Recently, Seattle hosted world-renowned architect David Adjaye for a lecture through Space.City, a local not-for-profit organization here in the Pacific Northwest dedicated to the discussion of art, architecture, and urbanism. David heads the London based Adjaye Associates, whose work includes celebrity residences, high profile civic buildings, and even urban work at the master planning level. His résumé consists of visiting professorships at Princeton, the University of Pennsylvania, and Harvard. He’s an honorary AIA Fellow, a RIBA Chartered member, and so forth. David Adjaye is by all definitions, a starchitect.

Because we’re fascinated with his trajectory and admirers of his work, we did our homework on David and his firm, Adjaye Associates. It was during this research that we came across some findings that seem completely antithetical to everything that being a good leader should represent. Via Wikipedia:

“In February 2009, the cancellation or postponement of four projects in Europe and Asia forced [Adjaye Associates] to enter into a Company Voluntary Arrangement (CVA), a deal to stave off insolvency proceedings which prevents financial collapse by rescheduling debts — estimated at about £1m — to creditors.”

A Company Voluntary Arrangement, for those unfamiliar with the term, or too sensible to allow the concept to poison your mind, is a very slick way of stating that the employees continue to show up and work, but without pay — all in the hope that things will change. And just like the paychecks at Adjaye Associates, our admiration came to a screeching halt.

