As architects, we think of ourselves as a pretty thoughtful and progressive group. We like to think that we leave things better than we find them. And, although we are in an industry and region with pretty inflated financial barriers to entry, we maintain a disciplined and responsible approach to spending the hard-earned funds our clients trust us with. Thrifty isn’t necessarily the word for it, but we provide great value for the time, energy, and dollars entrusted to us.

A friend once told us, “Liberalism is wonderful as long as you don’t mind paying for it.” We believe that paying a fair share of taxes and “user fees” (a ubiquitous term now used to cover everything from supporting state parks to applying for building permits and then some) is the bedrock parameter for maintaining a civil society and a community we’ll continue living in. This philosophy makes common sense to us and we don’t at all mind paying to fix potholes, uphold life safety in the built environment, keep city pools open, and allow some element of access to community for everyone. You know, the basic covenants America was based on.

But lately, we’ve noticed something very disturbing, and it’s become an increasingly troubling pattern. At a time when our industry is finally rebounding from the recession, we see a new threat on the horizon — a bureaucratic embellishment of sorts, along with “user fees” that have tipped to unprecedented and unbalanced levels. Here are our own personal, first-hand, real-world experiences indicating that things have tipped:

Excessive fees by regulatory groups

A recent project of ours required that the city sidewalk in front of the remodeled residence be replaced. The requirement isn’t unusual, however the permit fees for the sidewalk alone cost more than the actual tearing out and replacing of the sidewalk. If the project was located along the busy corridors downtown, such fees might be justified. But in an outer neighborhood with low pedestrian traffic, excessive fees like this indicate that something is ridiculously out of balance.

Overreach by third party inspectors

Third party inspectors are additional design professionals that the client is required to hire to ensure conformance with the building code. In the past, city and county building inspectors would conduct this work, while the building permit fees would cover the time for performing site inspections and the accompanying administrative work. This system took a pivotal change in the last decade and it’s now common for building departments to farm this work out to third party inspectors.

Another recent residential project involved four geotechnical site inspections and related reports, totaling less than 8 hours of site time by the third party inspector. Yet, the billed cost of this observation and related administration was $7000. And the kicker: the services and related city fees totaled more than the actual physical work and material costs of the excavation, material placement, drainage system, and backfill. You read that correctly. The watching of the work, cost more than the doing of the work. Again, when the paperwork and inspection fees exceed the cost of laborious site work, the alarm bells in our minds start sounding off.

Architects are becoming Permit Technicians

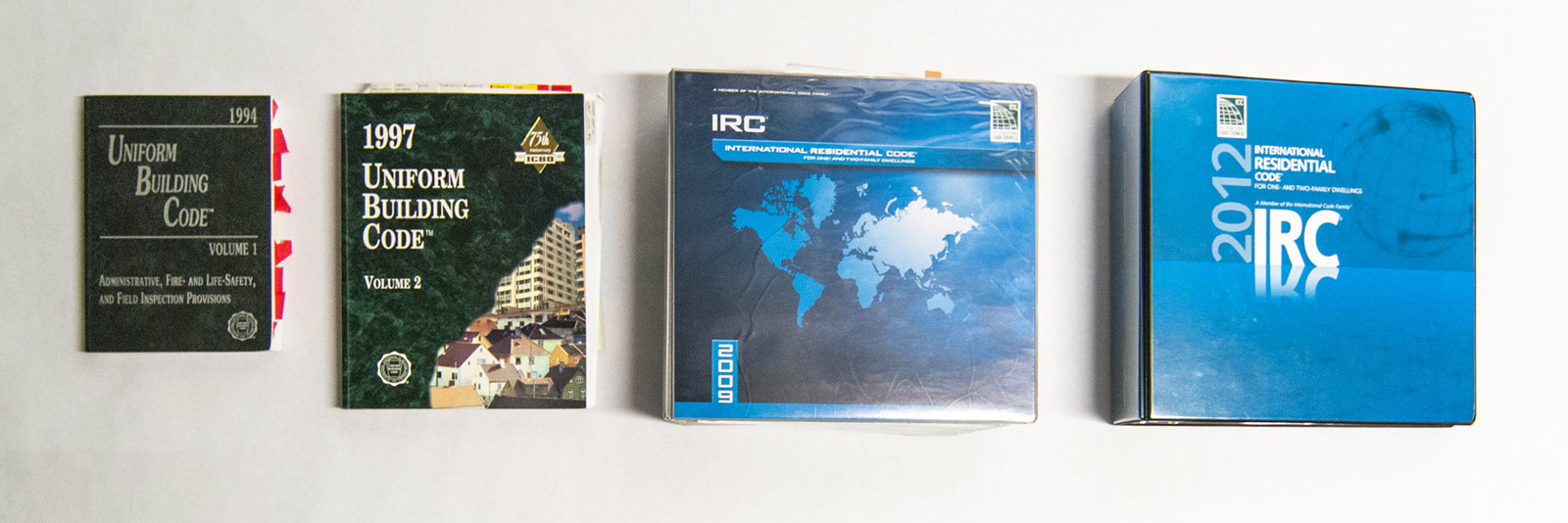

The photo above features most of the building codes that an architect must satisfy in order to submit a residential project to the building department for permit approval. These books get a little larger with each release and the amendments from state, county, and city jurisdictions continue to add to the complexity. The photo below shows the growth of the code between 1994, 1997, 2009 and 2012.

