[All photos by BUILD LLC]

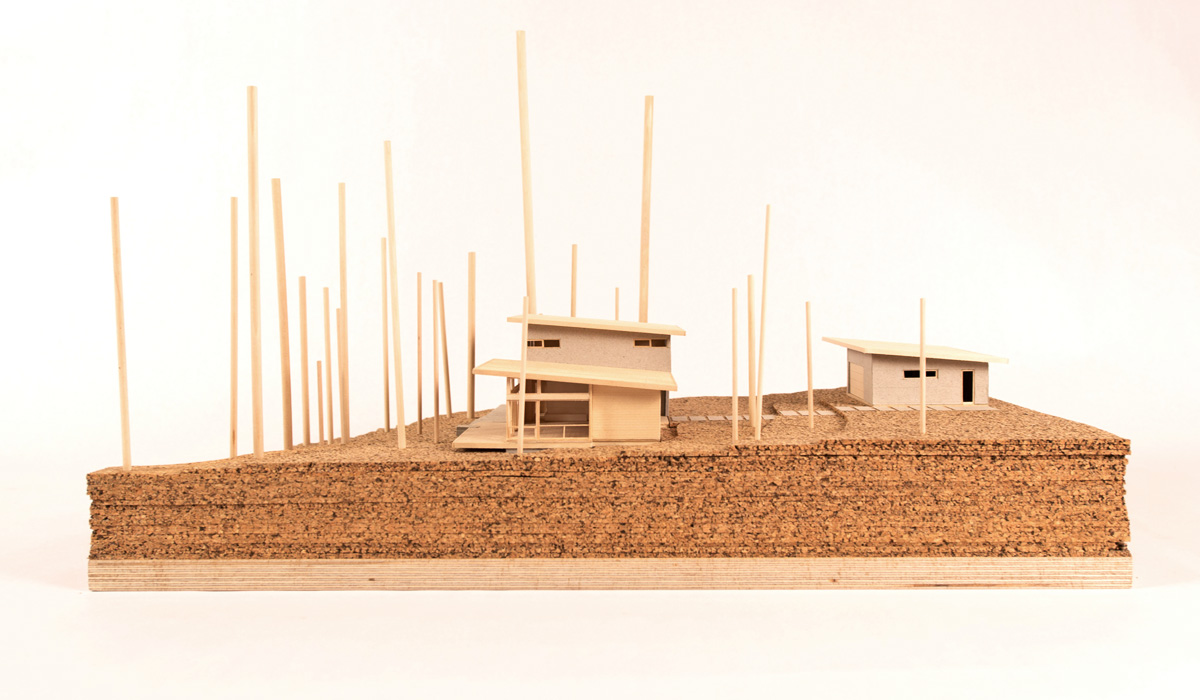

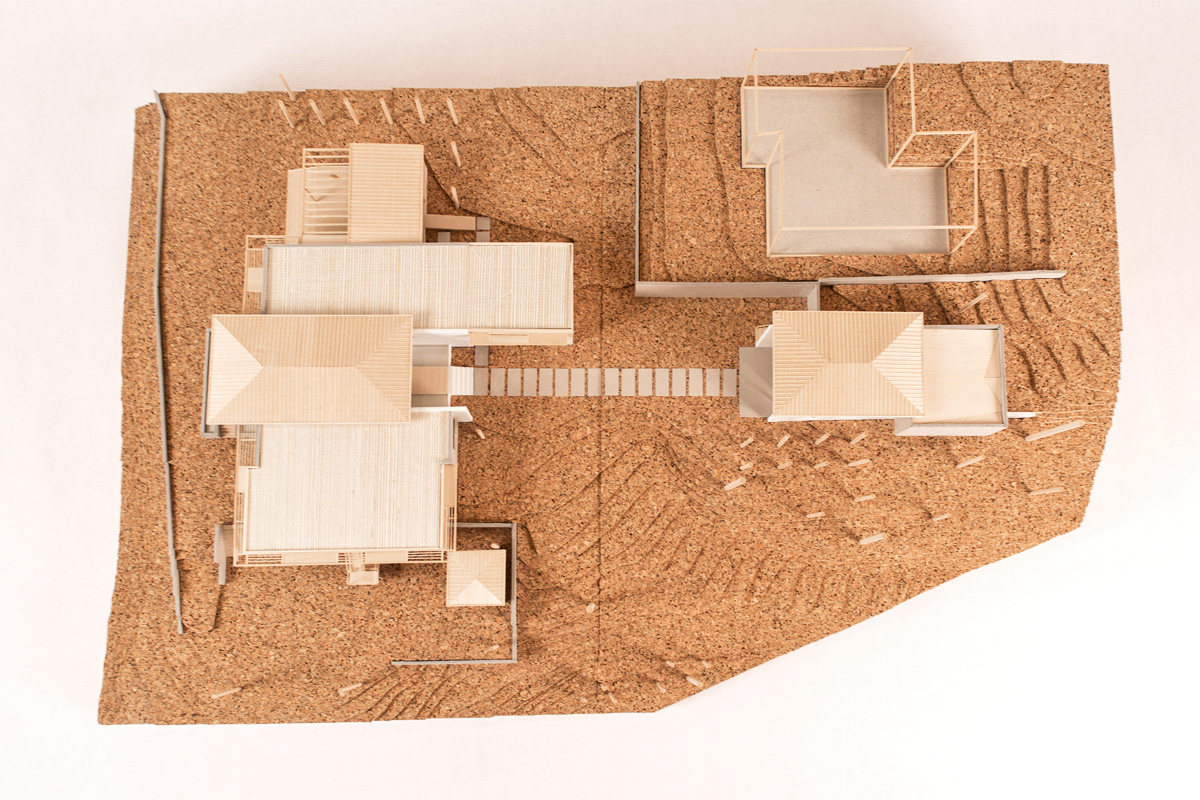

Over this past summer, I had the great opportunity of interning at BUILD LLC, learning and synthesizing the work of the firm through the construction of hand-built models. The experience was rewarding, as every couple weeks my efforts would culminate into a miniature world of a family’s future modern home. The completion of each model provided me with a deeper understanding of the project through the transposition of drawings into the built form. The models served as unparalleled communicative devices that aided my own understanding of the project as well as the rest of the BUILD team and clientele. Today’s post will showcase images of the models I constructed and discuss the materials and techniques used. In addition, I’d like to share how my time spent at BUILD demonstrated to me the inherent value of physical models. For me, the models shown here have formulated an argument for the importance of model-making in contemporary architectural practice.

Materials and Techniques

Materials that respond well to the inconsistencies of the hand are best for building models by hand. Good examples are materials that maintain a clean straight edge, hold their shape overtime, are durable, and possess a texture suitable to the project. For 1/8″ or 1/16″ scale models, basswood is an excellent material for these reasons: it comes in sizes appropriate for typical wall thicknesses, it comes in dimensional structural shapes and sticks, it can be sanded, and it responds extremely well to the blemished tendencies of a hand cut line.

At BUILD, basswood is used in nearly all of the models. Cork, recycled gray board, illustration board, and paper are supplemented to provide different representations (e.g., cedar siding, ground texture, concrete, cement board, etc.). These materials retain their own advantages for particular uses, however do not match basswood’s overall performance on their own. For instance, the recycled gray board that is often used to represent concrete in the models is chosen for its color and texture. It can be more difficult to work with as the fibers in the board make the execution of a clean straight edge by hand a challenge, requiring sharper blades and a good deal of patience. This and other paper materials are more susceptible to warping over time and while basswood is also susceptible, its archival qualities seem to be superior. Material representation is important in the BUILD models, and we use these less awesome materials in addition to basswood to communicate the materiality of a project.

While material representation is important, a high level of craft and technique is even more important to express it. Good craft is not only required for this reason, but also to accurately embody spatial concepts and details. When working in small scales, a fraction of an inch can make all the difference from a well-built model and a poorly-built one. Good planning, a steady hand, patience, material choice, and using proper tools are the best ways to make great models.

High attention to detail at key points of joinery goes a long way and can make up for other mistakes. The edges in a model often provide the points of greatest contrast to the eye. Mitered corners allow for minimal unwanted contrast and provide a crisp and clean edge that mitigates undesirable lines that can disrupt horizontal or vertical volumes. Taking extra time to make sure key wall components are precisely measured and mitered saves significant time down the road compensating for mistakes.

What’s the point of building models?

