[Deitingen Service Station, Solothurn Switzerland, 1968]

With the discussion of efficient and sustainable design more important than ever in architecture, we thought it would be relevant to brush-up on the work of Heinz Isler. Born in 1926, the Swiss artist-designer-engineer developed his concepts and methods for thin shell concrete structures in the 1950’s, came to prominence with his constructions in the 1960’s and continued developing his ideas and built-forms into the 1990’s.

[Norwich Sports Village Hotel, Norwich England, 1991, Architect: J.A. Copeland]

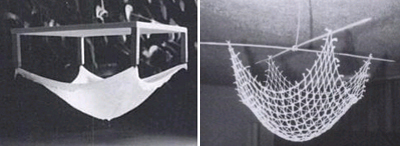

An anomaly of the engineering world, he directed his efforts away from the mathematics of engineering and focused on the physical model. This study into physical modeling put emphasis on form and stability. The goal to create structures of high efficiency with the lowest possible environmental impact led Isler to explore 3 types of formwork: molded earth, inflated rubber membranes, and draped fabrics.

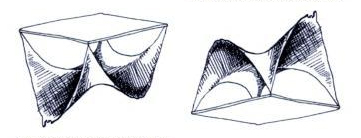

The studies with fabric are most interesting to us because of the relationship between the fabric’s capacity for tension and the concrete’s capacity for compression. The small scale models, made from draped fabric, define the most effective structural curvatures, however the material in this model is primarily in tension –something fabric is very good at. In order to apply this same curvature to concrete, the model is “frozen” with epoxy resins and then flipped 180 degrees, thereby putting the material into compression – a strong characteristic of concrete. This geometry can be scaled up to whatever size necessary. Such simple and elegant relationships between geometry and material properties are fascinating to us.

Adding to the overall efficiency of the built-work, Isler often used fiberboard as the construction formwork, a material known for its insulation qualities. This not only helps keep the heat in but regulates the temperature of the concrete inside and outside the shell, subsequently controlling the expansion and contraction of the concrete.

[Indoor Tennis Center, Heimberg Switzerland]

Complimenting the conceptual and structural importance of Isler’s studies in thin shell concrete structures is a poetry rarely achieved in engineering and architecture. For us architects, it’s a reminder of the important relationship between built-form and the geometries inherent in nature. All too often, it seems us architects strive to force materials into built-forms which are contradictory to their natural properties and to physics in general. As Isler’s studies demonstrate, the solutions to built-form are often times simple and obvious; the answers are already coded into the material itself.

[Bruhl Sports Center,1982, Solothurn Switzerland, Architect: J.A. Copeland]

[Wyss Garden Center, 1961, Solothurn, Switzerland]

[La Tene Tennis Center, Neuchatel Switzerland, 1983, Architect: J.A. Copeland]

[Truffaut Villeparesis, Lle De France, France, 1977]

[Cafe-Restaurant Wiesentalstrasse, Grisons Switzerland, 1975, Architect: Th Domenig]

[Deitingen Service Station, Solothurn Switzerland, 1968]

[Ecola Nationale de Ski et d’Alpinisme (ENSA), Charmonix-Mont-Blanc, 1974, Architect: Robert Tallibert]

[Sicli Company Building, 1970, Geneva]

“The model has an answer to (nearly) everything” – Heinz Isler

[The Engineer’s Contribution to Contemporary Architecture HEINZ ISLER by John Chilton, Riba Publications]

Resources:

The Engineer’s Contribution to Contemporary Architecture HEINZ ISLER by John Chilton, Riba Publications

The Art of Structural Design, A Swiss Legacy, Princeton University Art Museum, David P. Billington

Conceptual Structural Design, Bridging the gap between architects and engineers by O. Popovic Larsen & A. Tyas

All photos by Yoshito Isono, Structurae