We like meeting (and exceeding) the requirements of the building code. We like designing buildings that are environmentally responsible, structurally sound, and safe for the inhabitants. But the amount of time required to satisfy the permit review process is becoming excessive to the point that it’s jeopardizing doing good architecture.

We know what you’re thinking: Meeting the building code and designing the building should be one in the same. And we couldn’t agree more. However, the permit submittal process is quickly evolving into a set of documents that serve the bureaucratic process alone, mutually exclusive of the construction documents. A few examples include drainage calculations that become mathematically abstract, impractical temporary site provisions (wrapping the trees in plywood for protection, really?!), and unrealistic furnace specifications intended to address policy rather than the reality of heating a home. Many of these requirements become mere exercises in checking boxes, reverse engineering, or worse: gaming the system to produce the desired results. All of this competes with the bandwidth required of the more significant and tangible aspects of architecture, like the nuts and bolts of the structural system, coordinating with the manufacturers for the most appropriate products, and creating a piece of architecture that will be a value add to the built environment. Not to mention, actually focusing on making a project more sensible, sustainable, and low impact. Architects are becoming permit technicians at the expense of doing good architecture.

Overlapping Liability

Most of us architects were trained by schools subsidized by the state, we take professional state exams, we maintain professional state licenses, and we are required by the state to carry professional liability insurance to cover the work we do. With all of those checks and regulations in place, it’s a shame that the state has to then police an architecture project down to every last detail. For instance, it seems unnecessary for a building department to concern themselves with something as granular as providing adequate ventilation at the roof of a new residence. No doubt, ventilation is very important, and any architect worth their education, license, and liability should know this. But the fact of the matter is that if the ventilation isn’t properly designed, the architect will have a host of obligations to face entirely independent of the building department. Obligations such as contributing to the solution, (be it financial or sweat equity,) relying on their liability insurance, getting sued, or having their license revoked. Instead of the checks and re-checks of an architect’s work via the lengthy permit review process, maybe architects who don’t understand the basic principles of construction shouldn’t be given licenses in the first place. There seems to be too many layers of scrutiny on projects and not enough emphasis on an architect’s training.

Ambiguity of accountability

A current design project of ours is sited approximately 500’ feet from a possible eagle’s nest. Given that bald eagles were recently on the endangered species list, there are typically requirements for a construction project within a certain radius of the nest. Easy enough. Get the requirements and incorporate them into the project, right? Wrong. This seemingly straight-forward task required a dozen phone calls to The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, 11 of which led to pre-recorded message loops, inactive voice mail boxes, WDF&W employees unfamiliar with the issue, and other black holes of a nebulous state-operated phone routing system. WDF&W employees moved on (left their jobs) without forwarding information, emails bounced back from the replacement, and no one was returning our calls.

Finally, a representative directed us to the eagle hotline (there’s a hotline?!) where we left a message which was returned several days later by a very helpful gentleman who told us to call another guy who directed us to a list of guidelines on the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Services website. Finally, something in writing! As it turns out, since bald eagles were recently delisted from the endangered species list, the list of guidelines is now just a handful of recommendations. Fine, no problem, happy to comply. But shouldn’t someone at the building department, or a majority of the folks at fish and wildlife departments know where to point an architect for this info? Surely we aren’t the first (or last) to inquire about this requirement/recommendation. Wild goose chases like this cost architects, builders, and homeowners a lot of time. Time that could be better spent designing and building better buildings.

The way we see it, the excessive fees and disproportionate time required of the permitting and inspection phases of a project are clear indicators that the needle of the sensibility-o-meter is red-lining. The system has tipped into a dangerous zone, and not only has the process become inefficient, it’s become wasteful. A clear vision of the seas we’re all trying to navigate is becoming obstructed by the tidal wave of hyper-regulation. It’s situations like this that paralyze communities, cities and societies, and if you ask us, it’s time to sound the alarm bell. Most of us (architects, builders, trades-people, plan reviewers, inspectors) want to do work we’re proud of, work that is environmentally responsible, work that makes the built-environment better, work that gets us excited when we hop out of bed in the morning. There are no enemies here — we’re all after the same goal — but we need to work more intelligently, resourcefully, sensibly, and with more accountability.

As always, we’re open to your thoughts.

Cheers from Team BUILD