[All images courtesy of Penguin unless noted otherwise]

In spring 2017, we sat down with author, professor, and then Buro Happold Engineering principal, Kate Ascher. Knee-deep in her West Coast book tour, we caught up with her in Seattle to discuss her mesmerizing trilogy on urban infrastructure, the power of a good graphic, and understanding complex systems. You can read Part 1 here.

You’re in Seattle speaking about your new book The Way to Go: Moving by Sea, Land, and Air. How has the city treated you so far on this book tour?

Seattle’s great—it’s like a happier, prettier London. Aside from coming to Seattle on book tours, I’ve spent time here when I worked for the Port in the ‘90s then again in ‘05 and ‘06. I know the waterfront, but I get lost when I move away from it.

[Photo by BUILD LLC]

Which cities or communities do you consider to be the role models of infrastructure in the world?

Some South American cities are models of transportation because of their experiments with pedestrian connections, forward progress in bus rapid transit, and all kinds of civic transit programs. London is a great model with its congestion pricing and initiatives to keep cars out of the city center. Those are cities that have pushed the boundaries with respect to transportation. In this country it’s a little harder to identify role model cities, as there aren’t any that have truly revolutionized transportation, and all are beholden to the federal government for funding. But a lot of cities have come a long way. Seattle does a pretty good job of looking forward. I see your busses running around on the catenary system downtown and a lot of other stuff that we could never make happen in New York. Is there a model city? It’s hard to say. So many cities are good at different things. The problem here is that this country is basically broken in terms of infrastructure funding from Washington. As a result, American cities are not really role models for the rest of the world. There are a lot of foreign cities that set a much better example.

Do you enjoy spending time elsewhere in the world to study those systems?

You bet. I travel internationally from time to time for my academic work with Columbia University. I love going to a new country and figuring it all out. I recently put together a conference on waterfront development in Istanbul, Mumbai, Rio, and New York. I do a lot of waterfront transportation work, and you have to go to those places to understand it.

You are a principal with Buro Happold, which has a very compelling line on their website, that they “deliver projects that do not cost the earth.” What are some of the more earth-costing systems you’ve encountered in your work?

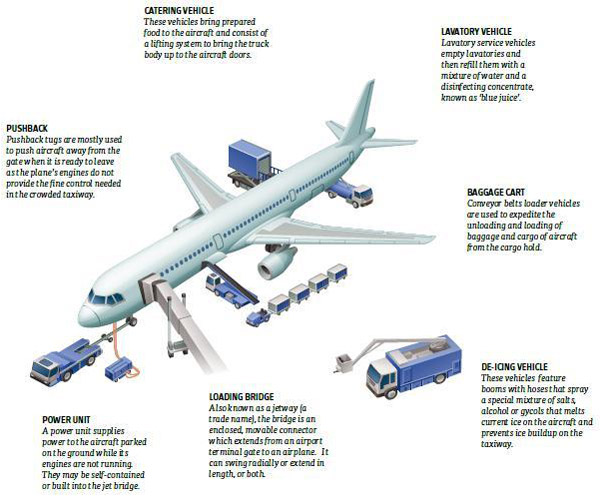

Unfortunately, human life wants what it wants. For instance, the climate impacts of jet fuel are terrible. Airlines are deregulated and the masses have unlimited access to cheap air travel. Because of this, there is tons of particulate matter all over the ozone that never used to be there. But nobody is stopping airplanes—in fact, they’re just building them bigger. The question then becomes mitigating some of the things we consider to be “quality of life” issues that are actually undermining our environment.

You can look at almost any mode of travel or energy production this way. Buildings are another good example; while some structures may be considered “green,” they are draped in glass and retain almost no heat. Consider the energy involved in making these tall buildings in the first place. There’s no way to truly calculate the environmental impacts. Where do you start? Buro Happold does a good job of trying to understand the effects and balancing what clients want with the environmental considerations. But it’s difficult because the clients are working in a competitive world; they want to have an attractive building and they need to secure an anchor tenant. You get into the cycle of trying to balance competing interests.