The creation of constructed space and form within a natural environment (excluding the two-dimensional or digital realms) is the fundamental premise of architecture. To accomplish this, architects use a variety of tools and processes to translate and communicate an idea to built form. Whether created by hand or through digital means, sketches, orthographic projections, and models are the basic tools of this process. However, the only medium of these that exists in true three-dimensional space is the physical model. The model is a key component of the architectural process because it is a scaled representation of an architectural idea; providing real world scale, material and spatial relationships, and implementing context and connection to the site. Of the tools used to express architectural ideas, physical models are the only tools that provide a perception of a built work in a manner that is analogous to the final product.

Hand vs. Digital

Digital tools have transformed the practice of architecture, and the once pivotal role of the physical model has transformed into a controversial pursuit (as evident in the comment section on previous modeling posts). This proposes the question of whether or not it is a worthwhile process at the expense of an architectural firm’s efforts. At BUILD, great value is placed in the physical model, and despite the prevalent use of digital fabrication in the industry, the majority of the models are still built by hand. There are pros and cons to both methods of construction and to discuss these in great detail would require volumes of discourse. Here, I only intend to discuss the benefits of hand-built modeling and how this summer at BUILD has only increased my appreciation for this process.

Building models by hand is a slower process than digital fabrication. This is a good thing! It allows for greater attention to details of the project. And for me, as an intern learning the practice of architecture, I develop a better understanding of the project as the more time spent on individual cuts and pieces provides me more time to digest what is being built. In turn, I become more aware of the project as a whole, I become more of an asset to the team, and I can make better informed decisions providing useful feedback to the architects in charge as it is translated in model form. In addition, this further understanding of the work makes it possible to pick out inconsistencies and discontinuities within drawings that may come about in the modeling process. This is a reality of the architectural process; the construction of physical models brings these oversights out in the open so that they are addressed before the problem presents itself to the clients in a meeting and even the construction site. While creating models by hand, the additional time required studying plans, sections, and elevations of a project increases the likelihood of seeing the unseen.

Conclusion

For the first time since I began my bachelor degree as an industrial designer at Western Washington University in 2004 up through the last two years of my M. Arch program at University of Washington, I was engaged in a design process that was completely removed from digital tools. While my index finger truly missed having a laser cutter, this experience provided me with a greater appreciation for the resurgence of a slow-model movement. Digital tools have made life easier in so many ways and are an essential part of architectural practice, however they are out of touch with the physical world of construction. I have learned that physical models built by hand hold great value as outlets for the further development of a project by bridging the digital realm to the physical. Used in addition to digital tools, they further enhance the designer’s connection to a project. The use of hand-built models here at BUILD allows for greater opportunities to make detailed, informed decisions on a project. As architects it is our role to turn ideas into physical realities and the use of a hand-built physical model enhances this process.

Cheers from Cale + Team BUILD