[Image via MAKcenter]

In the shadows of the most celebrated houses of the 20th century are a wealth of projects every bit as important as the known icons of residential design. Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye, Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion, and projects of equal fame in the design world have their rightful place on the cover of glossy design books and at the top of every architecture professor’s syllabus, but these projects do not embody all the necessary teachings of the design world. In fact, some important architectural lessons go entirely overlooked simply because of their celebrity.

Beyond the sensationalism and the glamour, there resides a tier of houses that is lesser known and a bit grittier, with projects that offer some of the most profound lessons in design. Some were designed early on in the careers of famous architects and contain the seeds of experimentation that would later play out in houses of greater fame. Some projects were the work of architects that, despite their significant contributions to the design world, never became household names. Others, still, were projects ahead of their time to such a degree, that it took society a lifetime to appreciate their impact.

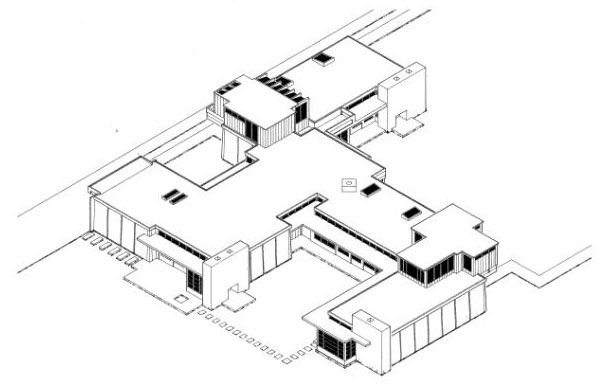

Schindler-Chase House in West Hollywood by Rudolf Schindler, 1922

Pushing both an architectural and social agenda, the Schindler-Chase house was a significant departure from residential design precisely for what it didn’t have. Conceived as a cooperative live-work space for two families, the interiors use an open and flexible floor plan rather than designating functions per room. Bedrooms are replaced with sleeping lofts and common areas keep the total area to 3,500 square feet. Also of particular note are the concrete walls which were poured atop the slab on grade and tilted into place. Glass panes fill the slender gaps between panels adding a rhythm to the exterior massing walls. The sturdy concrete partitions allow the wood window walls to appear light and lace-like.

[Image via MAKcenter]

[Image via Wikipedia]