Is Reduce, Reuse, Recycle working for America?

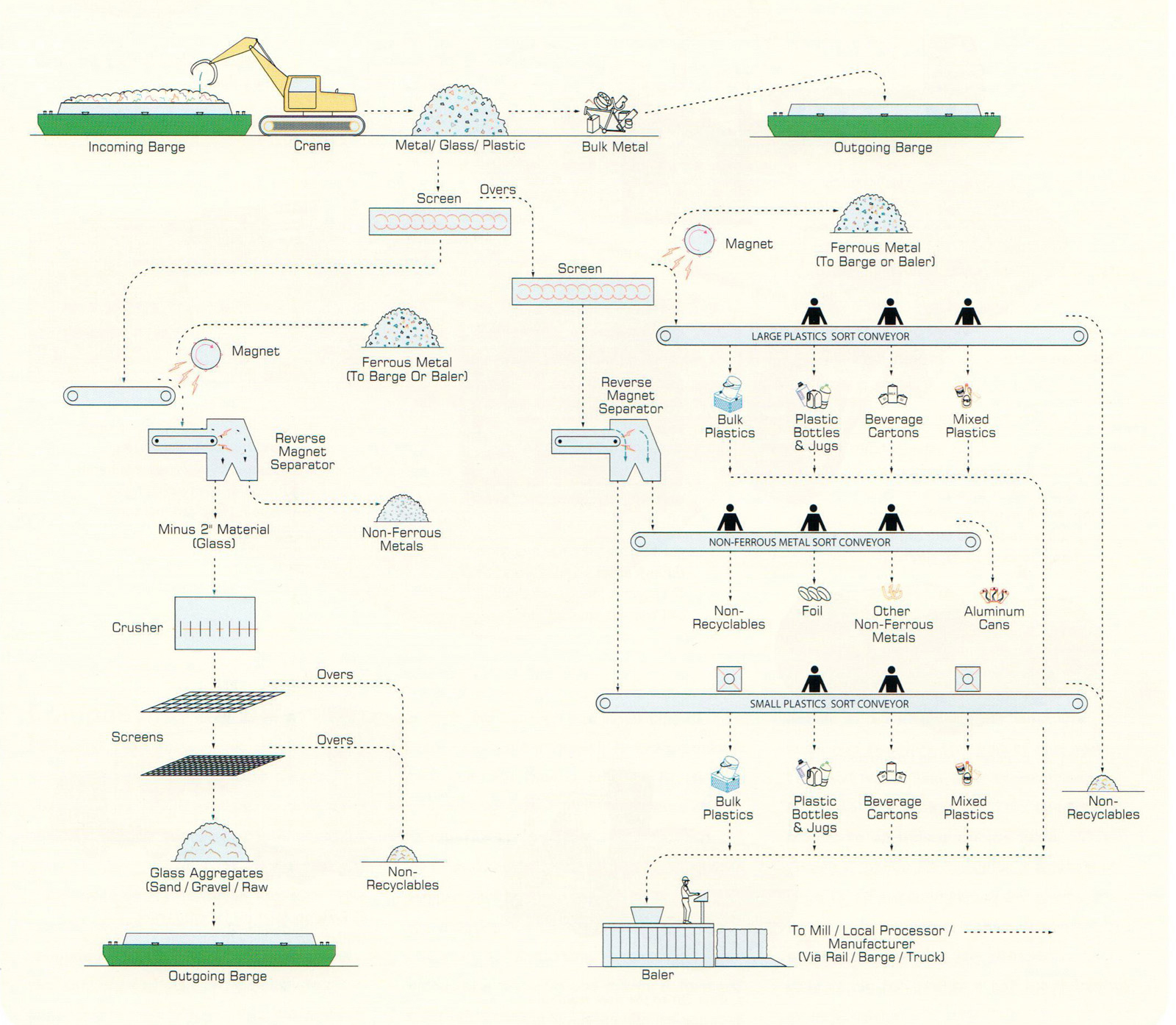

No. Not compared to other countries. We’re terribly wasteful here in America. I had a guest lecturer in my class recently from the Bjarke Ingels Group in Denmark and he was talking about what the Danes are doing. They’re recycling 45% of their waste, incinerating 50%, and sending 5% to the landfill. You’re probably closer to that in Seattle, but we’re nowhere near that in New York. The packaging alone that we have on things is ridiculous—you can’t even open it! What’s so precious inside? Why can’t you just put it in a paper bag? If we started with the packaging issue, the garbage issue would be a whole lot easier.

