On a recent trip through Scandinavia, we had the opportunity to stay in a Swedish farmhouse originally built in 1680. It was a learning experience on many levels, and while the home had the quirks and nuisances of any older home, staying there was a pleasure. We were impressed by the flexible open rooms, the adaptability of the spaces, and most of all, the timelessness of the design. The simple A-frame structure was easily updated over the years; new windows, placed in the existing openings, improved the energy savings as electrical improvements, new appliances, and cosmetic updates brought the living experience up to modern day standards.

A couple of days into our stay, our hosts brought out an 8½” x 11” booklet which documents the important design options for building a Swedish farmhouse like the one we were staying in. This simple guide lists the different materials and parts necessary to build the structure, and even covers important site planning strategies. We were astounded that such a guide exists and that we were holding it in our hands. Driving around the Swedish countryside, the similarities between farmhouses were apparent. It was easy enough to assume that there was a collection of design standards passed down from one generation to the next, but to see the entire family tree of design variations illustrated in a tidy portfolio blew us away.

While the dates on this booklet indicate that it was produced well after these structures had been constructed, we’d like to think that it visually documents what was a common design vocabulary over the last several hundred years in rural Scandinavian residential construction. With this in mind, we should refer to it as a retro-active instruction guide for the Swedish farmhouse.