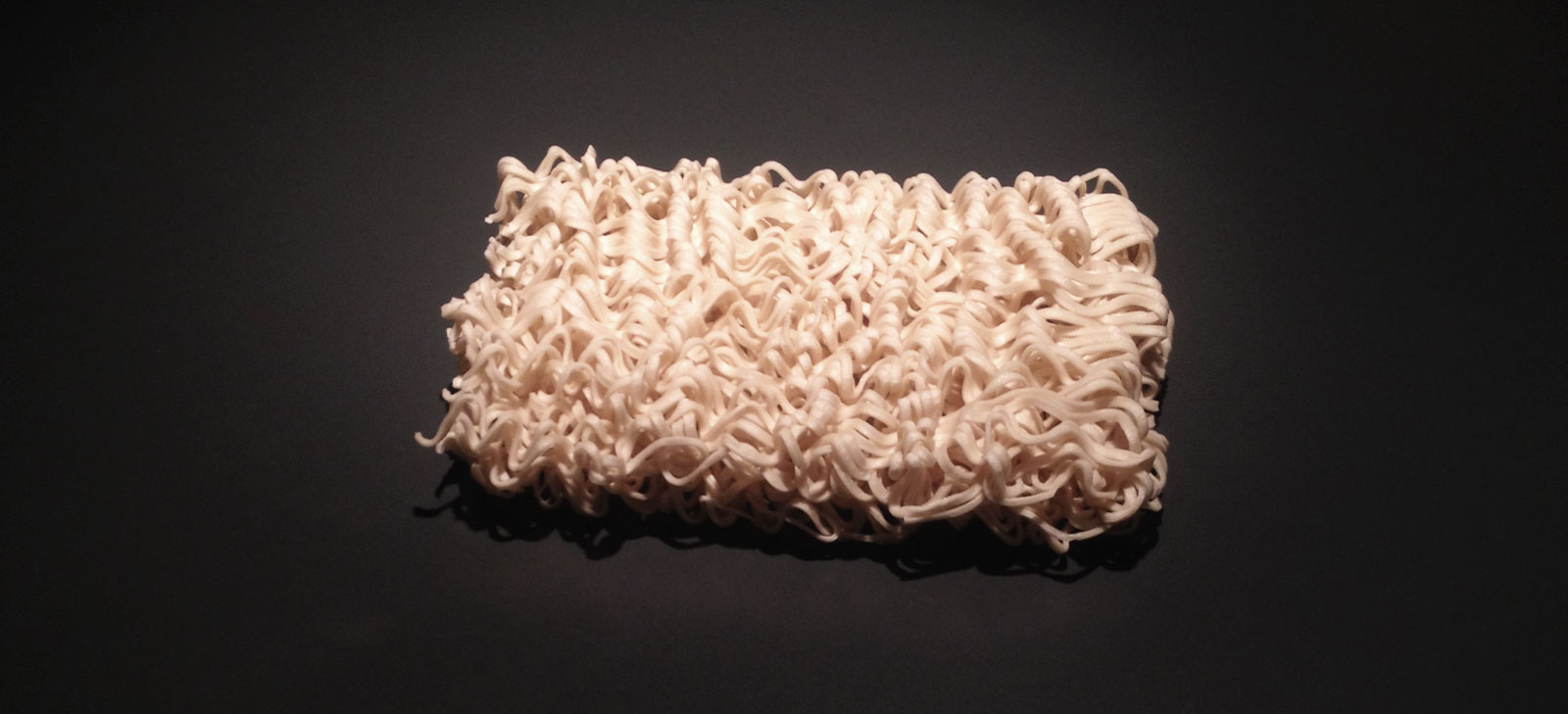

But this concern isn’t really about Adjaye, it’s about the state of architecture. It's about how architects can so readily be lauded for their high profile with little, if any, regard to how they actually run a business. And while we've focused on Adjaye here as a result of recent research, this is a pattern that surfaces time and again in our profession. Why do so many young architects enroll themselves in heroic visions of a career trajectory that not only dismiss responsible finances, but often put their own well-being in jeopardy? The whole situation conjures a depressing image of young architects unable to pay the rent (let alone buy a home) and eating instant ramen for dinner, all while working on multi-million dollar, world-class design competitions all day (and night). What not long ago was the pursuit of starchitecture, has quickly devolved into starvitecture — the sacrifice of everything in one’s life (finances, time, health, general well-being) for the uncertain chance of working on recognized design projects.

Moreover, there's the question of why a client would trust an architect to manage their project and substantial financial interests when they can’t manage their own relatively simple interests. While this starvitecture phenomenon is packaged as an act of ultimate dedication to the design profession, it’s actually teaching career-defeating habits to the next generation of architects.

It’s hard not to compare situations like this to our own financial struggles over the years. As a result of the great recession, BUILD went through a hard stretch of being nearly unneeded from approximately 2007 to 2010. Our strategy was to take whatever work we could, and we managed to stay afloat. We rebuilt and poised ourselves for a resurgence when the times were right; it was the exact opposite of sexy and cool, but it kept us alive and kept us from doing really silly things like not paying our debts and not paying the people working for us. Handling our finances responsibly allowed us to get back on our feet quickly and allowed us to sleep at night.

There is a pivotal, but rarely acknowledged, distinction between Service Architects and the Starchitects / Starvitects out there. We realized some time ago that we are Service Architects. Yes, we design and we always aim to create inspired and beautiful solutions. But, most important, we provide the best possible and most well rounded service to our clients as humanly possible. We’re deeply concerned about the numbers and finances for our clients. A project has to make financial sense for the owner. A project has to work. There needs to be options for a client to get out of a project financially unscathed if necessary. We run budgets and pro-formas and provide whatever research, background, or other expert advice we can. Otherwise, we’re just proposing dangerous fantasies. Part of the job is to understand the finances and subsequent decisions. In the world of service architects, designing without regard to finances is up there with ignoring gravity.

As a profession, we need to do better. We need to take a broader range of information into consideration before glorifying architects. The architects considered to be role models need to recognize that they have duties extending well beyond design, involving business practices and life balance. The young architects coming up the ranks should trust to their senses. If something seems foolish (like working without pay), it probably is.

In our own professional lives, we don’t want anything to do with starvitecture. Architects who are competent at what they do should make a decent living, period. And if starving one’s personal life to feed the professional design-beast is the only way to achieve great architecture, it's time to move on. But we’re hopeful. If the next era of architects, both young and experienced, keeps two feet on the ground, has a bit of business sense, and can balance a checkbook, we're in business. Many of the design portfolios we receive indicate exactly this — sensible design aesthetics, a desire to understand the nuts-and-bolts, and an accounting of how to get it done without starving.

Cheers from Team BUILD