Denmark and the rest of Scandinavia seem to have a lot of this stuff figured out. For centuries they’ve been pushed up against their physical boundaries, which might cause them to think more conscientiously. Do you think their progress has to do with the limitations of land?

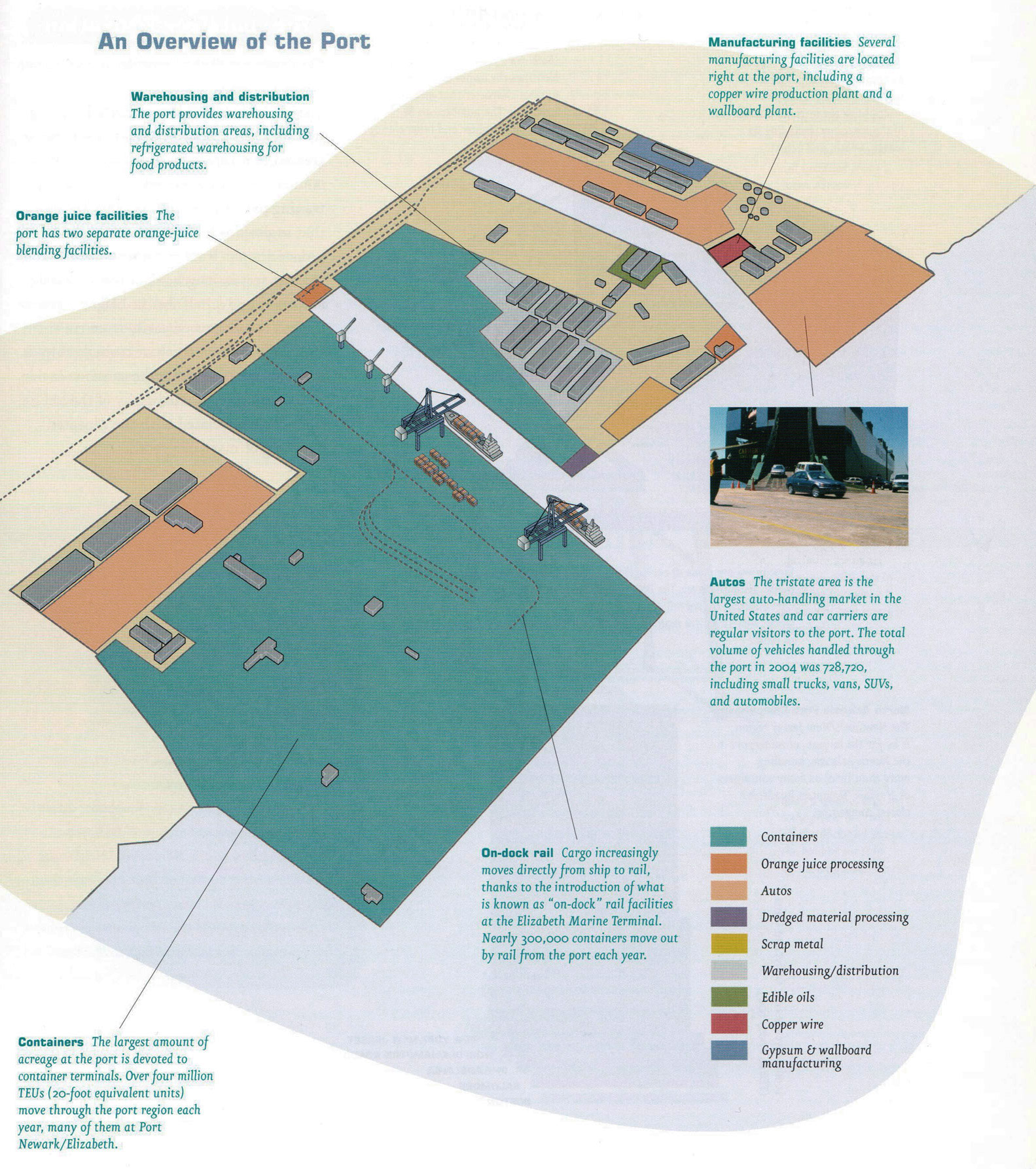

Absolutely. I used to work at the port in New York City, back when they had plenty of space. We had containers everywhere, each with its own set of wheels, and the tracking process involved a guy looking at the labels on each container by hand. Meanwhile, foreign ports, which had less space, were organizing containers six-high and each of them was tagged for computerized tracking. They knew where each and every container was. These computerized systems have existed for a long time but New York never needed them because they had plenty of space. That changed over the years and the port no longer has abundant real estate. I recently visited the port facilities near Newark and the change is enormous from what it previously was. The containers are stacked and a new system tracks them as they enter and leave. That’s just a small example, but we’ve always had so much land that we’ve just sprawled and sprawled. Now that sprawl is costing us a lot.

Your books focus heavily on the city. What are your thoughts on the American suburbs? Are they working?

Suburbs? They’re a lovely place to grow up, but I didn’t want to raise my kids there. It’s not as safe in the suburbs anymore and they seem to be more and more homogenous. However, suburbia remains an important part of the urban equation. They are a natural complement to the city. You can’t cut the suburbs off from the city, there will always be people who work in cities but want something akin to a quasi-rural existence.

Do you see solutions for the suburbs or do you see them getting worse?

Like cities, suburbs have a way of reinventing themselves, and they go through peaks and troughs. A lot depends on corporations and where they want to be located. One minute corporations want to be in the suburbs where it’s cheaper, but the next they want to be in the city. Then next they’re splitting their operations. As the tax bases of the suburbs change, the suburban towns change. They’ll always be a necessary appendage to the city.

How has New York changed for you in the last decade?