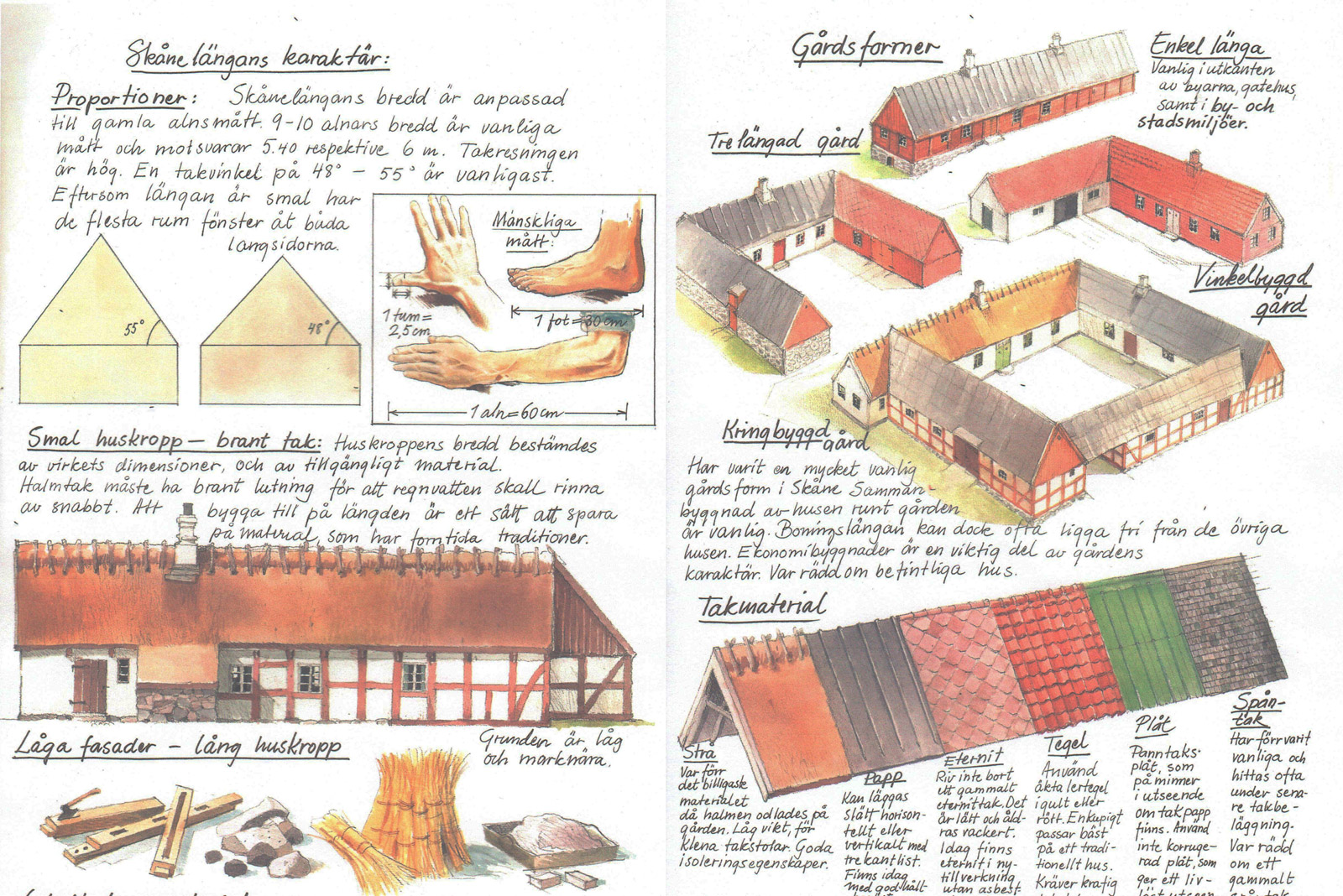

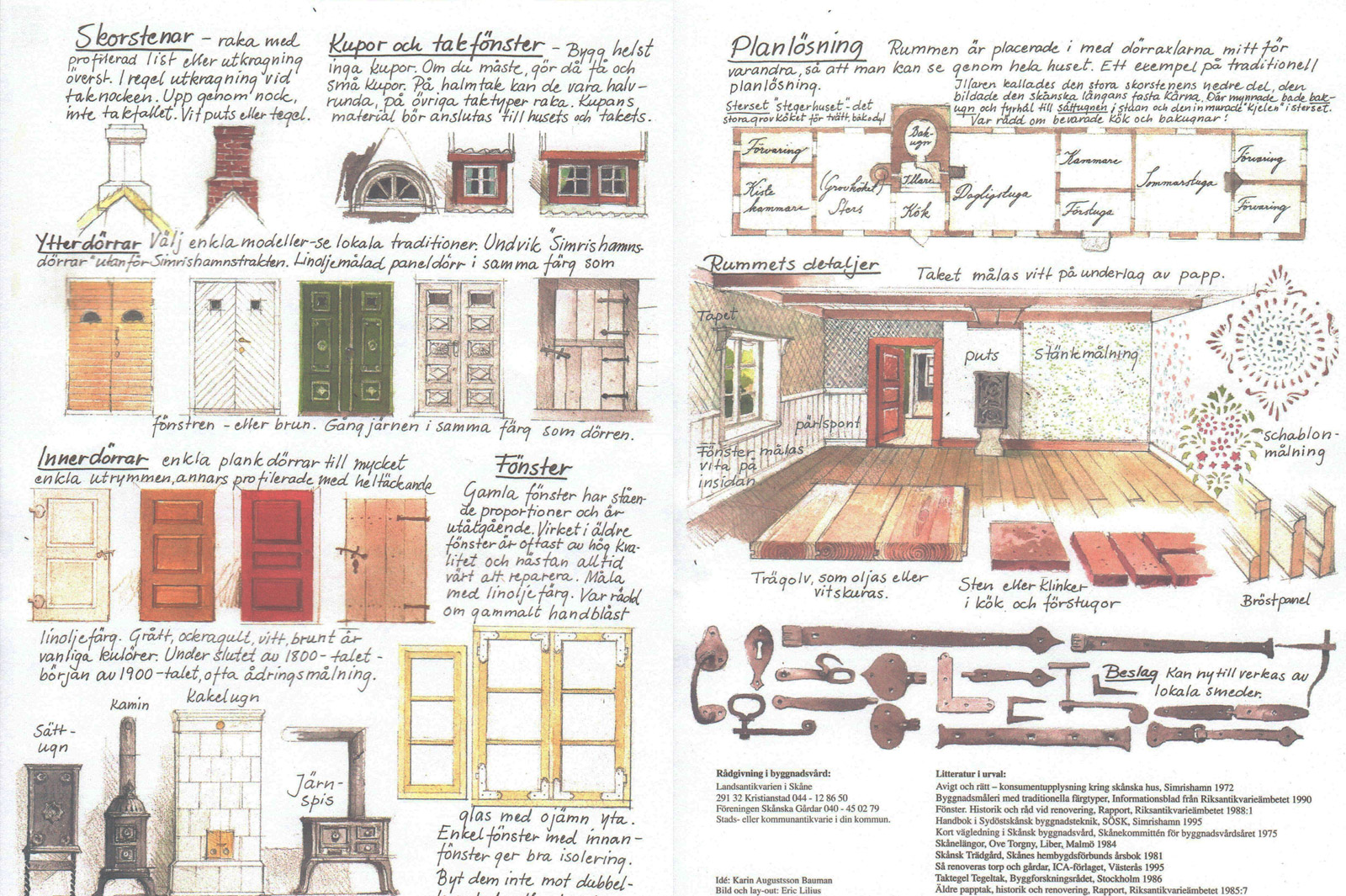

The guide covers an impressive range of design in just eight simple pages; from the site planning and relationship with the garden to the door hardware options. Most impressive is that the illustrations boil down hundreds of years of knowledge into a couple of simple options. The diagrams on roof slopes, for instance, offer just two options: a 55 or 48 degree pitch. For whatever evolutionary reason, these are the two roof slopes that make the most sense for this type of structure in this environment. The same goes for the configuration and attachment of the barn structures to the living quarters. Studying the illustrations, you get the impression that these guidelines are the result of generations of trial and error; that these design solutions exist for a reason.