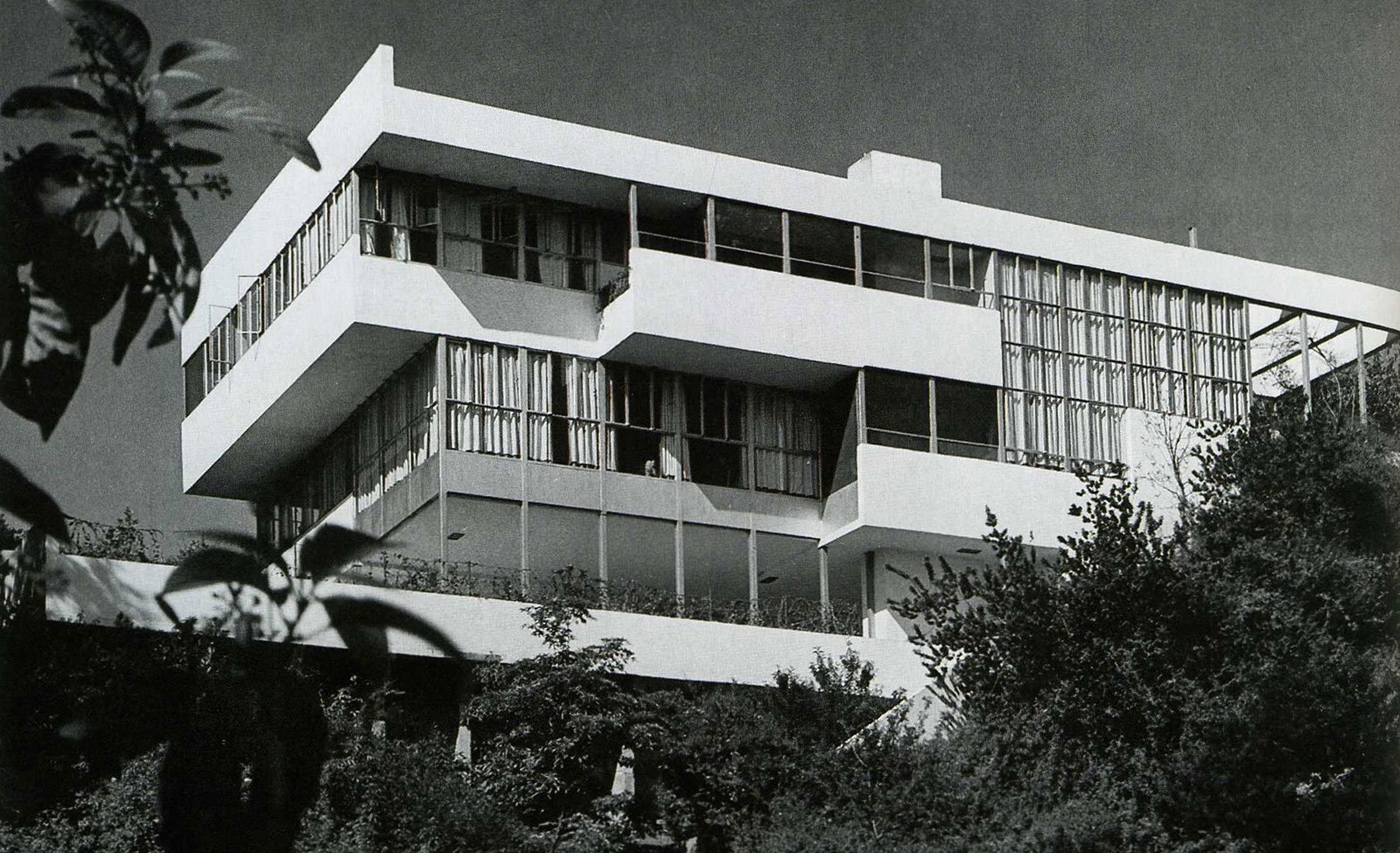

Lovell Health House in Los Angeles by Richard Neutra, 1929

Using design-forward materials and methods, the Lovell Health House incorporated steel frames, a light-weight synthetic skin, double-height glass walls and the use of gunite, a technique for spraying concrete on a vertical surface. Borrowing many of these elements from commercial buildings, the project became an important example of the international style. In addition to its technical qualities, the project was also well ahead of its time sociologically as the design concept investigated the benefits to physical and mental well-being through thoughtful, unencumbered design.

[Images via archdaily]

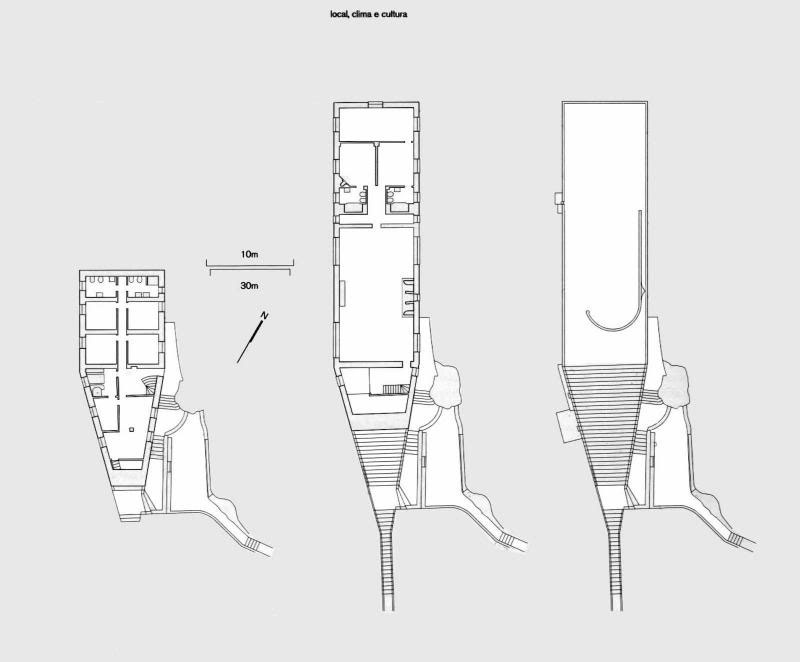

Studio of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Mexico City by Juan O’Gorman, 1932

One of the first examples of functionalist architecture in Mexico, the separate but adjoining volumes house living quarters and artist studios. Designed as a factory for living and making art, the unapologetic architecture is the analytical result of the activities that took place inside and a representation of the precarious relationship of its inhabitants. Both structures are raised on stilts to allow a free-flowing garden to occupy the ground plane below. As a response to the housing challenges of Mexico City, the project used common materials and was constructed for a minimal cost.