It’s become better and better. The subway system has improved, and the park system is much more robust and comprehensive. Crime is down, and a couple of big transit and infrastructure projects are underway. There’s still some shaky elements, such as the electricity transmission system and subway crowding. But people are focusing on NYC in positive ways, and it’s a magnet for young people, which gives it an energy and lifts the city up.

You’re sometimes called on as a resource by the news media when things go awry with systems like the power plants or electrical networks in New York City. Is that because of the books or your role at Buro Happold?

Probably because of the books. Most of the time when it’s really technical, I turn them down, though. I have no idea why the steam pipes burst, but neither do most of the talking heads on these programs. Some of the scientists or engineers, who get really technical, know why, but even they don’t have full information about a specific situation as soon as it happens.

Having worked with large jurisdictions like the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, what is your advice to architects and planners on how to best succeed with city and state agencies?

A lot of it is understanding the political drivers. By background, I’m a political scientist of cities and it’s helped me tremendously in understanding political agendas, the flow of money, and elections. If you have your feelers out for these matters, you can pretty much predict where people are going to come down on certain projects and ideas. My suggestion is, before you design a beautiful project, talk to the people in power and see if it’s feasible and what would have to happen to align the stars. Very often, these projects are not going to happen.

Occasionally I sit in on design juries for architecture students at Columbia University and I wonder why they aren’t given real world problems. I know it’s part of the training as an architect to do creative designs, but why aren’t we more often giving these students a real-world context to design around? Give them some external factors so they can marry good design with resilience, politics, law, and the realities of finance. If you don’t add these factors into the equation, you’re wasting your time. Design alone is nice to think about, and as a graduate student you may be picking up new ideas, but you’re no further along in putting these ideas into practice than if you’re playing make-believe.

What are the infrastructure challenges that the next generation should prepare for?

