[Magnolia House + Guesthouse by BUILD LLC]

It’s been a while since we covered one of our favorite topics on the BUILD Blog: architectural photography. Years ago we started taking our own photos as an architecture firm, and once we learned the basics of capturing a good shot, there was no turning back. We had no idea back then how important that decision was for us. The advantages of taking our own photos and owning 100% of the image rights are significant, especially in today’s image-saturated, high resolution, digital age. This is also a momentous way to wrap up a completed project and step back to take in the full journey between original design intent and final product.

[Magnolia House + Guesthouse by BUILD LLC]

We’ve made significant upgrades to the BUILD camera kit since our last post on the subject (yes, kids, that would be CS3, the hottest software package on the block). And while our hardware updates have been measured and judicious, (equipment upgrades just don’t jump as high nor as quickly as software,) we continue to ride the light-speed trajectory of photography software. In short, the digital processing does most of the heavy lifting. And we’re also at a point where we’ve honed our photo shoots down to a precise science. It’s customized to our needs, (limited,) and our time, (very limited,) while utilizing some tried and true architectural photography methods. Today’s post shares it all along with a handful of valuable resources.

[Mercer Island Project by BUILD LLC]

Before we geek out on the gear, let’s cover a few reasons why it’s important for us to take our own finished shots and what we’re doing with them. While it’s important to get images of each completed project to be used in publications, websites, blogs, social media, and whatever comes next, these promotional shots only make up a fraction of the photos we capture. Many of the shots we take document the details and specific conditions of each project. Most of these shots never leave the office. Rather, they become reference tools to set the proper expectations with clients and accurately represent options within the design process. These photos can indicate details as minor as cabinet pull options and bathroom tile patterns or as significant as roof geometries and how a structure engages with the site. Whatever the scale, there are few substitutes that communicate as well as photos of previous projects.

[Mercer Island Project by BUILD LLC]

Given the documentary nature of many of the shots, the average project may result in 100+ finished images, and having a professional photographer provide a portfolio this extensive would result in a staggering invoice. To the pros credit, a top-notch photoshoot just takes a lot of time and expertise to schedule, coordinate, conduct, process, and deliver. But as a small firm, we’ve always needed a full range of shots without the hefty price tag. While giving up a day in the office doing architecture isn’t always convenient, the results of having a complete portfolio of each project are well worth the time and effort in the long-run.

[Magnolia House + Guesthouse by BUILD LLC]

Most of the consultants and trades that we work with are in the same boat, they simply don’t have the financial luxury to hire a professional photographer to thoroughly document each and every project. One of the benefits of working with the BUILD team is that we give our photos to anyone that works on our projects. It’s one of the ways we show our appreciation for their hard work and dedication. In addition to all of those reasons to shoot our own photos, it’s simply an enjoyable way to celebrate the completion of a project and honor the transition of a finished product from architects and builders to the owners.

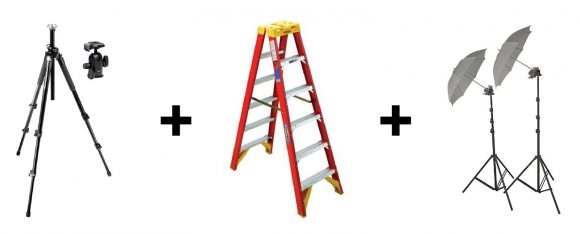

Now, onto geeking out on gear. We recently upgraded to a Nikon D610, which at about $1,500, is Nikon’s least expensive full-frame DSLR. While you can go crazy with the glass, we really only use two lenses in our work. The Nikon AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm f/2.8G wide angle lens ($2,000) captures the greatest amount of area without going to a fisheye lens, while the Nikon AF-S Nikkor 50mm f/1.4G ($450) is our go-to lens for lowlight conditions where we don’t have or can’t use a tripod. A tall tripod is absolutely essential for architectural photography, and we use the Manfrotto 055XPROB with 484RC2 ball head ($350) as it’s easy enough to pack around but tall enough to capture a wide range of shots. Perhaps most surprisingly is the importance of a 6’ ladder on architectural photoshoots — the additional height gained with a rudimentary household ladder has become fundamental on our photoshoots ($150). For interior shots we pack two Lowel Tota halogen lights with their necessary stands along with a couple of translucent and silver umbrellas ($375 for the pair). These help highlight darker interior spots and bring interior exposures closer to the level of the exterior exposures. While we don’t use flash photography much on our projects, it is handy to have a flash in the office for headshots and whatnot, and we’ve had success with the Nikon Speedlight SB-600 ($400). Throw in a bag and some additional accessories and the grand total of gear comes to about $5,500 before tax which, at the rate we take photos, paid for itself in two or three project shoots.