[Image via Wikimedia]

[Image via Estudio Diego Rivera]

La Maison de Verre in Paris by Pierre Chareau, 1932

The stunning visuals of La Maison de Verre owe credit to an industrial palette made of glass block, steel beams and exposed bolts. The translucent wall of the double-height salon takes on the quality of an elegant shoji screen while the connection points of the steel columns become a design feature with their distinct red highlight. Interior spaces are created to be flexible and adaptable by means of sliding, folding and rotating panels, while mechanical components serve as overhead trolleys and retracting stairs. Most notably, and least visible, is the project’s clever insertion under the 4th floor flat of an elderly owner who refused to sell. The project was a design-forward vision not only of architecture but also of the tenacity and rigor required of the design profession.

[Images via yellowtrace]

Casa Malpartre on Capri by Adalberto Libera, 1937

Nestled on a dangerous cliff off the east coast of Capri, Casa Malpartre appears more as an object discovered by chipping away at the rock walls than one placed atop its site. The interior spaces and roof terrace each take their programmatic cues from the jagged terrain as the surrounding vegetation veils the structure’s elevation. Conceived as a place for solitary contemplation and writing, the structure embodies both a humility and purity of form rarely seen in modern architecture.

[Images via The Gilded Owl]

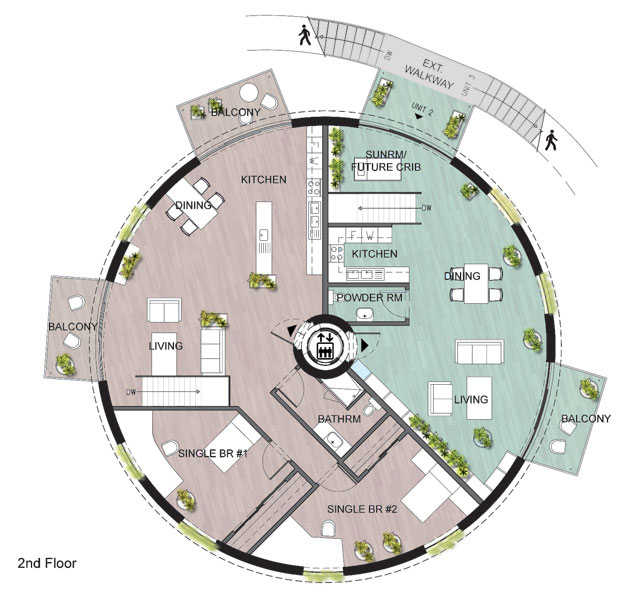

Dymaxion House by Buckminster Fuller, 1945

The quintessential engineer, Buckminster Fuller charged himself with solving the problem of affordable, mass-produced housing that was easily transportable. The Dymaxion House was his answer and stood for DYnamic, MAXimum, tensION, as the structure used tension chords attached to a central column, circulating out to form a well-organized round plan. It is said that the house sold for the price of a Cadillac and could be shipped worldwide in its own metal tube, thereby economically answering the housing supply crisis of post-World War II America. The concept never gained popularity, perhaps because of its disregard for the nostalgia of the American single family cottage or its disconnect from local site conditions. Nonetheless, no one has provided a more efficient model for the mass-produced single family dwelling.

[Images via Garden Home]

Casa Barragán in Mexico City by Luis Barragán, 1948

Confronting the visitor as more fortification than dwelling, the austere street front of the residence cleverly blends with its banal surroundings. Once inside, the walls become colorful backdrops to airy rooms and lush gardens. The use of crisp, bold forms creates a peacefulness to the spaces, while texture replaces ornament. Drawing inspiration from peasant quarters and stables, Casa Barragán took minimalism a step further to the abstraction of form.

[Image via Wikiwand]

[Image via ArchiTravel]

Liljestrand House near Honolulu by Vladimir Ossipoff, 1952

Practical and serene, the Liljestrand House embodies the poetic restraint of mid-century modern design. The roof framing is left exposed, creating a harmony between aesthetic and structure. Floor to ceiling windows maximize natural light and allow the views and surrounding nature to become an important ingredient of the architecture. Even the positioning of the house uses the natural weather patterns to properly cool the interiors. The Liljestrand House remains an exceptionally thoughtful example of environmental and lifestyle design.