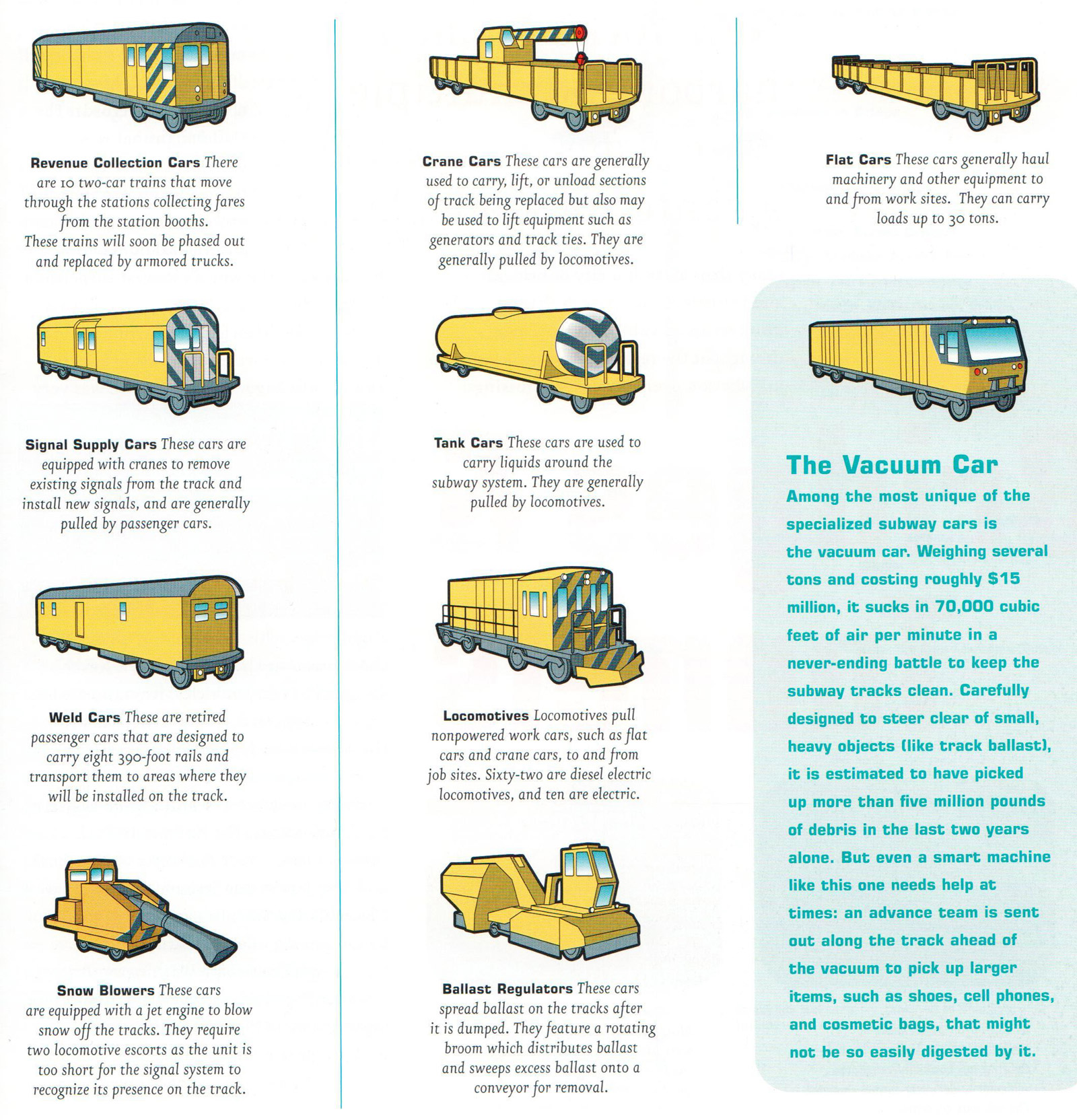

Some of the legacy systems that are still working are not going to last forever. In Manhattan, these include the water system that’s 150 years old, and the subway system that relies on old technology. The question is how to fund the replacements or upgrades of these systems. They’ve more than paid for themselves over their lifespan, but to replace them is so much more expensive. Cities are denser, there’s more cost involved in the planning, reviews, construction, mitigation, etc. The system isn’t set up to find the money to pay for all of that. Because cities are denser, we’re more dependent on these systems than ever, and we have a huge problem if the upgrades don’t work.