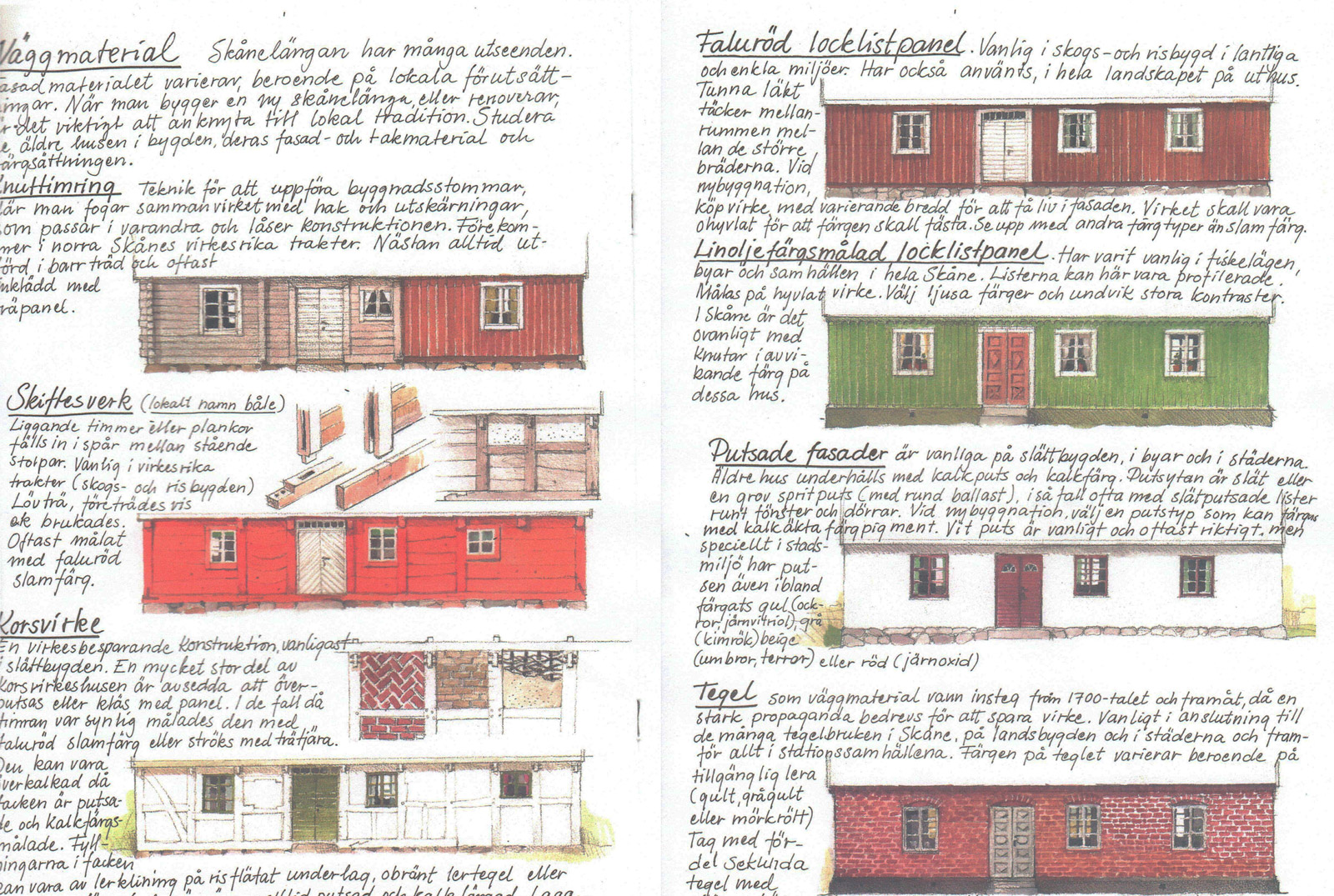

There is a refreshing sense that the material options are local and practical to obtain. The sustainability is already built into the design, with the option of bringing bespoke materials from exotic places removed from the equation. The same can be assumed of the construction methods, it would appear that the building techniques depend on resources directly available within the community.

While the guide is regulating and pragmatic, this method of design probably didn’t feel restrictive to homeowners when these farmhouses were originally constructed — in fact it probably still doesn’t feel restrictive in Scandinavia. There are a variety of options to fulfill a homeowner’s desire to make personal choices, and ample opportunity for each farmhouse to be unique. The important element is that this design freedom all occurs within set boundaries defined by sensibility; by what works and what doesn’t, by what is available and what’s not, by the practicality of time and budget. There are six varieties of roofing, seven types of siding, and nine distinct door designs. These three variables alone allow for 378 unique farmhouse designs and while one completed design could vary from another, each individual design decision is manageable. The nine door options are locally made from community resources, not a thousand from every corner of the earth. The same philosophy of decision-making applies to all aspects of this guide: Design decisions are informed by the collected knowledge of the people who built a house before you did.

As architects, designers, builders, thinkers, and people who live in homes, this little guide really has us thinking about our philosophy of design (and our philosophy of life, quite frankly). Since returning home, it's been impossible to ignore the stark contrast between the method of design and construction prescribed by this little booklet and our observations in the United States.

Without a doubt, this guide to Swedish Farmhouse Design strikes a delicate balance. Too much standardization, and you get the endless repetition of suburban tract homes loathed by anyone with a design pulse. But the opposite end of the spectrum is equally harmful to the built environment. Without design discipline, the built environment doesn’t make forward progress in terms of sustainability and creating healthy environments. Without the careful curation of design options, homeowners all too often end up with a project that is over-designed, over-stylized, and over budget.

Using local methods, materials, and labor narrows down the design choices and clarifies which options are the most sensible. Employing a healthy dose of sensibility fosters design that responds to its immediate environment and prevents materials from being unsustainably shipped from halfway around the world. These decision making skills are important design tools on a project and they help create spaces for living and working that are relevant to specific environments for generations to come (also known as timeless).

While American culture loves to “re-invent” design, we can’t help but wonder if the very nature of re-inventing something like the single family residence is counterintuitive to good, sensible design. Among the important messages to take away from the Swedish Farmhouse Guide is that the design of something should be based on the lessons learned from the entire lineage of past designs similar in nature.

Standardization may sound too harsh to apply to residential design (or it simply brings up visions of Suburbia), but when applied correctly, it provides a sense of reason and can lead to exceptional results. This little guide makes a good case for a recalibration of how we think about design in the U.S. and also sheds light on a design profession that practices with purpose, reason, and conviction. We’re incorporating more of this thinking into our own design process here at BUILD and we’ll be sharing more of our experiences soon.

Until then, cheers from Team BUILD