[Image via Archinect]

[Image by BUILD LLC]

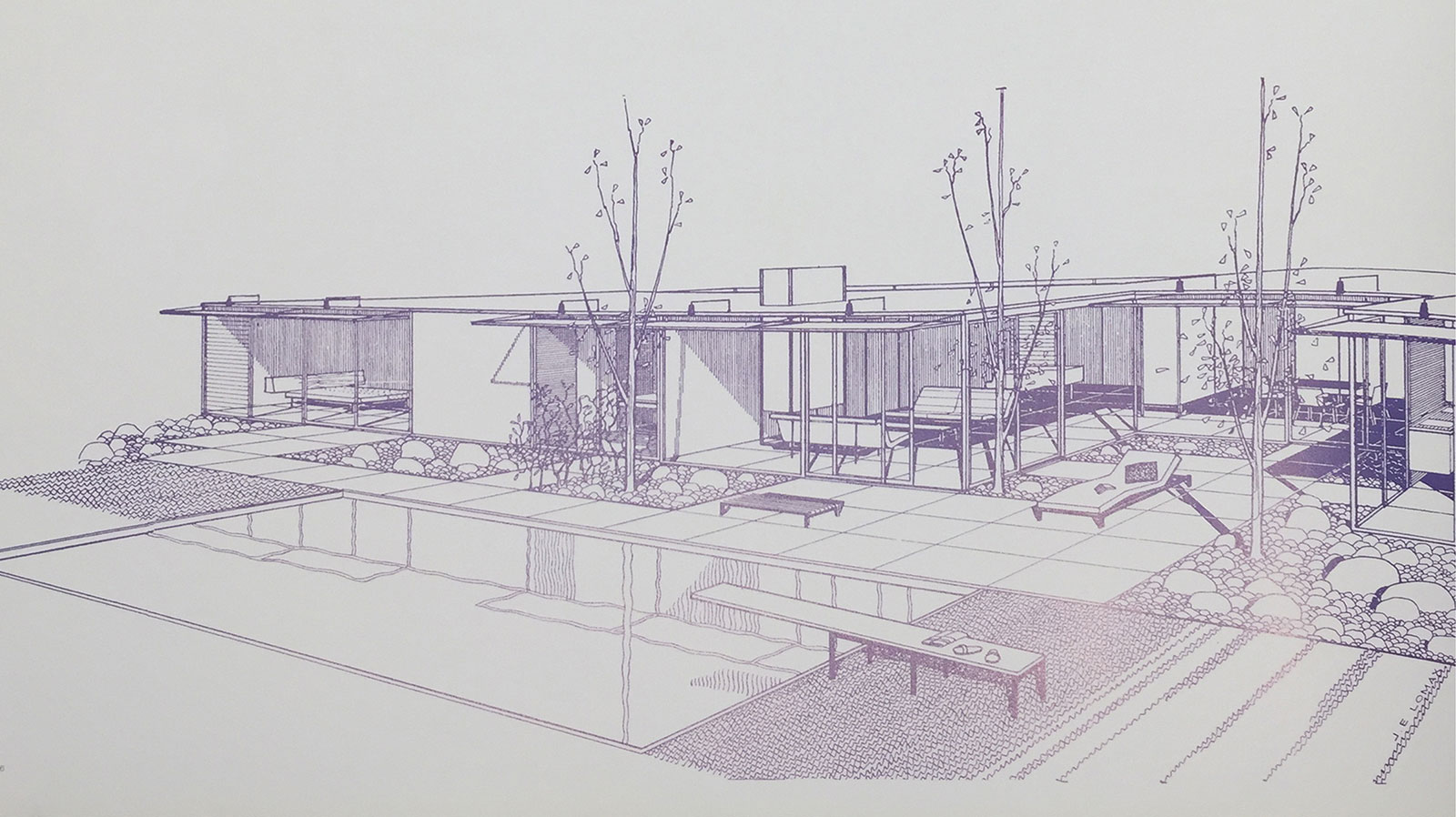

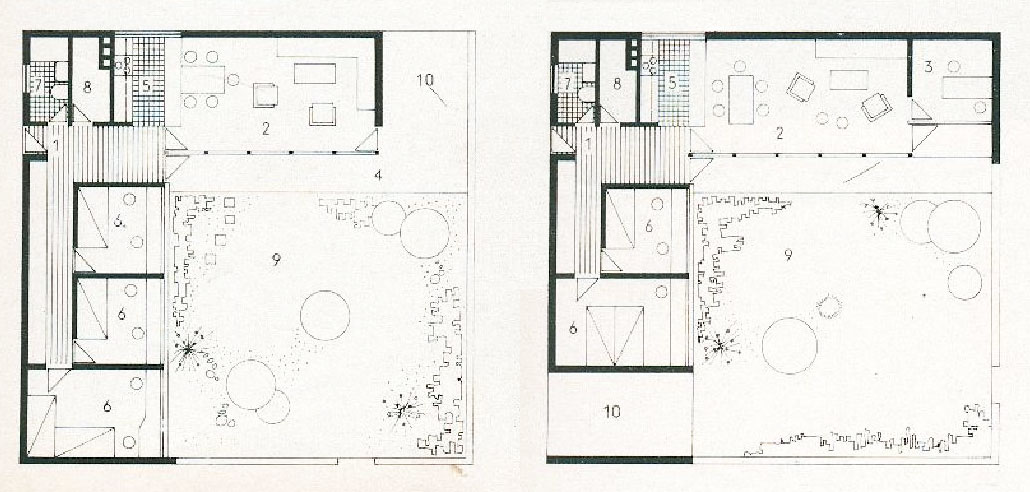

Case Study House #18 by Craig Ellwood, 1958

One of the most rational architects involved in the Case Study House program, Ellwood’s training as an engineer was particularly well-suited to adapt an industrial kit of parts to residential production. Focusing on standardization and repetitive steel frames, CSH#18 creates a machined sensuality and establishes that plain can be elegant. The project also developed the use of screen walls to both provide privacy and complete the exterior architectural composition.

[Images via Case Study Houses]

Maison Carré in France by Aalvar Aalto, 1960

Pushing modernism to the next level and breaking from the purist box, the Maison Carré brought visual warmth and new geometries to the modernist vocabulary. In a bold architectural move, the roof structure builds from a single and ascending angle, creating a collection of dramatic shed roofs. Incorporating texture into the envelope, masonry is used at the exterior walls but the brick is painted white to keep with a design-forward color palette. Inside, as a departure from the exterior geometry, a wood clad wave is introduced to calm the space and gently guide visitors to the common areas. Designed as a residence for the display of art, specific considerations for natural light and indirect light create an elevated quality to the interiors.

[Image via afasiaarchzine]

[Image via afasiaarchzine]

[Image via archdaily]

Frey House II in Palm Springs by Albert Frey, 1964

While this compact, 800 square foot home incorporates many exemplary characteristics of modernism, like steel frame construction, a simple shed roof, and window walls that visually disappear, the relationship to the landscape is what separates this dwelling from others of the era. From the approach, the structure modestly pokes its head up from a rocky landscape, expressing a humbleness seldom associated with modern