Are there mistakes that you see cities or jurisdictions making time and again?

Not necessarily the same mistakes, but you’ll often see egomaniacal decisions made by politicians who simply want to be regarded as doing something. It’s completely wasteful. The Mayor of New York closed the Fresh Kills landfill to make Staten Island happy because he needed their votes. So for 15 years we in New York haven’t had a place to put our garbage and the cost is enormous. The Governor of New Jersey cancelled a rail tunnel to be built under the Hudson River simply for political reasons. The project already had federal environmental approval, the money was allocated, and the site was selected.

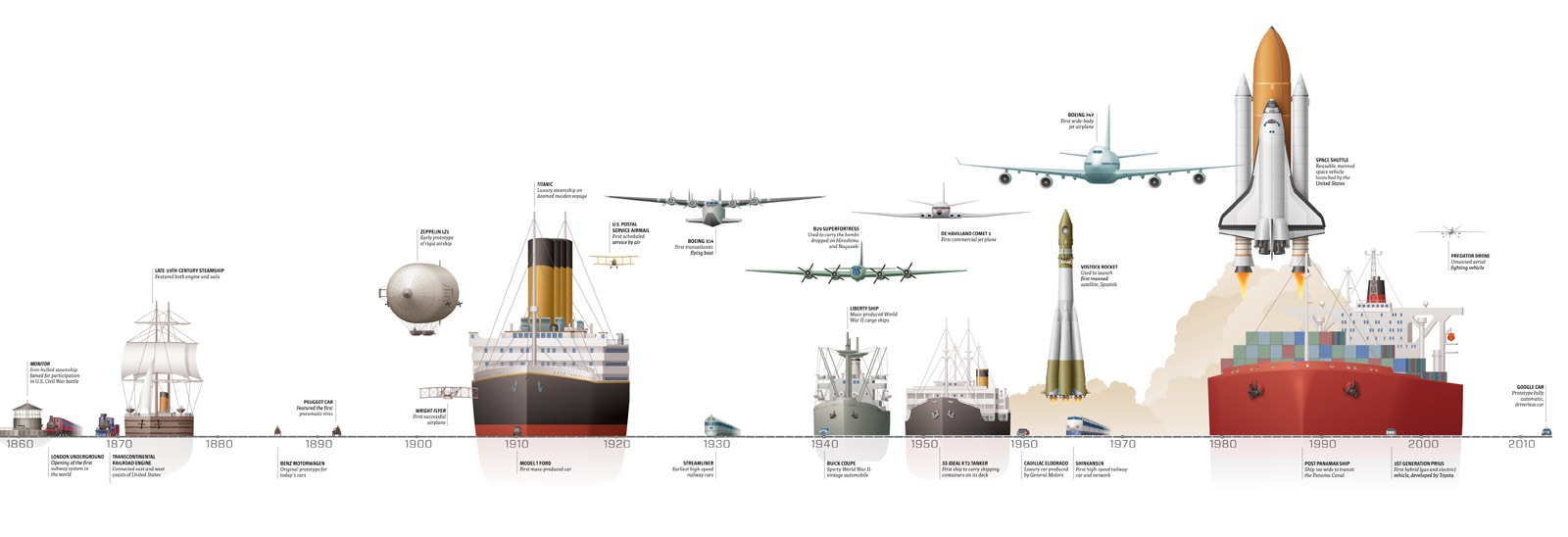

Kate Ascher worked at the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, the New York City Economic Development Corporation, and Buro Happold Consulting. She serves as Milstein Professor of Urban Development at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture and Planning. Her books include The Works: Anatomy of a City, The Heights: Anatomy of a Skyscraper, The Way to Go: Moving by Sea, Land, and Air.