Earlier this spring we were invited to attend a series of student architecture presentations. Which, in and of itself, is nothing newsworthy; we sit in on architectural juries regularly for the University of Washington and Washington State University. Throughout academics and our professional careers we’ve probably been involved in nearly a hundred architecture presentations (or crits as we called them in school). But this one was unlike any previous crit we’d been part of; this one was unusual. You see, these architectural presentations were being delivered by grade school students -3rd, 4th and 5th graders to be exact.

We immediately conjured up images of gooey gingerbread houses and babbling children; crumbly eaves lined with gum-drops and runny-nose kids stumbling through poorly memorized explanations. We couldn’t have been further from correct.

Each student at the University Coop School politely took their turn in the spot light and delivered their design thoughts with nearly as much clarity and purpose as the college students we regularly review. They had reasons for their design decisions; they had worked through a rational and sensible design process; they believed in their projects. It was astonishing.

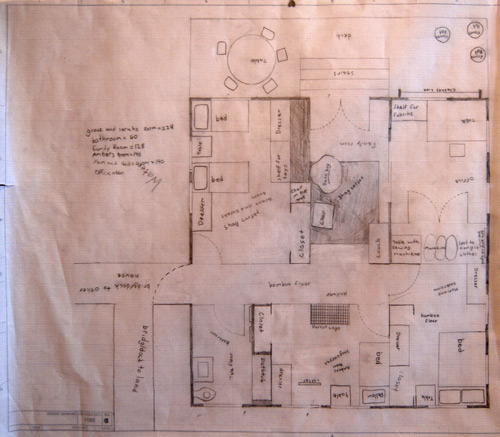

And the work itself, you ask? It was great. There were real architectural ideas being explored. The site plans had been taken into consideration, there were floor plans drawn up, heck there was even a window schedule in someone’s presentation. A friggin window schedule, we were well into our twenties before we ever generated one of those. And the designs were cool, they evoked thought and dialogue. There were discussions about how roof forms differ between Japan and North America, the merits of site vegetation were reviewed, fresh air from operable windows was touched on. Best of all, the kids were having fun, they were totally into it. We were floored.

Our minds raced toward the inevitable; what was at the root of all this? How was the quality of the work and caliber of the discussion this good among a room full of grade school students? Had the latest round of university level crits that we’d participated in been so poor that it diminished our expectations? Nope, the last several crits had been quite good, actually. Were these 3rd through 5th graders prodigy children? Perhaps, but there was something else at play here. Were we being bribed with girl-scout cookies? Negative. Had we been out too late the night before? Go fish. The more we thought about it, the more we realized that what made this experience special wasn’t anything at all; in fact, it was the absence of something.

What was missing from this crit was that thick layer of esoteric nonsense that typically accompanies any academic architectural presentation. All those cryptic excerpts from starchitects and references to obscure French philosophers; all that trendy vocabulary and those made-up terms that don’t appear in dictionaries of the English language. It just wasn’t there at all – it’s like it missed the bus and never showed up… and it was great.

Without the archi-nonsense (how’s that for a made-up term) the work and the discussions were authentic, there was a raw honesty that, more often than not, only a child can invoke. Throughout the afternoon’s crits, there wasn’t a single reference to Frank Gehry, none of the projects utilized ridiculously fashionable materials like cor-ten steel, and it may be the first crit in the last decade that didn’t include a single project influenced by Herzog and de Meuron. There was no “blurring of the boundaries”, there wasn’t any theoretical “dialogue” between the building and the landscape, nobody used the word “techtonic”. It was, in a nutshell, refreshing.

Everything the students talked about came from the gut. The architectural ideas that they were being explored were real; they were concepts that you could make out of a box and ordinary people could understand the discussion.

We need more of this in architecture (or less, depending on how you look at it). We need more raw honesty, more genuine convictions and straight-forward discussions. That layer of nonsense that went missing allowed for more creativity, it led to more productive explorations and it produced architectures that people can understand.

In so many ways, the archi-nonsense limits us. It puts boundaries on how we think and communicate as architects. These kids, whether they knew it or not, blasted right through the protocols of architecture and, subsequently, it allowed them to truly explore form, function, color, texture, etc. They were unbridled and sincerely imaginative.

So hats off to University Coop School department of architecture from team BUILD.

Got a story of unbridled imagination? Share it.