very outgoing personality, she loves the corporation, and it’s a great place for her. I think on the whole, both of them feel that they have benefitted from the fact that their father was an architect. It’s just in their world view and sensitivity to urban issues and the environment. I guess I could have made more money and they could have had a better financial platform, but it was not the end of the world.

SH: When people asked, “do you have any children,” I would say, “No, my buildings are my children.” I haven’t done that many. I always go back and visit them; check on them and see how they are doing over the years. I always go back to St. Ignatius or Helsinki or the Bellevue Art Museum. It’s kind of a surprise now that I actually cannot say that anymore.

EW: If I may say something — I am absolutely charmed by his response to his daughter, which is everything you would expect a father should be. It’s even sweeter that it comes later in life. It is a wonderful outcome.

SH: She’s got a lot of confidence. Zaha Hadid visited and gave her an Issey Miyake, but I think Zaha gave her something else in addition, like this kind of confidence.

Is there a particular book you consider required reading for architects and architecture students?

SH: My own book, Questions of Perception, republished in 1993, through William Stout architecture books. Also Anchoring, which came out of Princeton Architecture Press, and argues that every building has the unique site and circumstance on situation and culture. It shouldn’t be about carrying on a signature from one site to another, it should be about building to the site. I did a book called Urbanisms which argues for hybrid buildings, which are ingredients of the city with a mixture of living, working, cultural, and recreational components. Buildings like that need other ideas to inform them. They’re not about an office building program; they’re not about an apartment building program. It is an argument about urban design. There’s another book called Hybrid Buildings that came out of A+T. Peter Miller’s bookstore here in Seattle has quite the collection of books on theory and books on contemplating about architecture. He’s the place to go for recommendations.

EW: A book I got early in my career was a little black pamphlet called Louis Kahn, Teachings at Rice. There’s so much in that little pamphlet, even just about thinking through a problem. I will never forget the one part of it where he was designing a seminary in his studio and they invited a monk to come in and critique it. All of the students had distributed cells in the landscape, and the monks had to walk outdoors through the woods to get to the common facilities. Kahn said, “I was encouraging this, as a contemplative path,” but the monk said, “What? I’m going to get wet; its cold; I want to be right next door.” I thought it was brilliant for the presumptions on the part of the students and Kahn himself that there was something they imagined would supersede the practical requirements of the monk.

[Steven Holl, Ed Weinstein, John Ullman; photo courtesy of Ed Weinstein]

Steven Holl established Steven Holl Architects in New York City in 1977. He obtained a bachelor of architecture from the University of Washington in 1970 and completed his post graduate studies at the Architectural Association in London in 1976. Steven is considered one of America’s most important architects and has completed cultural, civic, academic, and residential projects both in the United States and internationally. Steven is a tenured Professor at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture and Planning, has lectured and exhibited widely, and has published numerous texts.

Ed Weinstein has practiced architecture in Seattle for 45 years and is the principal and founder of Weinstein A+U. He obtained a bachelor of architecture from the University of Washington in 1971 and a master of architecture from Harvard University in 1975. His award-winning projects include housing, institutional, public sector, and commercial work. Ed has been a graduate studio instructor, has mentored many generations of young architects, and has made significant contributions to Seattle’s architectural legacy.