architecture. A closer look reveals that the structure isn’t so much built on top of the landscape, but tucked within. As an act of respecting the site, a large boulder is incorporated into the plan which becomes part of the architecture and separates the bedroom from the living area. Similar moves create a strong contrast between the delicate modernism and the rugged landscape. The Frey House II established the profound relationship modernism could have with nature and the project played a significant role in creating a regional architecture.

[Image via Lumis Photography]

[Image via Lumis Photography]

[Image via yellowtrace]

Fredensborg Housing in Denmark by Jorn Utzon, 1965

Setting an example for future residential developments in Scandinavia, the Fredensborg Housing established 47 courtyard homes and 30 terraced houses within an urban fabric of community. Arranged around a series of courtyards, each home maintains its autonomy while opening to shared greenspace beyond. Each ‘L’ shaped dwelling benefits from ample southern natural light as the project steps down a sloped hillside. Community is further nurtured in the development with the inclusion of a central building containing a restaurant, meeting rooms, and guest rooms for visitors. The project continues to be the finest example for single-family community living.

[Image via Pinterest]

[Image by Ramblersen via Wikipedia]

[Image via Pinterest]

Most architects and design professionals will likely have a familiarity with these projects, as they tend to be covered at some point in an architectural education. For architects, this list may act as more of a re-acquaintance with some old friends. For the non-architects, we hope this list introduces a few new projects, sparks some fresh ideas, and adds a few houses to the list of favorites. When properly considered, these lesser known projects have actually been more influential to our design work here at BUILD than the more celebrated icons of architecture.

Cheers from Team BUILD