Not long ago we met up with some buddies who are professors at notable architecture schools around the country. We talked shop, we had many a drink and we got into an interesting discussion about architecture, academics and the profession. Us being architects who get things built and them being architects who teach young people how to become architects, the conversation inevitably hit on an important question; what is happening in academics to prepare the architects of tomorrow? How are they training students to keep their feet on the ground? What is it to think and design in such a way that ideas and drawings can be practical and realistic? How are they teaching the next generation to be the type of architects that get good design built? Not two sentences into their answer the terms pedantic and didactic were employed with professorial authority. <insert rolling of eyes here>

Now, it’s good to be well educated, it’s advantageous to have a command of the English language, and it’s smart to keep some high-flutin words on call to shape conversations and communicate precisely. But that the conversation immediately brought in such vocabulary is a glaring red flag to us. This is a profession that depends just as much on an architect’s conduct in the field as in the office and if we talked like that on the job-site we’d get nothing but blank stares and an alarming range of end results.

It’s not that architects shouldn’t learn to communicate at an academic or culturally refined level. That’s not our point here; architects need to be better versed in communication than most professions. Architects need to cover the full spectrum of communication; we need to be able to properly communicate with the likes of a graduate level jury on one end, an immigrant dry-waller on the other end and everyone in between. What concerns us is that a down-to-earth, hands-on type of language isn’t being taught along the educational path of an architect. This language might be seen as narrow-minded in and of itself, but it’s critical to the overall picture and it’s necessary to getting buildings built. It also lets people know that you put your pants on one leg a time like everybody else.

Seeing as how academics are taking care of the highly-refined and sometimes cryptic side of language, we’re going to tackle the down-to-earth side ourselves. Yup, it’s the BUILDblog vocab list for down to earth architects who want to get things built. Here’s a handful that you’ll need:

sparky (spär-kē), n. the jobsite electrician.

skillsaw (skil-‘sȯ), n. a portable circular saw originally produced by the Skil brand and commonly used to cut framing lumber in the field. Useful for cutting straight lines.

sawzall (sȯz-ȯl), n. a type of saw in which the cutting action is achieved through a push and pull reciprocating motion of the blade. Blades can be switched out to allow cutting of wood, steel and plastics. Useful for notching or cutting curves.

sister (sis-tər), v. to attach one joist to another, usually side by side, thereby strengthening the overall assembly. The attachment is typically achieved with nails or screws.

plumb-bob (pləm- bäb), n. a weight, usually with a pointed tip on the bottom that is suspended from a string and used as a vertical reference line.

pex (peks), n. short for cross-linked polyethylene, this piping material is flexible, durable under temperature extremes and highly resistive to chemical attack. It is used for hot and cold water plumbing systems and hydronic radiant heating systems. Traditional copper plumbing is being replaced by pex as the standard for plumbing in many applications.

smurf-tube (smərf-tüb), n. a blue colored flexible conduit used to encase low voltage electrical runs such as speaker wires and data cable. Typical diameters are ½” and ¾”.

j-box (jā-bäks), n. short for junction box, this metal or plastic container for electrical connections conceals electrical connections from sight and deters tampering. They sometimes include terminals for joining wires and typically include an access panel.

cattywompus (ka-tē-wumpəs), adj. crooked; lopsided or askew.

plumb stick (pləm-stik), n. a common framing level.

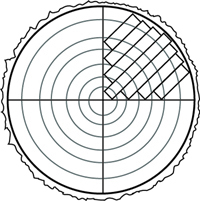

plain sawn (plān-sȯn), vt. the most common and widely used method of sawing lumber. Plain sawn lumber is produced by making the first cut on a tangent to the circumference of the log. Each additional cut is then made parallel to one before. This method produces the widest possible boards with the least amount of log waste. Therefore, it is more economical in comparison to the other sawing techniques utilized within the industry. Plain sawn lumber offers a distinct cathedral effect to the grain on the face of the boards. Also commonly referred to as “flat sawn”.

quarter sawn (kwȯ(r)-tər-sȯn), vt. produced by first quartering the log followed by sawing it perpendicular to the annual growth rings. This particular method of sawing produces a nice straight grain appearance on the face of the board. Quarter sawn lumber creates more log waste and therefore the end result of narrower boards in relation the plain sawn technique.

comments button (kä-‘ments- bə-tən), n. it’s that button at the bottom of the page that allows you to share your thoughts and stay in the game.

Keep both feet on the ground and have a great weekend.

To get the play-by-play action and behind the scenes look at the BUILDblog follow us on Twitter.