As steadily as camera equipment has advanced, the software to process photos has brought even greater horsepower to the semi-professional toolkit. We recently jumped on board the subscription based Adobe Creative Cloud which includes a host of programs, most notably Lightroom and Photoshop. Adobe Lightroom is a must for processing photos. While we could spend hours praising the abilities and tools of Lightroom, the number one benefit is its ability to process RAW image files. The RAW image format captures a greater spectrum of light and color compared to .jpgs or .tifs. Lightroom can then reclaim this broader spectrum and export .jpgs or .tifs that are better exposed and richer in color. This is most important for interior architectural photography that also captures portions of the exterior via windows or doorways. Typically, the darker interiors contrast with bright natural light outside and a proper exposure of the full spectrum of light is challenging. If processed correctly, the RAW file format can collect the lights, darks, and everything in between. We use Lightroom for a variety of other adjustments such as temperature, clarity, saturation, color balance, and lens correction. Once the Lightroom work is complete, it’s a quick run through Photoshop for perspective adjustment, cropping, and final image sizing.

[Mercer Island Project by BUILD LLC]

With a solid kit of photography gear and up-to-date software, the success of a good photo typically comes down the person snapping the shot. Our trials and errors over the years of shooting photos have led to some practices and methods on photoshoots that are worth passing along. Every couple of photoshoots, we get the camera sensor cleaned at our local camera shop. This costs $50-$75 and is well worth the money since Photoshopping the same pesky spot out of hundreds of photos can add up to hours of work and diminishes the quality of the images. Finding the critical window of opportunity on a project can make or break the final photos. Most of our projects allow about a 4-hour window between the last tradesperson finishing their work and cleaning up the site and the owners moving in. We schedule our interior shots during this timeslot as there is typically more latitude (and fewer boxes, tools, etc.) involved with the exterior shots.

[Mercer Island Project by BUILD LLC]

Prior to snapping photos, we walk the site and house to scope out the shots we want. We determine from the beginning which shots will be taken in the morning and which in the afternoon. We also figure out which shots will be captured on the ladder and which from eye level. It’s worth finding any messes and cleaning them up before getting started with the photos (we always bring a small cleaning kit). If furniture or household objects need to be moved around to accommodate the photoshoot, we take a quick “before” photo on our phone to remind ourselves how it all goes back together after the shoot. And lastly, we turn on all the lights and open the shades for the entire house so that we don’t have to remember to do it room by room.

[Mercer Island Project by BUILD LLC]

As much as we like the clean architectural shots (without people), we also like to snap off a few rounds with human scale and dynamic movement. The tripod is essential for the long exposure shots and a room full of people having fun always makes for a lively image.

[Case Study House 2014 by BUILD LLC]

Because architecture changes so drastically in different lighting conditions, we schedule our photo shoots for morning, midday, afternoon, and evening. This ensures that we get the optimal light conditions on each side of a house or building. The evening shots tend to be the most fickle and we typically take several rounds, following the sun down through sunset, dusk, and night. It’s difficult to predict how Lightroom will process the low light shots and a complete range of lighting conditions nearly guarantees that we capture the magic/golden moment (typically around dusk).

[Magnolia House + Guesthouse by BUILD LLC]

We like our social media and being out on a photoshoot is great material for Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook feeds. It takes very little time to grab a quick phone shot once the conditions are right and you’re up on the ladder.

There are also some photography technologies and techniques we’ve been deliberate about steering clear of. On some recent projects it was important to capture roof elements such as green roofs and solar panels. These shots were well suited to aerial photography and we hired Savatgy for their capable flying skills and keen eye for a good shot. Because aerial photography is rather specialized and involves an entirely different kit of tools, we like to leave these shots to the professionals.

[Magnolia House + Guesthouse, photo by Savatgy]

We’ve been shooting for nearly a decade now and this is our personal summary of the most important motives, gear, and methods from the BUILD photography department. This outline should shave a few years off the learning curve for architects stepping into the photography field for the first time. One could argue that professional photographers take better shots, and it’s true, they do. Professional photographers typically have more experience, own better equipment and are dedicated to the craft of photography day in and day out. There is no better assurance of getting excellent photos of your work than hiring a professional photographer. At the same time, given the goals explained above, we find that taking our own shots produces results that fully satisfy our purposes. We also just have a blast taking our own photos.

Cheers from Team BUILD