[Romick Residence by Stephen Gassman, 1972, photo by Julius Shulman]

Julius Shulman, the master photographer of mid-century modern architecture, passed away on July 15th at the age of 98. He is revered not only for his photography but also for the important part he played in modern architecture. Whether it was foresight or just pure passion for the work, Shulman probably did more for mid-century modern architecture than most architects of the time. And as we’ve witnessed, the photograph is often around much longer than the building. A well-composed, intelligently promoted photograph has the ability to be a catalyst much more so than stationary architecture. In this case, his work is not only a means for modern design, but as to how we live and work, how we behave and think, what we surround ourselves with and what we strive for. Shulman’s work played a brilliant role in the evolution of society.

As architects and amateur photographers here at BUILD, we look to Shulman not only for inspiration but also for technical know-how about the photograph. We’ll show some of his gorgeous work in today’s post and also break down the compositions into 10 key ingredients; each of which influence our own work. As per usual, let us know what you extract out of the images.

1. Exploration: The projects in Shulman’s work are presented as if you’ve unexpectedly come across them while taking a walk. The blurred vegetation in the foreground implies that you’ve just discovered something intimate and special.

[Zimmerman Residence by Craig Ellwood, 1953, photo by Julius Shulman]

The interior photos are presented as explorations for the viewer. There is always depth to the photo, an open door to the outside beyond, something around the corner, a pool of water in the background. The photo leaves you curious about the project and hungry for more information.

[Pereira Residence by Pereira & Associates, 1962, photo by Julius Shulman]

2. Perspective: Although the structures he captured on film are mostly orthogonal with long flat roofs, Shulman almost always employed perspective in his images to give the architecture direction and energy. While vertical lines are kept vertical (with help from perspective correcting lenses) the horizontal elements like the trellises, so common in mid-century modern architecture, become dynamic objects, extending out of the photograph.

[Dudley Murphy Residence by Griswold Raetze, 1946, photo by Julius Shulman]

[Fulton Residence by Rodney Walker, 1948, photo by Julius Shulman]

3. Framing: Very rarely is the entire room captured in the photograph and the image is typically framed using objects within the picture itself. Shulman would typically make use of vegetation or furniture to compose a frame within the photo.

[Garred Residence by Milton Caughey and Clinton Ternstrom, 1950, photo by Julius Shulman]

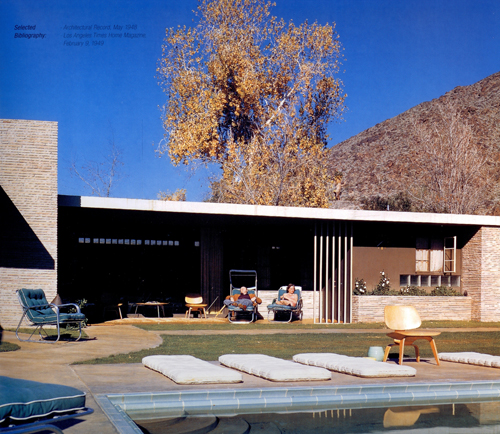

4. Bookending: The monolithic volumes so common in mid-century modernism are used as bookends to the photo. The concept is similar to ‘framing’ but usually employed on exterior shots that captured more of the architecture.

[Town and Desert Apartments by Herbert W. Burns, 1947, photo by Julius Shulman]

5. Layering: Because depth of field is so important in Shulman’s images, the camera is typically positioned to capture several planes at once. In the photo below the tree frames the image of a trellis casting a shadow onto the table and the ground – the multiple layers make for a deep, rich image.

[Smith Residence by Whitney Smith, 1953, photo by Julius Shulman]

6. Long Exposures: Opening up the exposure of the camera is often used with nature in Shulman’s photographs. Elements like water become misty and smooth, fire becomes a warm glow, the fluttering leaves of a tree branch hint at the presence of wind.

[Daniel House by Gregory Ain, George Argon and Visscher Boyd, 1939, photo by Julius Shulman]

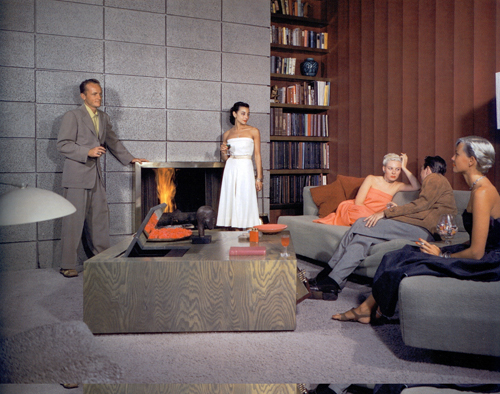

7. Static People: Interestingly enough, the long exposure shots discussed above are rarely applied to people. Although the technology was certainly available to capture the movement of humans, the people in Shulman’s images seem staged and static. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, and it was clearly intentional. Our take is that the people were deliberately photographed to look stationary and it was the architecture that took on the dynamic role in the images.

[Spencer Residence by Richard O. Spencer, 1950, photo by Julius Shulman]

8. Props: If there is a fireplace in the photo there is typically fire. It brings warmth and light to the composition and with the long exposures it adds a layer of movement to the shot. Drinks ready to be consumed give the feeling of life and motion, sometimes without even showing people in the shot.

9. Crisp Shadows: The shadows are so clean and defined that they become another layer within the photograph. Shadows are often used to enhance a specific aspect of the structure; the shadows in the image below allow the open joists of the trellis to pop out from the gray sky background.

[Laszlo Residence by Paul Laszlo, 1948, photo by Julius Shulman]

10. Red: In most of Shulman’s color images red makes a small but significant cameo appearance. Usually in the form of furniture or furnishings, a bright red element is added to the composition.

[Leeds Residence by Joseph Johnson, 1958, photo by Julius Shulman]

We’ll end with one of the few projects Shulman shot in the northwest: the Runions Residence designed by Ralph Anderson in 1969. Cheers and get out there with your camera.

[Photo by Julius Shulman]

All images from the book: Julius Shulman, Modernism Rediscovered, text by Pierluigi Serraino, Taschen.